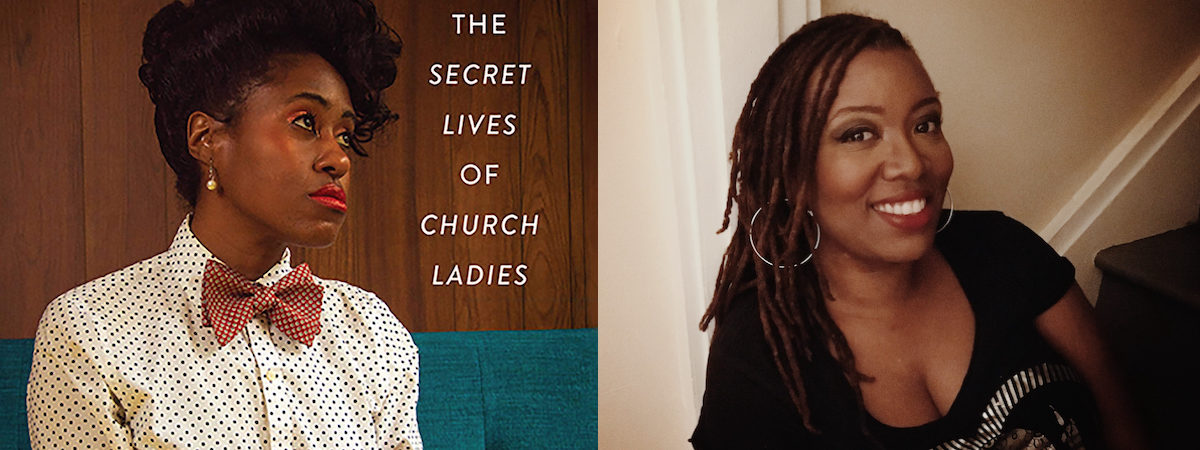

A Conversation with Deesha Philyaw

Deesha Philyaw’s debut fiction collection The Secret Lives of Church Ladiescracks open the dam on southern Black women’s rawest and often-denied wishes. In both its absence and oppression, the Black southern church offers a tainted backdrop to the lives presented in these nine stories, all springing forth from what the author calls a single kernel dissatisfaction.

What if?looms over fifteen and forty year olds alike when they explore the complexities of human relationships—most notably those with their mothers and lovers—and the peculiar utility of fantasy and revenge. These are lessons that can never be (un-)learned too early or too late, as the book’s elders struggle to achieve their own versions of a potent self-love. In The Secret Lives of Church Ladies,all of this is tackled outside the mahogany pews and with characters who merely orbit the “church ladies” of our imaginations and lived experiences.

Deesha Philyaw and I dove into a COVID-19 catch-up via Zoom in early July 2020. Originally scheduled for release September 1, The Secret Lives of Church Ladiesis available now via West Virginia University Press.

—Rose Gorman, Contributing Editor

Rose Gorman: How are you? How are you doing during this pandemic?

Deesha Philyaw: I’ll say, ‘okay, all things considered.’ And that’s how I’ve been emailing people: ‘I hope you’re doing well, all things considered’ because good things have been happening for me in the midst of this pandemic, with all the stuff with my book, the positive reception. I’m grateful for that.

So, it’s been a kind of mixed bag, plus being in isolation. I’m by myself—literally by myself—most of the time because my youngest daughter isn’t here. And I’m taking this seriously. I don’t go out. I might go for walks and stuff like that, but I really am sheltering in place. That’s challenging, but at the same time, circumstances have also brought me closer to friends. We’re being more intentional about spending time together.

People complain about the Zoom stuff, but I’m enjoying it. I’ve been having a regular Caftan and Cocktails get-together with some friends. Some of us are having Zoom writing time together—late night, early morning—things we weren’t doing before. So, having to be intentional about connection is actually a good thing. But, of course, the fear of losing people you love and getting sick and this reminder of the stranglehold that white supremacy still has on all of us.

It’s interesting that I’m having these parallel experiences. It’s the scariest time I’ve ever experienced and also a time of great joy and connection with people I care about and people around the globe.

RG: That’s real. Pittsburgh is having a bit of surge right now, right? Or am I making that up?

DP: No, you’re right. After being on the decline, they did what you’re not supposed to do: When your numbers are declining, the right thing to do is keep doing what you’ve been doing to get the numbers down. But immediately, bars were opening and people were down partying by the river and nobody wants to wear masks. So now there’s that spike. The irony was that people wanted to blame it on the protesters, but the protesters are wearing masks.

RG: And I love that.

DP: Right. But people are like, ‘You’re not going to tell me what to do. You’re not going to tell me to wear a mask, and you’re not going to tell me that I have to respect Black life.’ So, there’s a lot of people throwing these tantrums that have fatal consequences for other people. I thought things were getting better here, but then there’s this spike. One thing it’s shown us is how dependent we are on other people who don’t care about anyone but themselves. That’s especially terrifying.

RG: Who do you think you’re dependent on?

DP: Fucking complete strangers who just decide that ‘I’m gonna wear a mask, and I’m gonna put it under my nose. Or I’m gonna wear it around my neck like a necklace.’ People who clearly aren’t taking this seriously. We’ve always known that our fate was intertwined with other people, but this has hit home in a way that I’ve never seen in my lifetime. That’s unsettling. But you can curl up in a ball and feel terror. Or you can curl up in a ball, feel terror and occasionally come out and hang with your friends, and get groceries, and cook food.

RG: That’s true. I talk about ‘the universe’—especially when I talk about religion—and I say, ‘As long as you know you’re not the center of the universe, then you’re fine.’ But there are a lot of people who don’t believe that. I gotta say, with the quarantine, I’ve been able to take advantage of all the writing advice you’ve given me.

DP: Yay!

RG: I’m using it as an excuse to quit all my jobs except one. I’m actually writing, and all our conversations have been really helpful. That’s been an upside.

DP: It made everybody slow down. It really really did.

RG: That’s the way it should be. Things weren’t that great to begin with.

DP: How many times do we say, ‘If I could just press pause…’

RG: Yeah!

DP: And this is a ‘pause’ for that ass! Right?

RG: I will say: I am sorry the [Black Writer] Family Reunion didn’t happen this summer. What are the plans for that?

DP: It may do something virtual, but there’s also a lot of uncertainty around funding now for big events.

RG: Yeah, jobs went away…

DP: Yeah.

RG: I’m still holding out hope. When it comes to The Secret Lives of Church Ladies,it’s nice to see this out in the world.

DP: Yay! I feel that way too.

RG: I remember when you were talking about it and trying to get your revisions done, and now we have this product—I’m giddy! It brought a sense of comfort reading it these past few weeks. I feel like I know all these characters from some point in my life.

DP: That’s wonderful.

RG: Some of these pieces were published previously and then brought together in this collection. Why did you bring all these characters together? What made you think The Secret Lives of Church Ladiesneeded to be in the world?

DP: I can’t take credit for that. It was my agent’s idea. I was actually working on a novel, and the main character was the first lady of a church. I’d been working on this novel since 2007 and had co-authored a whole other book since then.

RG: In a whole other genre.

DP: Yeah, non-fiction. I took a whole other detour, came back and was picking around with the novel and trying different things. I was always in communication with my agent about it. She would always ask me about it.

Then I started writing short stories and started reading them at events here locally [in Pittsburgh]. My agent came to my events, and after one of them said ‘Maybe while you’re taking a break from the novel, you can make a collection of these stories you’re writing instead.’

I hadn’t thought about being really intentional about it. Church ladies just organically show up in my writing, or people I call “church lady adjacent”—meaning, if they’re not a church lady, someone in their life who’s influential is a church lady. After she suggested that, I got really intentional about making stories where that was a factor. That was the kernel. There had to be a church lady. The character had to be a church lady or church lady adjacent.

She said, ‘Once you get three of these published, that’s enough to start shopping a partial manuscript.’ So, I got to work, and by the time we started shopping the partial manuscript, it included six stories—three had been published, three had not—and the book sold on the strength of that. I decided I didn’t like one of the stories, so I had five stories.

West Virginia University Press is my publisher. They gave me a word count, so I had to get to 35,000 word. I didn’t know how many stories that was going to be. So I just started writing. I got to 35,000 words, and that ended up being four new stories.

RG: Wow.

DP: I had been working on different stories for a while, so it was a matter of deciding which stories was I most interested in. I asked a couple of friends. I gave them a premise or a line or something, and asked ‘Which ones are you most interested in?’ Ultimately, I had to be interested in them, but my friends helped me narrow down which ones I was going to focus on. I had my top five and was just going to start writing and see. I got through three stories and got a word count. I had one more story left. I looked at the two stories I had left, and I wasn’t really excited about either one of them. Clearly, I’m fickle. I started out excited about them, and by the end, I said, ‘Eh…not really into either of these.’

But of one them, I stayed with the premise, and it was what became “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands.” That one started out as just about the woman. She’s a serial mistress. Initially, I thought, ‘Boring. That’s been done.’ I just was not interested in that anymore.

Around the same time on social media, there were these memes going around. It was the wives versus the side chicks. The wives would say, ‘I got his 401K’ and the side chick would be like, ‘I love her husband.’ (laughs)

RG: Memes are great writing prompts.

DP: Yes! I had a friend of mine say that there needed to be a side chick academy so people could learn that you can’t be wearing a shirt that says, ‘I ♥ Her Husband.’ The serious thing was that it always pitted the women against each other, and the guy is off doing whatever. The women are always fighting with each other.

So, I thought, what if the main character was the mistress, and she had the upper hand? What if she created the rules of engagement with her? That opening scene, when she’s giving instructions for what to do when you arrive, that was what I started with and then I built the rest of the instructional manual around that—I had fun with it!

RG: It was fun to read! I’m a sucker for form.

DP: Oh, I love it too.

RG: That’s what I love about McSweeney’s. You get all these experimental pieces. Did “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands” come before “Peach Cobbler”?

DP: No, that was the last thing I wrote. But I didn’t want it to be the last thing in the collection.

RG: Why not?

DP: It’s such a provocative piece, it’s not the kind of deep sigh that I felt would be right for the end of the collection. “When Eddie Levert Comes” is that deep sigh. It’s a quieter story.

“Peach Cobbler” is next-to-last in the collection. I wrote it two or three years ago. It was one of the earlier pieces. It got rejected from so many different publications, I lost track at a certain point. Let that be a lesson to all the writers. I put that story in the book, but nobody wanted it. I heard it was too long. They couldn’t understand why a mother would act that way. People just couldn’t relate to the mother character.

RG: What type of publication did that come from?

DP: (laughing) It got rejected a lot by some fine, established literary magazines that I admire and aspire to. I won’t name names but different reviews and journals. And that’s fair. I’ve learned to not be discouraged by it. It’s subjective. The story does resonate with people. But it didn’t resonate with those particular people. And that’s okay.

RG: Everything is not for everyone, and that’s what I love about this book. There are things I read and cackled out loud. I’d read my partner passages—she’s white—and she’d respond, ‘Okay…’ And I go, ‘Clearly, this ain’t for you.’

DP: (laughing) Some interesting Negro humor.

RG: And I think that’s beautiful, though. It’s okay to have our F.U.B.U. moment.

DP: Absolutely. Truly. Shout out to my editor [Sara Georgi] at West Virginia University Press. She had a lot of faith in me, trusting my voice and the character’s voices and the language. She is a white woman, and so some of it was unfamiliar. We were doing the last bit of edits, and in “Jael” the grandmother says, ‘I stay prayed up.’ She was changing the tenses, and I said, ‘No no no. ‘Stay prayed up.’’

It was such a respectful process. She just wanted to make sure it got into the world clean and clear. But there were certain nuances and cultural things, and it was a great collaboration with her.

RG: How did you negotiate those moments in which you had to interpret your words? I’m thinking about this especially in light of the dialogue happening around writers of color—particularly Black writers—sharing their experiences in predominantly white newsrooms and in the publishing industry.

DP: It was smooth sailing. It started from a place of respect and trust—and not just for me as a writer but me as a Black southern woman. I know that world, and am an authority on that world. I was respected as such. They also had respect for the stories and the characters. Sara really loved the book and loved the characters.

Sometimes, in addition to the general white supremacy that we’re up against, it’s just laziness when editors don’t handle us and our work with respect. But [Sara] did her homework. In the publishing experience, there’s a style guide, but then they create a style guide for your book, with words that may be uncommon. She had to do that research. So, there were very few things that she had to come back to me about. ‘Stay prayed up’ was one, and it’s clear it’s tricky: It’s messing with tenses and things like that, but she asked it as a question and not ‘I think it should be…’. It was never a moment of that.

I got so excited when I saw the style guide. They sent it back to me with the final manuscript to proof, and I posted it on Facebook because I thought it was fun. The style guide itself tells the story. It’s super Black. It’s all of these terms and expressions that are not for the average white person or the average reader. These were not words that were considered technically common. To make sure they were spelled the same and punctuated the same throughout, the style guide was created. To make the style guide, [Sara] had to have done her homework on them. She created a reference guide based on my stories, and I was so hyped about that. The collaboration was seamless and respectful.

(laughing) She did say, ‘One thing I couldn’t find was whether or not a dozen medium crabs would cost six dollars in Jacksonville, FL in the mid-Eighties.’ She said, ‘I really tried. So, are you sure?’ And I said, ‘I’m sure that is what it was.’ Seriously, that was it.

Meanwhile, I know other writers that have had experiences where they did have to do a lot of translating and interpreting. That would have made me feel othered. And I never felt othered. This is the book. These are the characters. This is their world, and you’re invited into it. This is how they speak, and this is how they see the world. There was a baseline respect for that.

When I talk about white supremacy, there’s a hand-wringing over ‘Will white people understand this?’ Yes, you want to be clear, but if you’re entering a world that is unfamiliar to you as a reader, the writer’s job is to make you want to enter that world. But as readers, we have to want to get involved too. If I’m reading about a world that I’m not familiar with, I don’t want somebody to explain everything to me. I want to figure some things out. We all learned how to use context clues. I don’t want that layer of interpretation to get between me and that world and me and those characters. [In my publishing process] I never got the impression that it was ‘Help us help white people understand this.’ And guess what? White people don’t seem to be confused.

To your point, some of the things that are more insider baseball may be lost, but on the bigger themes and positive things I’ve heard from white readers, they’ve enjoyed it. Nobody has said, ‘Oh my god. I was so confused. I don’t know what they were talking about.’ No one said that.

RG: That speaks to the universality of what the characters are going through. Why are you so obsessed with church ladies—enough to want to write a novel about them. That’s quite a commitment.

DP: (Laughing) I’m going to give you an answer that occurred to me recently because I’ve been asked this before. My short answer: I grew up in the church from a very young age, sat through a lot of sermons and a lot of Sunday school classes, a lot of Bible study, into my thirties. Church ladies really made an impression on me as a teenager. Women inside the church, along with women who were outside of the church but still in relationship with the church.

They say, ‘I’m gonna go to church when I get right.’ That kind of thing. They fascinated me. And then women inside of the church fascinated me, as well. We don’t know it at the time, but as teenagers or adolescents, we’re trying to figure out, ‘Well, what kind of woman am I gonna be?’ These were my early models of womanhood, and they shaped my understanding of what it meant to be good, what it meant to be a good girl,and then into love relationships. I’m someone who married early. I was twenty-two years old when I got married.

RG: You were a baby.

DP: (laughing) I was a baby. So, I wasn’t conscious of it at first, but the new part of my answer: I think I was working stuff out, and I have been since the early 2000’s about who you’re supposed to be in the world and what is supposed to satisfy you, and how you present to the world versus what you really want. Those things can be at odds. So, my first attempt at a novel was a disaster. The second one I think is going to have legs—I mean, it should after thirteen years!

Both of them had women that were church ladies who were dissatisfied, and I think that—I know that was me. I wasn’t a pastor’s wife or anything like that, and certainly we make things more dramatic in fiction than they are in real life. But you’re living a life that you’ve been told is what you should aspire to and what should make you happy. But what if it doesn’t? In hindsight, I realize that I was channeling my own questions and dissatisfaction through these characters who were dissatisfied and who were finding themselves at odds at what it meant to be good or someone else’s expectations of them.

The church is almost peripheral. You don’t have to be in church or have a Bible thumper to have the influence of the Black church be all over your life. Even in absentia, you can react to something that’s very powerful. So, it stuck with me. When I’d write out of my imagination or out of my need at those times, the stories I wanted to tell, I confronted things in those narratives that I was hesitant to do so in my own life. By 2007, I was divorced, but even though I was out of an early [and] long marriage—that experience of walking away from something that everyone said should fulfill you, should sustain you, but what if it doesn’t? I was still playing with that question through fiction rather than through personal essay.

RG: Fiction’s more fun.

DP: Yeah, oh, so much! You start with that kernel of it and then look at all the different directions that you can go. With this collection I went nine different directions but from that same kernel of dissatisfaction.

RG: (laughing) When it came to an exploration of the church ladies, it was an exploration of the lives that they descended upon from that dissatisfaction. I appreciated those peeks at what it’s like to be touched by someone else’s spiritual life in a significant way—especially when you’re so young. I would almost call this collection ‘coming of age’ given what we see of mother/daughter relationships.

DP: (laughing) So, about that: I was done with the collection, when I realized ‘Oh, This is about mothers and daughters.’

RG: It’s a lot about mothers and daughters!

DP: Yeah, clearly, I’m working some other stuff out too.

RG: We have “Not-Daniel” and “When Eddie Levert Comes” where we have these daughters in the role of caregiver to their aging mothers. In thinking about the circle of life—and the life of this book—daughters tend to be the ones called upon to play this role. Was that something you meant to dig into throughout the collection?

DP: That was my subconscious. (laughs) I had a very challenging relationship with my mother from the time I was young. When she was forty-nine, and I was thirty-one, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Four years later, she died. So, I’ve written intentionally and consciously a little bit, but that is probably, hands-down, the defining relationship of my life. So, I think it’s going to always show up.

Interestingly, though, in the novel I’m working on, I kill her mother off. There are circumstances around her mother’s death that still impact her, obviously, but I don’t think the novel is going to be a mother-daughter book the way that this collection was because there’s some other stuff going on. I’ve written enough of that book to know that it’s not a mother-daughter book.

But in the collection, I think I was working some stuff out, even down to “When Eddie Levert Comes.” The O’Jays were my mother’s favorite group, and there is a picture. My mother went to a O’Jays concert and took pictures with them backstage, but I think the picture is with her and all of them, and not just Eddie the way it is in the story. That [story] is probably the closest to paying homage, but that mother was nothing like my mother was. So, there are some parts of this that are definitely autobiographical. I already prepared myself for people to ask me certain things. I mean, can I have an imagination? This book is ninety percent fiction. There are some characters that have elements of my mother in them, but “Eddie Levert” is direct homage to my mom because she loved Eddie Levert so much and loved the O’Jays. But I didn’t have that caretaking experience with my mother. She went into hospice, was there for six weeks, and she was much younger than the mama in the story. We did have a difficult relationship, like those characters, but ours was difficult in a different way.

RG: The daughters reflect on their relationships with their mothers a lot. “Peach Cobbler” and “Instructions” speak to each other in this way. What were some of the lessons you took from your mother when it came to love, relationships, and self-worth?

DP: My mother was a giver. She put herself last. So, I learned what not to do. I’m a giver too, but I’m not a martyr. I refuse to act like I don’t have needs and be this vessel that pours into everybody else. That’s what my mother did.

RG: There’s no glory in struggle.

DP: Yeah, and asking for and expecting very little from people. That didn’t serve her, and it didn’t serve me when I used to be that way. That’s something I definitely had to unlearn. We should take up space, and we should ask for things, and we should expect reciprocity. As a friend of mine said about reciprocity in relationships, ‘I don’t think reciprocity captures it,’ he said. ‘It’s symbiosis.’ That’s what you want in the relationship. Either way, there’s balance. What she showed me was imbalance. If there’s anything I’m sad about it’s that she didn’t have that reciprocity she deserved—that we all deserve.

By that same token, there was an incredible generosity of spirit that my mother had. She would host and take care of everybody and cook for everybody and think about the little details that made people feel special. If it weren’t for that, I’d be a much more selfish person than I am. And she dressed up and thought things should be beautiful, to the extent where I care about beautiful things. That is from my mother, and I fought it.

She was a glamour girl, and I was bookish. In the late-seventies or early-eighties, my mom would go to the grocery store fully made up in daisy dukes, heels, and her shirt tied at her waist. I’d trail behind her embarrassed. She was drop-dead gorgeous, and I rebelled against that for the longest time. I didn’t want to wear make-up, I didn’t want to draw any attention to myself. My style was very plain. It probably wasn’t until right before she died that I glammed up a little bit. I was doing it because I wanted to and not because I felt this pressure of being her daughter and having to look a certain way. She was beautiful.

RG: It makes me think of Oda Mae in Ghost and how Sam would overtake her body, like your mom overtook yours.

DP: Yes! She did. My mother loved jewelry—she loved gold. And she’d wear orange with a gold belt. Listen, you could not tell her anything. So, I did not wear gold. I always wear silver. I’m wearing silver now. But last year, for some reason, I said, ‘I’m gonna get some gold jewelry.’ I thought about her in those moments and thought, ‘I can enjoy all of this.’ I don’t have to keep trying to define myself against this mold she was trying to force me into. I can enjoy gold jewelry now and all the lipstick.

RG: Were they door knockers?

DP: (laughs) No, they weren’t. But I might have to rock some door knockers. Right now my hair is up. Because I have locs, you really do need some big earrings. Post-pandemic, when I actually have somewhere to go, it’s over for y’all. When I’ve got to get clean, it’s gonna be big and bold because I’ve got stuff to do.

The pandemic was a reminder that we don’t have time. You don’t know if the last time you see somebody is the last time. Or if the last time you have sex, is that going to be last time? (laughs) I’ll probably be a little reckless once the world opens back up for a little while.

RG: “How to Make Love to a Physicist” is all about time to me. The protagonist puts off so much. I know her relationship is long distance, but jeez.

DP: Because she didn’t think she deserved good things. You know? She got on my nerves.

RG: Earlier you were talking about pieces that you just got tired of. Were there any characters that you got tired of talking to or working on?

DP: Yeah. In “Dear Sister” it was Renee, the prim and proper one. She’s the one that I would say, ‘Girl, you just don’t have time.’ She wasted time with their father, trying to get him to be the father she needed him to be. Instead, she was his maid. And now, she’s policing her sisters. She frustrated me in the sense that she and I would never be friends. I could probably be friends with all of the other sisters. (laughs)

RG: Tasheta was fun.

DP: Yes, she was a lot fun—a lot of fun. And just embarrassing.

RG: (laughing) She showed up to the funeral in a backless dress and some clear heels, and someone had to give her a blazer to put on.

RG: When it comes to men in “Dear Sister” and “Jael” the women seem to have their ‘Bernadine walking away from the fire’ moments in the book. I don’t know how you feel about comparisons, but “Jael” reminded me of something Toni Morrison would’ve written.

DP: Oh gosh—thank you.

RG: Like, when it came to the authenticity of the tongue and the richness of the names of characters. I forgot how much is in the Bible—names other than Matthew or Daniel—there are some really interesting names in the Bible. There’s a lot in this story. How did it come about?

DP: It’s been at least five years, but I don’t know how I first heard the story of “YAH-ell” in the Bible. I pronounce it “JAH-ell” in the story because that’s how we would say her name. If there was a Black girl named Jael, we’d pronounce it “JAH-ell” or “jail”. In Hebrew it’s “YAH-ell”.

I was fascinated by that story. She invites this man into her home and nails his head to the floor after he got the Itis when she gave him heavy cream. The imagery of him sleeping and her taking a nail and driving it into his head and nailing him to the floor, there was something so visceral and grotesque about that. I was just fascinated by that.

RG: Why did she do that?

DP: Her husband was a bigwig in the Israeli army, and he was a general in the army of one of Israel’s enemies. He came to her door asking for water. I mean, how did he think this was going to end? He really underestimated her. He asked for water, and she gave him cream. It made him sleepy, and when he fell asleep, she killed him. Think of all the ways she could’ve killed him. That was personal.

RG: That took work.

DP: She was serious. So, I started thinking about a fourteen-year-old Black girl who’s named for this character who killed someone. What would she be like? So, it started with a journal entry, and the chronology is almost true to the draft. I started with the grandmother saying, ‘I’m worried about this girl. There’s something in her journal…’ Then, Morris Day came up, and I started thinking about the predators in the neighborhood I grew up in. So, her deciding to kill him just sort of happened in the process. I worked on this story for probably two years, but I didn’t know what she was going to do going into it. It just made sense that, as she and her friend started to drift apart, and give her namesake, she was going to kill him. And then it was easy.

RG: There’s so much there. If you were to chop the story in half and only read from her grandmother’s perspective or Jael’s, there’s so much to unpack. Even the grandmother’s denial of Jael’s queerness—which runs throughout the book.

DP: And I don’t want anyone to feel like I overstepped. I think about a couple of things: I think Kiese [Laymon] says something in Heavy. The way he writes about childhood, so many of us were queer, and it speaks to the notion of fluidity. It’s all forming. We don’t always lose that in adulthood, but as someone who’s never identified as queer, I thought, ‘Do I have permission?’ But the characters were who they were. I’ve had lots of people read the stories, and no one has said, ‘You’re pandering’ or ‘That’s a stereotype’ I would be sensitive to something like that, but that all happened organically.

RG: Did you bring on sensitivity readers?

DP: No, I figured if I misstepped, then somebody would tell me. I have enough friends from all kinds of backgrounds who read the book, but I never asked somebody to be a sensitivity reader on these things because some of these were my experiences or some of these were experiences of people I was close to or who confided in me. So, I thought I knew enough. But I’m always still mindful of when white people say, ‘Well, I interviewed some black people…’ That’s not what happened at all.

When I talk to my friends who are bisexual, they talk about this invisibility. Who gets to claim certain labels? I’ve been married to men twice, but what do I get to call myself if I’ve had other experiences? I didn’t really think about queerness, like I didn’t think about mother-daughter. It was just who those characters were.

RG: How did you know they were queer?

DP: With “Eula,” those are two women—even Caroletta—who would never even identify as queer. It was more, ‘This is a thing we do.’ With Jael, identity and sexuality are still forming at that age. Jael struck me as ahead of her time. She just knew she was in love with the preacher’s wife and had feelings for her best friend. Those were things that I discovered along the way.

In “Snowfall” that’s the one story where two people identify as lesbians. That story came about when my friend Abeer [Y. Hoque], who is a Bangladeshi-American born in Nigeria, had her book Olive Witch coming out. She asked me to read [at the book launch]. We were the opening act, me and Tuhin Das, who is a Bangladeshi poet in exile living here in Pittsburgh. His poetry and her memoir were all about place and displacement, and I’m writing about church ladies in the South. I didn’t have anything on hand, so I thought, ‘I’ve got to write something.’

This was several years ago. It was really cold and there was a hard freeze the weekend I wrote it, and I thought, ‘I feel displaced here in Pittsburgh.’ I’m from the South, and I’ve lived here longer than I’ve lived in the South, but I still have never gotten used to the cold. So, I thought about that kind of displacement. Then I thought about this idea ‘home.’ While I miss Florida when I’m here in the winter, I don’t necessarily want to go back to Florida to live.

I could see the two characters in the story clearing the snow. In the first draft of the book, they were both outside at the same time. Their reason for being there and not going home and trying to understand this voluntary displacement because they were queer. I just saw these two women clearing the snow first, and initially I didn’t think of them as a couple. But they were going back and forth, and I thought, ‘Oh, they’re a couple.’

RG: Going back to “Eula”, how did the piece change between the version published by Apogee and the one included in the collection? How did your feelings change towards the story?

DP: I don’t think it changed a whole lot. There’s a scene I’m thinking of that I expanded, but I think I expanded it for Apogee. I think it was a lot more copy editing that happened, but not much else changed. If memory serves, I think it’s the most sexually explicit story in the collection, maybe.

Believe it or not, I can still be self-conscious about those things. I remain self-conscious about that one being sexually explicit. It’s too long for me to read at a reading, which is good because I don’t think I could get through it. (laughs) “Not-Daniel” is pretty explicit too.

RG: Yeah, it’s nice and quick, in more ways than one.

DP: (laughing) Yeah. I think “Eula” was published by Apogee in 2016. It had been a long time since I’d published fiction. It’s a different gaze on your work than non-fiction. Here I come with “Eula” and it’s sex from start to finish. And I was self-conscious about that. I always knew it should be first in the collection. I was like, ‘Listen, let’s just jump right in.’ (laughs)

RG: While we’re here, was that the first story you wrote?

DP: “Eula” was the first one I wrote, and it was the first one that was published. I thought, ‘Well, it should be the first one in the collection.’ It’s an attention-grabber. You’re either going to stick with me after that or you’re not. I certainly had more fun writing some of the other stories.

People talk about that story. I have a friend who was working on his thesis and talks about “Eula” in his thesis, something about Black masculinity. Wednesday Martin wrote this book called Untrue, about female sexuality and promiscuity, and she has a whole chapter devoted to Black women and women of color. She opens the chapter with me and my work and quotes from “Eula.” People really like that story.

RG: It’s interesting that you’d think it’s blush-worthy. How would you feel about teenagers reading this collection?

DP: I think it would be great. Someone has asked if they thought it would be appropriate, and I said, ‘Yes. However, I will send you an advance copy so you can preview it and decide for yourself.’ And she decided her 11th and 12th graders could handle it. I don’t think it’s pornographic. I think teenagers should read whatever they want to read as long as it’s not harmful to them. And I don’t think there’s anything that’s harmful or disturbing. I would hope that it would be affirming for them.

RG: What do you think they’d get from reading the collection?

DP: Well, once the titillation was over, I’d hope the girls especially would identify with the women who are tortured by their own desires and won’t allow themselves to want what they want and who basically live in a box of either someone else’s making or boxed in by their own fear. It’s like a lesson: This is how the story ends. If you keep playing small now, this is where you’re going to be when you’re forty, in damn hotel rooms. (laughing) Go out. Be who you’re gonna be. Love who you’re gonna love. Take care of yourself. Be careful, but live. And stand up to your mother. (laughs) That’s more than a notion.

RG: That is more than a notion.

DP: (laughing) I know. But in “How to Make Love to a Physicist” she stood up to her mother when she was forty-two. It’s never too late, but if you do it sooner, there’s a whole lot more living you can do. More often than not, it’s not until we are older that we feel more entitled to assert ourselves, that we don’t have to answer to our mothers or anybody else. But that takes a lot.

For teenagers, I’m not deluding myself into thinking they’re going to get it, but maybe it plants a seed. I remember certain stories and what certain characters did and said and how they stuck with me. Then I had a whole new understanding of that when I was in my thirties than when I was thirteen.

RG: Like when I saw Waiting to Exhale.

DP: Yeah—even The Color Purple and seeing the movie with my mother and her friends. It was a bunch of women going to the theater to watch this movie. I couldn’t wait to have daughters, so I could show them The Color Purple. After that initial scene of rape, my girls were like, ‘Why are you showing this to us?’ They liked the movie by the end, but I have to remember that different stories land on different people in different ways at different times.

But then I showed them House Party and thought that was a mistake—but they loved that!

RG: What do you want readers to know about your work?

DP: The thing that I am happy about is that these are stories about serious things, but there’s also joy there, I hope, because I had a lot of joy in writing these characters. Even though they’re frustrated, there’s a lot of longing and disappointment. Going through their stuff with them, I hope that people who read it enjoy that experience as much as I did.

And ‘enjoy’ doesn’t always mean that you’re happy at the end of it. There’s just a big exhale, and you’re reminded of something from your own girlhood or it makes you rethink a relationship or a thing you said or wish you’d said or wish you’d done or wish you hadn’t. I still read the stories myself and can engage with the characters and I hope that it does feel like an experience, that they go into the world of these characters. That would make me really happy. Get lost in there!

Deesha Philyaw’s debut short story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, focuses on Black women, sex, and the Black church. Deesha is also the co-author of Co-Parenting 101: Helping Your Kids Thrive in Two Households After Divorce, written in collaboration with her ex-husband. Her work has been listed as Notable in the Best American Essays series, and her writing on race, parenting, gender, and culture has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, McSweeney’s, The Rumpus, Brevity, dead housekeeping, Apogee Journal, Catapult, Harvard Review, ESPN’s The Undefeated, The Baltimore Review, TueNight, Ebony and Bitch magazines, and various anthologies. Deesha is a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow and a past Pushcart Prize nominee for essay writing on the website Full Grown People. Read more about her and her writing at deeshaphilyaw.com.

Rose Gorman is a former Fiction Editor at Apogee Journal. Based in Detroit, MI, she is the director and resident fellow at the Tuxedo Project, a neighborhood-based literary and community center. Read more about her work at tuxedoproject.com.

Upcoming Events

Official Launch Event: The Secret Lives of Church Ladies | September 3 @ 6pm | VIRTUAL EVENT | REGISTER

In Conversation with Adam Smyer, author of You Can Keep That to Yourself: A Comprehensive List of What Not to Say to Black People, for Well-Intentioned People of Pallor | September 17 @ 7pm | ZOOM EVENT | REGISTER