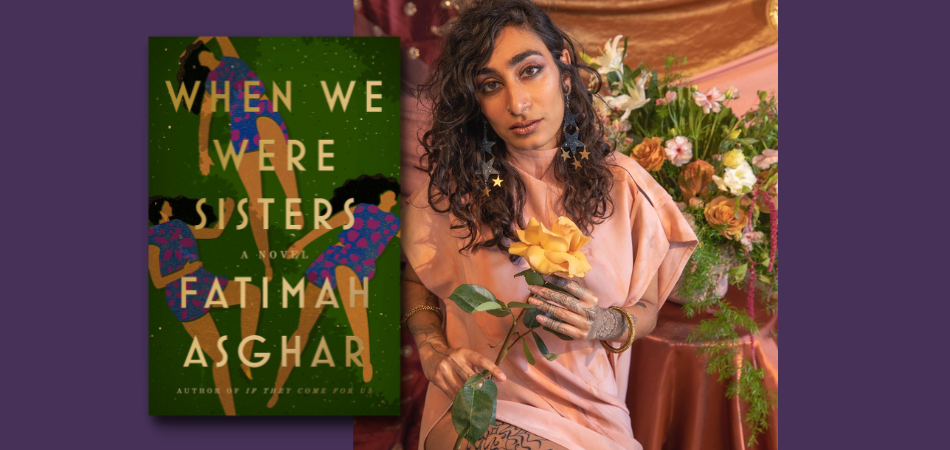

When three sisters are orphaned after the death of their father, their uncle provides them with cramped housing and little else, leaving the sisters to raise one another like “sister-mothers” as they grapple with gender, grief, and coming-of-age as Muslims in the wake of 9/11. Thus begins Fatimah Asghar’s When We Were Sisters, a haunting, searing novel that cuts right into the heart of family and belonging and reimagines what it means to nurture yourself and the people you love. Asghar’s protagonist takes you by the hand gently, carefully—with a vulnerability like none I’ve witnessed in contemporary fiction—and leads you right into the center of their world, a world as rich with longing and loss as it is brimming with hope. When We Were Sisters is radical in its form, a form that insists on working through trauma by re-imagining the body, the home, and even the English language.

Speaking to Asghar over Zoom one afternoon in October, I felt a similar sense of re-imagination; this time through their insight into making art under capitalism, staying true to your voice, and developing a consistent writing practice, a writing practice which, for Asghar, continues to evolve alongside them. Writing, they explain, is transformative; “If you allow yourself to really let the art flow through you in the way that you need it to, you will then allow yourself to be changed by the art.” I needed to hear this that day, and still today, and I’m grateful to Asghar for sharing their immense wisdom on writing, community, and craft with us now.

—Mina Seçkin

Mina Seçkin: In light of celebrating the publication of such a powerful novel, I’m curious, what makes you happiest, or most proud, about the book you’ve put into the world?

Fatimah Asghar: This book was probably one of the most difficult and most challenging artistic processes that I’ve ever taken on, and I think I’m really just proud of that. It was very important to me to write a story in the way that I wanted to, and to be able to break free and shut off a lot of the critical voices in my own self—being able to honor by own self by thinking, I’m just going to try, and this is what it’s going to be, and this is the story that I want to write.

MS: Did your understanding of the story that you wanted to write change as you were writing? And did you change with it?

FA: Yeah, absolutely. I think that when I first started writing this book, I didn’t exactly know what it was. I didn’t know really what it wanted to be or what it was doing, and as I started to write it more and more, it started to take more and more shape, and I started to learn things and realize things and feel things, and I thought, Whoa, this is really different than what I had originally anticipated. It’s important to trust that process. What’s really cool about art is that it changes with each thing that you make, and you change with it.

Everyone has told me, “It’s very clearly in your voice, and it’s very clearly your book, and yet it’s doing something that’s entirely different than your other projects.” This makes sense to me; artmaking is the process of evolving. If you allow yourself to really let the art flow through you in the way that you need it to, you will then allow yourself to be changed by the art, rather than trying to impose your will over the art. I think it’s such a beautiful thing, and I really felt that with this book.

MS: What does writing and creating art look like on a daily basis for you? And what do you do when those moments of resistance emerge when you’re writing?

FA: A few years ago, I was at the poetry incubator, and our two faculty members were Ross Gay and Patricia Smith. Patricia Smith had explained how she sits down and writes every day for five hours—that was what discipline and rigor meant to her, and it had to be systematized. Then we asked Ross the same question, and he said something along the lines of, “No, I just write whenever I want. If I feel it, I write.” I used to write a lot in the way of the former, and part of it, I think, was because I needed to. I needed to coach that discipline. There were some lessons I needed to learn through the art of practicing showing up everyday to write.

Now I feel that less, and I think about how you can get so caught up in making sure that you’re producing art, and that’s not really the way that art works. It’s very different for every single person, but for me, it really depends on the project, and it depends on what is being required and what needs to come through and how and why, and there are some times where I’m just not making art. It’s not what I’m doing. Instead, I’m living, I’m being a human being and I’m experiencing life, and I’m doing other things like logistics, like catching up on email or teaching or doing something else, and I think that that is important.

It’s also important to not over-abuse the muscle of creativity, and it’s important to understand that that muscle is something you have to be in deliberate relationship with. You have to nourish the muscle as much as you take from it. There have been times in my life where I’ve shown up every day, and there have been times in my life where I’ve been way chiller about how and when I choose to show up.

MS: Do you have books or films that you come to again and again for this nourishment?

FA: Yeah, I think that every writer does. In the acknowledgements for When We Were Sisters, I charted out the specific books that I felt like were very helpful, which include We the Animals by Justin Torres, Lord of the Flies by Willian Golding, and Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi. I had been thinking through certain things and getting permission from different writers—both in terms of the way that these authors write as well as what their writing opened in me in order to write a book like this.

MS: I’m in awe at the radical form that this story seemed to demand, and I especially love the usage of redaction and white space. You mentioned breaking free earlier—what did that look like as you were writing and constructing this novel’s structure?

FA: I think it was something that happened quite early on. As I was writing this and as it was coming in fragments, there were parts where I thought, Oh, this is going to look like this. I’m a very visual writer. This is something that’s true in my poetry, too. I pay a lot of attention to the way things look on the page. It’s the poet in me that really feels this is important, and I’m also thinking of the reader’s experience. When you slow things down or speed things up, or when you add a visual element, the experience that the reader has of the book and what it means to be present with the book changes.

MS: I kept thinking of this novel’s form as it relates to and contends with the body, too.

FA: Yeah, I think a lot of this book is about questions like, can you stay in the body? Can you stay in yourself? What does it mean when you can’t? What does it mean when there’s so much trauma that’s being shoved at you? I think a lot of those visual poems really get at the sense of what that feels like for the youngest character, and what it feels like to be in such a sea of grief and to have to contend and deal with that grief.

MS: Given the way belonging, and ideas of home, serve as such integral parts of this novel, I wondered if there is a physical space that you find inspiring to write in.

FA: It really depends. I wrote most of this book at my desk in my house. There was a retreat I did at Trout Beck, and it was a beautiful, beautiful space, with beautiful outdoors, too, and it also felt haunted. A lot came forward to me there. I get really inspired by having this kind of space and time, especially when I’m taken care of. When my needs are met, it’s a lot easier for me to write. For example, if there’s food, I think, I can just sit here and write. Being in nature really helps, too. It can get a bit more difficult to write when the creeping needs of day-to-day life slip in, and you think, Oh, I could write, but I also check these emails and I have to go do this thing and I have errands and I have blah, blah, blah.

MS: What advice would you have for aspiring writers, and what would you have wanted a younger version of yourself to know about writing and artmaking?

FA: There are so many things. I think one is that there’s a lot of pressure on writers to create and create and create and to get your name out there and your work out there, and I know a lot of this is because we’re creating under capitalism. But I think it’s so much more important to cultivate your own voice and your own artistry in your own time; to trust that your voice is important, and your voice is needed—but your voice is needed as its authentic self and not as a mimicry of anyone else’s.

It’s important for you to figure out who you are as a writer and what your voice is, and that takes practice. It takes a bit of stumbling, and it takes a lot of work in terms of really listening to yourself. Especially in an age where there’s so much content being pushed out all the time, where people feel like they have to do everything, I think it’s okay to go slower; it’s okay to really, really, really listen to yourself and think about the things that only you could do.

It’s also really important to understand that writing is transformative. The act of writing changes you, so you have to be prepared for the change, and you have to welcome it, and you have to humble yourself. Writing is the most humbling practice. Making art is humbling. Always stay ready to just be humble and to receive. That’s what you’re really trying to do; you’re trying to get yourself ready to catch when the thing comes, so you have to practice, and you can practice by getting out of your own way and by honing your craft skills, so that when it comes, you’re ready to catch it.

MS: Speaking of this pressure to create under capitalism, how do you grapple with your work becoming a product of sorts, or of selling your own self as an author?

FA: I think it’s so deeply complicated. When you’re an artist, that might be how you make your income, or it may not be, but it’s what your entire life is oriented around. What’s wild about art is that it’s probably one of the only, or at least one of the few career paths in which success does not translate to monetary gain. You can actually be an incredibly successful artist, and that doesn’t translate to making a lot of money, and I don’t think enough people understand that. Not enough people understand that some of their favorite artists who they think of as wildly successful are financially unstable and broke. We live in a world where you need to make money, and you’re expected to marry that with your own ethics. I think it’s important to ask yourself, What am I doing this for? What’s the reason? And it’s important to be honest, because sometimes the answer is that you’re doing it because you need money. You’re broke and you need to pay your rent, and this is just the reality of living under capitalism. But you can check in with yourself and ask yourself if you’re doing something to pursue money or ego, and if it’s something at the cost of your own integrity.

That’s going to be different for every single person. Integrity is not a static concept. Integrity is different for everyone, and it changes, and people try to enforce their projections of integrity onto you, and you’ve got to be able to define the concept for yourself. You have to have a strong enough sense of self to know what you value and to understand how you move in a world that is imperfect, in a world where many of us, if we followed our true integrity, would not be making any money. We’d all bow out of these systems completely. We’re not fully able to do that because we don’t have the privilege, the financial security, or the safety.

I hate the idea of branding. Part of the reason why I hate it is it makes us lie to our own selves. When you create a brand and you start to believe that brand and you believe what that is, then you actually don’t allow for growth, and you don’t allow yourself to change. Even with this novel, I got these questions where people were like, “Well, it’s so different than your other work, it seems like it has things that value different things. There’s something in it that isn’t as light as some of your other work,” and I’m like, Yeah, I’m a human who’s grown and tells different stories. This is one book, and another book I write might be different, and another book I write might be similar.

I’m a person who is growing at all times. So, if I make something that defies the idea of what you think of me, whose problem is that? It’s certainly not mine. When you’re writing and creating, you’re with yourself, and you have a responsibility to the ethics that you’ve created with yourself. You have a responsibility to the work and to your own families, your own communities, and your own loved ones. You have to hold yourself to the standard of, Am I doing this in the way that I have envisioned? Am I saying what I’m about? Am I doing this with the care that I set out to? When do I need to shift, and when is my old self boxing in my new self who is trying to emerge forward? It’s by asking yourself these kinds of questions that you can really know yourself.

Fatimah Asghar, author of If They Come for Us, is a poet, filmmaker, educator, and performer. She is the writer and co-creator of Brown Girls, an Emmy-nominated web series that highlights friendships between women of color. Along with Safia Elhillo, she is the editor of Halal If You Hear Me, an anthology that celebrates Muslim writers who are also women, queer, gender-nonconforming, and/or trans.

Mina Seçkin is a Turkish-American writer from Brooklyn. Her work has been published in Refinery 29, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She serves as managing editor of Apogee Journal, and her debut novel, The Four Humors, was published last November.