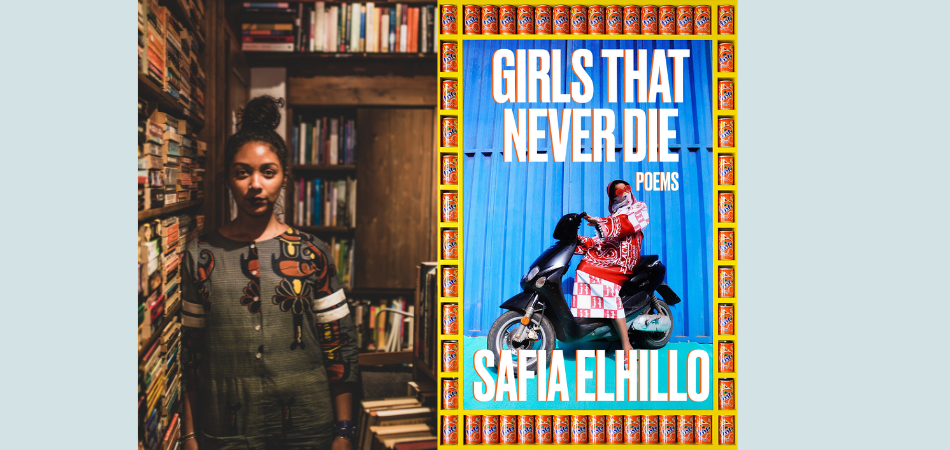

Safia Elhillo’s Girls That Never Die (One World/Random House, 2022) is an exploration of the burdens and hard-fought birthrights of womanhood. Ranging between music and memory, pomegranates and photographs, Elhillo wrests the story of oppressed women from their oppressors in an effort to rewrite their narrative. Over Zoom, I spoke with Elhillio about her subversive collection, her poetic origin story, and her neverending search for the perfect poem.

—Lakshmi Sunder, Editorial Assistant, Apogee Journal

Lakshmi Sunder: I’d like to start with a question that’s a window into your craft. If you could summarize your relationship to poetry in one sentence, what would it be and why?

Safia Elhillo: I know this is kind of cheating, but I actually have two sentences. I like to heal annoying stuff about language by having more agency to make my own grammar and choose my own syntax. Language can fail in a poem, and it makes the poem more interesting.

Also, for as long as I can remember, there has always been a feeling that there is a perfect poem that lives in my head—almost like an itch. By process of elimination, I inch my way towards this poem.

LS: What does your writing practice look like when you’re struggling to find inspiration?

SE: One thing that I will almost always do when I start writing is read some poems—a new poetry collection or collection of poems that I already love. It gets me excited about writing poetry. I’ll set formal challenges. I’ll encounter a word when I’m reading, and I’ll write a rhyme or sentence using that word.

At the end of the day, I can’t sit around waiting for something to happen to me. Sometimes I go for a walk and there’s a poem, or a hookah bar and that’s a poem, or an ashy patch on my calf is a poem. I cannot be a bouncer that doesn’t deserve a poem. I have to have an open door policy.

I also have a document on my computer called “Words I Like.” Usually, I’ll do a skim through the list to see if any words pop out at me and choose a couple words from the end of the list. I challenge myself to make a phrase or a line or a sentence incorporating some of those words.

LS: What are the most recent words you’ve used from “Words I Like?”

SE: I can actually check right now: innermost, isotope, oyster, apples.

LS: Language and the absence of language plays a big role in Girls That Never Die. In your first poem, “Final Weeks, 1990,” you write the word bride in Arabic and define it. In later poems like the first “Taxonomy” in the “Taxonomy” series, you write words in Arabic but do not define them. You also censor your writing using brackets. How do you make the decision to translate, include as is, or not include at all?

SE: The redactions aren’t real silences even though they aren’t sentences on the page because my hope is that you kind of know what I’m talking about. I’m interested in that kind of collaborative exercise—setting it up so you can think the word into that space anyway. I find it an interesting way to harness silence and take back the way that silence has been used, to make it loud.

For a lot of those definitions, the primary reader, I imagine, is someone who’s also a speaker of Arabic. With definitions, I try to stay away from defining a word as an act of translation. I like to ask, isn’t it strange that this word shares a root with this word, and what metaphor can emerge from placing those two words next to each other? I’m not so much translating it as a language nerd, but more like, here’s a word that we use casually and not often think about before using it. What other words come to mind when you think of this word?

LS: Music is integral to your recent poetry collection. Girls That Never Die itself is originally a song lyric from a song featuring Ol’ Dirty Bastard. How do you use music to guide your poetry while pushing past music’s stricter structure?

SE: A song can be such a time capsule, second only to scent. Even if it isn’t a song from my past, it’s a shortcut to make myself feel something. I won’t always listen to a sad song, and it doesn’t necessarily have to do with the content of the poem. When I was writing “Pomegranate with Partial Nude,” I was listening to Burna Boy. I will usually listen to one song on repeat for the whole sitting of trying to write a poem. If I were to make a playlist, everytime a song changes that would mark the passage of time, but one song creates a little container for me outside of time. I’d think I deserve a break if I listen to a three minute song and then move onto the next one. A single song is a tool to stay in the poem until I have done my duty.

LS: The structure of your collection in general, with its repeating titles, reminded me of a chorus wedged between verses. Why did you make the decision to repeat some titles and how did you decide which titles to repeat?

SE: I’m very fascinated by repetition. It’s a very ancient impulse, like I’m casting a spell. I also feel like a word or a phrase is never truly repeated and something changes between each utterance, though I will sometimes overuse repetition to my own detriment. Repetition is like a science experiment. I’m trying to figure out why a word interests me so much.

“Girls That Never Die” is one of the titles that repeats throughout the collection. That series was all formerly part of one poem. So the repeating titles are split up elements that I retained from the book-length poem.

LS: How did you revise to get the collection to where it is now?

SE: Part of the reason it took me so long to revise the book is because I tried to write this book the way I had written The January Children, and it’s just not that kind of a book. There were lots of really frustrating drafts because I was indulging in a lot of my other mannerisms in those early drafts—no capitalization, for example. I was thinking, this is how I, Safia, write a poem. A lot of those poems were frustrating because they looked and behaved like finished poems but there was no sort of sparkle. I was like, okay, maybe the problem is the form, and so I entered the book-length poem. What the book-length poem made worse was that, because I only knew how to write a project book, I was too zoomed into the subject matter and the themes. So, obviously, it was boring and really frustrating to read, but I couldn’t figure that out in the moment because I couldn’t see the forest for the trees.

My fundamental mistake was thinking this was a book I already knew how to write. So I put it away and started doing a 30/30 with my friend Hala Alyana. I wrote thirty poems that weren’t related to the book, and funnily enough, a lot of those thirty poems ended up in the book. I needed to zoom out and look out the window. I needed to capitalize some letters and write some prose. I needed to learn some new tools and forms. Then, I became the poet that the book needed.

LS: You mention your poet friend Hala Alyan and other poets in the back of your notes, like Louise Glück. How do these poets serve as a source of inspiration, and how do you keep them from clouding your own voice?

SE: I love to pollute my voice. I love my voice to be tainted by the poets. I am a product of things that have been taught by other poets. I love to make a record of that and cite my sources, and there is not also such a thing as my pristine untouched voice.

I started out as a youth slam poet, and I grew up going to open mics. A lot of my formative years as a poet were shaped by the feeling of going to an open mic and hearing someone whom I’ve never met before read a really stunning musical magical poem. There was also this feeling of a poem as ephemera.That moment when it clicks into place and you’re thinking, holy shit I’m listening to something magical, and there’s also the chance you’d never hear that poem again.

So many of those moments shaped me as a poet. There was a lot more space to experiment, and no record of it anywhere—just between you and the 45 people in the room. There wasn’t a lot of conventional vertical mentorship. A lot of it was just a bunch of people laterally communicating with each other—just me and a bunch of 16-year-olds trying to figure out what a sonnet it is. The mentorship was communal. My favorite poets were my friends and people I would see around in DC and run into at open mics. Real poets weren’t old dead white men or fancy people or whatever.

When I realized that poetry was something that I cared about deeply, I started seeking out books of poetry. YouTube was picking up, so there were poets I would look up on YouTube.

I remember watching a video of Suheir Hammad on Def Poetry Jam when I was in high school, and I’ve never heard anyone switch between English and Arabic in a poem before. It exploded my whole world. So much of what I think I’m doing in a poem now are a hundred percent because of being introduced to the work of Suheir Hammad as a teenager. None of this would be possible without her.

LS: I imagine that the poetry on the page is very different from slam poetry because the punctuation and spacing doesn’t often translate. How do you navigate that?

SE: The only difference is that I’m no longer competing in poetry slams. All the other stuff—about how it’s important to me that a poem works on the page and also has a viable life while read out loud—is retained.

A lot of the ways that I edit I learned from my performance training. How does it feel in my body? How does it sound to my ear? If vowels are memory and consonants are percussions, what is the interplay between those sounds and does it feel good to say?

Written poetry is like sheet music. I want to give readers information on how I want to say something out loud in the absence of my voice.

LS: How much space do you give yourself to stretch the truth in poetry?

SE: Because poetry is the only form I write in, it’s the only record I set for myself. The extent I allow myself to stretch the truth is in smaller details but not narrative facts. For example, my grandfather has glaucoma in his right eye but I changed it to his left eye because it sounds better.

So much of my revision is reading out loud, which is how I discovered that I wanted to use the left and not the right eye. The quickest way to find out if a line is not working is when you’re reading it out loud and you get stuck on something. I try to read it out loud to myself and see where I get stuck and see where my line breaks are not representative of what I want to say.

LS: What’s a line in one of your poems that encapsulates your mood today, especially because you’re feeling a bit sick?

SE: There’s a line in “Orpheus” where I’m making fun of myself—an image of bags of animal bones and corn cobs in the freezer. I’m literally making broth. I know that poem realistically is not a funny poem, but I think that line is very funny. Every time I’m making soup, I poke a little fun at myself.

LS: What’s a book you’re reading right now or is on your radar?

SE: Franny Choi’s new book: The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On.

I try not to read like a writer. As a person with a gaping absence of hobbies, it’s important to preserve that relationship with reading. Sometimes I just have to read the book because I want to read the book. It’s amazing if the book works to feed my well that way. But for the most part, especially if it’s a new book, I try to just read it for the sake of enjoying it. Otherwise, I lose my desire to read.

LS: How does identity inform your poetry and how does poetry inform your identity?

SE: It’s like a chicken and egg situation. I don’t stop being a poet when I stop writing poems. I’m still a poet when I go for a walk or eat chicken nuggets. So much of the work I’m trying to do is healing my relationship with things, but it cannot be that I’m only a poet when I’m experiencing trauma—that the things that hurt me are the only things worth writing or the most interesting things about me. I get inspiration when I’m at the club, not just when I experience things in the news. I move like a poet in my entire life.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Safia Elhillo is Sudanese by way of Washington, DC. She is the author of The January Children (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), which received the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets and an Arab American Book Award, Girls That Never Die (One World/Random House, 2022), and the novel in verse Home Is Not a Country (Make Me a World/Random House, 2021), which received a California Book Award, a Coretta Scott King Book Award Author Honor, and was longlisted for the National Book Award. With Fatimah Asghar, she is co-editor of the anthology Halal If You Hear Me (Haymarket Books, 2019). Her fellowships include a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, Cave Canem, and a Wallace Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University. She received the 2015 Brunel International African Poetry Prize and was listed in Forbes Africa’s 2018 “30 Under 30.” Her work has been translated into several languages and commissioned by Under Armour and the Bavarian State Ballet.

Lakshmi Sunder is a senior at the Kinder High School for the Performing and Visual Arts in Houston with a concentration in creative writing, and a rising freshman at Northwestern University. Lakshmi enjoys writing poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction about intersectional identity, familial dynamics, and dystopias that reflect reality. She has been recognized by the YoungArts Foundation, the Alliance for Young Artists & Writers, the Bennington Young Writers Awards, The Common Magazine, and The New York Times Learning Network. She has taken workshops with the Kelly Writers House and the Kenyon Review. Outside of Apogee Journal, Lakshmi works with #TeenWritersProject, Diversify Our Narrative, and Girl Up.