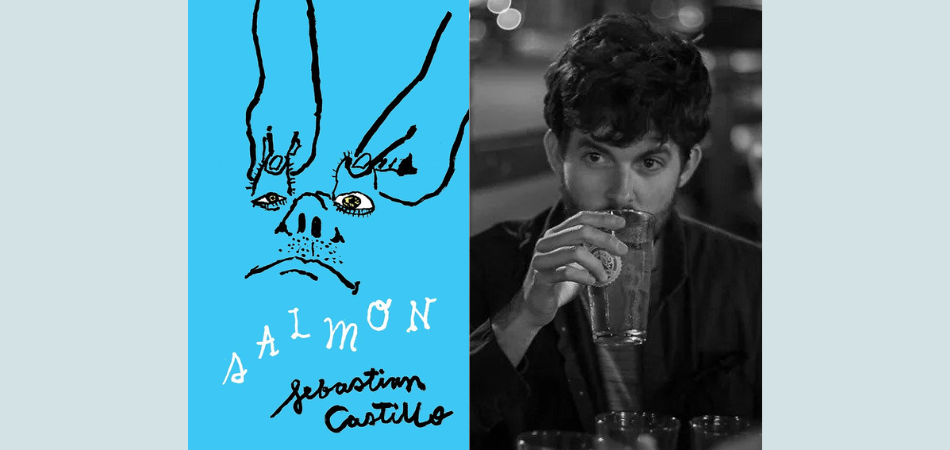

Sebastian Castillo’s SALMON is an absurdist coming-of-age-novel. Its hero, known simply as “the Poet,” completes his education and seeks employment in his field, but his options are slim. He settles for a job in the stock room of his local liquor store, and he relies on his parents to supplement his income. Soon he decides that this is no place for a creative spirit. He quietly leaves home for a new, mysterious nation: its name (always capitalized) is SALMON. It’s not the destination, however, but the surreal journey there that comprises the bulk of Castillo’s inventive novella.

This inventiveness is especially apparent in the narrative voice of the Poet. Formal, flowery, and verbose, it’s the voice of someone who keeps a cautionary distance from the modern world. It’s also comically pretentious, like Martin Prince reading the German Romantics. When the Poet needs money from his parents, he asks if they might “open their purse and slip [him] coin.” From his window on the train he observes that “one could spot a small hillock cresting over the horizon in the far distance.” In his efforts to make friends, he tries to engage people in “a bit of traveler’s chat” or to “invoke a bit of mirth at the table.” He strives to elevate his world with literature; he often fails. But that’s what makes him such a compelling character–the hero of an education novel whose own learning is spotty and inconsistent.

Both his education and his poetry are aspirational. He never commits any lines of verse to the page; he is too overwhelmed by experience. In a curious pattern of birds he sees “a spinning grey halo over the ocean.” He broods over the color of the sky, “a mustard sodium-glare mingled with leaky faucet.” But occasionally the voice shifts from the poetic to the perplexing: what does it mean for someone to have “the affect of a Prussian censor”? Many of the Poet’s descriptions are impossible to visualize, and yet Kit Schluter’s illustrations handle these primary images with fidelity. His depictions are naive and simple, but they too possess a sinister edge, often filling the page with negative space. This dark void corresponds well with the unsettling perceptions the Poet experiences en route to this enigmatic nation.

The trip to SALMON is wild. It includes a scenic ride on a passenger train, a brush with pirates, and a lengthy detour on an enchanted island. In the Poet’s telling, however, it feels less like a physical journey and more as though we’re probing his unconscious. Here Castillo shows off his penchant for the uncanny. Stones with mouths produce wine. A fungus turns men into weapons. He meets a chef whose nipples are shaped like long eraser heads (“to correct the many mistakes he has made in life”). These encounters fill the Poet with terror, amazement, and despair. Will he ever reach SALMON? Will he complete his “passage into adulthood”? Or will he be consumed by these childlike daydreams and nightmares?

In a short, informal lecture from 1907, “Creative Writers and Daydreaming.” Freud said that writing is like daydreaming and that the daydream is a wish to repossess a childlike imagination: “A strong experience in the present awakens in the creative writer a memory of earlier experience…from which there now proceeds a wish that finds its fulfillment in the creative work.” This process is aptly dramatized in SALMON. The Poet recalls a childhood in which his parents considered him “consolation” for their lost daughter, Clara:

I was not allowed to regale Clara’s room with objects and effects of my own…Perhaps it is for that reason — my inability to hang up posters and the like — that I turned to poetry. There, in the space of a stanza, I had the freedom to inject a great deal of pageantry and personality without interference. No one has read it, true, but that would not be the case for very long. (39)

Over the course of his journey, the Poet’s ego splits into several parts, and their conflicts become the driving force of the action. He meets his double, Sebastian, who happens to be heading to the same place. Together they endure a perilous adventure. Allow me to make the obvious remark that the double shares the author’s name. The synthesis suggests that Castillo has found an indirect route to writing about himself.

Castillo’s previous work also evinces a concern with autobiography. In Not I (2019), he filters his biography through a rigid grammatical constraint that results in a procedural, almost machine-like poem. In SALMON, he borrows the tropes of the coming-of-age-novel, but the action obscures more than it illuminates. Still, the author does reveal some parts of himself, particularly in his references to the Internet. He must be someone old enough to remember when it was a novelty, yet young enough to be completely absorbed in its trappings. The Poet’s literary dreams, too, seem as though they were hatched on the cusp of the Internet era. His voice betrays both a dedication to traditional literature and the debasement of high speed information consumption. The Poet (and by extension the author) resists disclosure in a way that is historically specific. In doing so, he reveals something about himself.

SALMON is not only concerned with the disclosure of the individual, but also with the stories of nations. Freud calls these national myths “the secular dreams of youthful humanity.” SALMON is merely one of many young nations in the book. Nearing the end of his travels, the Poet finds himself trapped on another new nation, an island without a name. It hosts many exiles from SALMON. Here he witnesses a speech delivered by its presumptive leader, whose revisionist history centers his own family as the rightful heirs to power. He then states cryptically that “the new regime had wished to eradicate any connection to their former nation’s past, and in doing so, create a fresh spirit of conviviality and unity.” The crowd is an assemblage of exiles: “excommunicated clergy,” “dispossessed artists,” “factory workers,” “malnourished children.” They passively approve of this plan to “delete” all competitive nations. Hearing this, the Poet and his double are in agreement: they have to escape this place–an authoritarian regime in its early stages–as soon as possible.

Authoritarianism, the artistic process, isolation, deserted islands, magic, “disgraced wizards”—while reading SALMON I couldn’t stop thinking about Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Prospero, its central protagonist, takes a break from his political duties to study magic. Meanwhile, his deceitful brother usurps the throne and exiles him to a deserted island. Prospero then uses his skill in the “liberal arts” (magic) to recover his sense of self, to judge his brother and, eventually, to offer forgiveness to all. But it is suggested (particularly in Derek Jarman’s 1979 adaptation) that the action of the play takes place entirely within Prospero’s dream, and that the story is really a childlike wish for a more just reality. Does Castillo wish for the same, from his own enchanted isle?

SALMON was published on May 9, 2023 by Shabby Doll House.