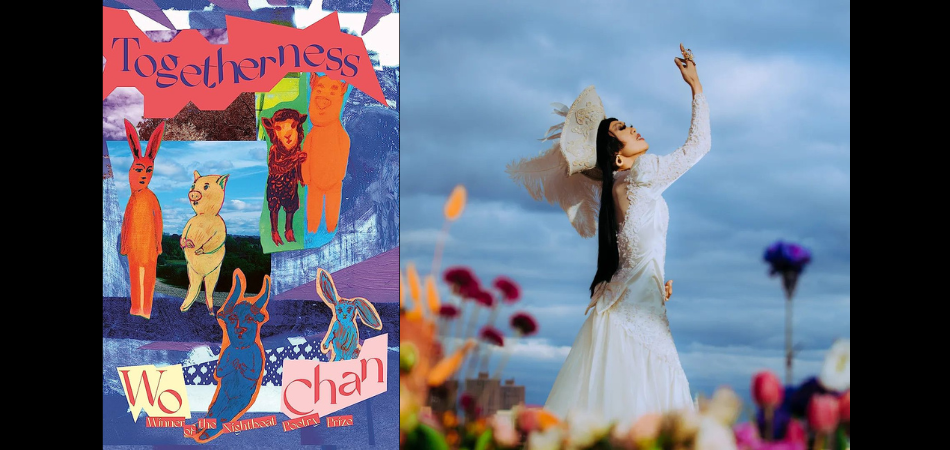

“sometimes we / are the smartest dumplings on the maps / and the dumbest,” writes Wo Chan in their debut collection, Togetherness (21). Or, put another way: people are complicated, capable of both wisdom and ignorance, care and cruelty. The poems in Togetherness take root in these complexities and entwine the overarching timelines and the small moments of lives lived in close proximity to one another. In these poems, Chan writes about the intimacies between family and lovers, the fear of deportation, and the joy of drag performance in spaces ranging from their family’s Chinese takeout restaurant to the glittering lights of Manhattan. This resilient and tender book offers dignity and pleasure as antidotes to shame and grief, leaving us with pearls of wisdom when we close its covers.

Much of the collection takes place in the Fortune Gourmet, a Chinese restaurant owned and operated by the speaker’s family in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Their lives revolve around the business, and no one is exempt from the labor of running a buffet; there are countless meals to cook, dishes to stack, and white customers to appease. The speaker recalls the summer they waited tables at the restaurant, where the menu items were adjusted to their customers’ palates and the heat and work were never-ending:

I bussed and airlifted soiled platters, refilled the dark unimaginable soda,

& made the face of a smile to the thousand hungry, post-congregate, mid-office

mid-life Caucasians, stoned truants, strange dates…

and my own family, each face distilled in the steamtable mirror… (66)

Running a restaurant is grueling and thankless work, and the speaker bears witness to these painful truths in the poem, “Reading the Yelp reviews of your family’s restaurant—a mistake.” The customer reviews to which the title refers are savagely negative; the speaker winces at an account of their oldest brother slamming a takeout order on the ground in a customer’s driveway. Another reads: “LACKING ANY LASTING IMPRESSION. THE FOOD IS GOOD BUT THE SERVICE IS AWFUL” (34). Despite all the Chans have done to appease their customers—working 12 hour days, changing recipes, struggling to communicate in English—their customers respond with unabating criticism.

Subsequent poems, however, tonally contrast the angry Yelp reviews. Stylized as typewritten letters, these poems represent the imagined voices of community members vouching for the Chans when they are threatened with deportation. One untitled poem, beginning with “Dear Your Honor,” is written in the voice of a local government official who cites the Chans’ tax-paying and hard-working nature as proof that they belong (12). Another untitled letter poem assures its readers:

In many ways, the Chan family has embodied the American Dream.

Kin Soi and Cheng Chao are always at their restaurant,

providing

for their family, still working hard even when most of our

neighbors have already returned home for the evening… (26)

The contrast between the Yelp reviews and these sympathetic reflections of the Chans present a bitter irony. These people who have “embodied the American Dream” work long hours to feed their family and their community, and in return they are degraded by their customers and can not afford healthcare (“Your mother has shingles and no doctor. Your father / has hypertension, no doctor” [34]). In addition to this, they risk losing everything they have worked for, as the threat of deportation looms over them , and they must rely on their neighbors to vouch for their contributions to the community.

The book’s speaker regards the Fortune Gourmet—and their parents—with mixed emotions. They are both thankful for everything their parents have sacrificed—their home country, their time, their dignity—yet feel guilty and aggrieved that their parents have endured these sacrifices for their sake. In, “i think about my mother and just begin to cry,” the speaker realizes, “mine is the life of vacation she peeps / through the keyhole” (10). The speaker’s mother has worked to her own detriment so that her children might have a better and easier life, yet the speaker seems unsure whether they deserve this sacrifice, referring to themself as “a liar” and “not lovely” (10). Both gratitude and regret for their parents’ sacrifices are mixed together—and the painful fact that the speaker’s family members do not accept the speaker’s queerness only complicates these feelings.

One of the central tensions of Togetherness lies between the hardships and wounds of anti-Asian racism the speaker shares with their family and the rejection they feel from that same family. In the poem “Ahem. She informs you,” the speaker interacts with a white therapist, telling her their family history in the second person:

your mother’s immigration, your

brother’s explosive and wasted life, your father’s reserved devotion to the dream

of you, your obsession for ballsack and cock. (41)

Juxtaposing their father’s expectations immediately beside their sexual desire, the speaker implies that their desire falls outside of the dreams the father has for his child. Elsewhere, the speaker describes their isolation from their family, how the other family members were always “living their lives around you, like a river to a stone” (25). Togetherness never outright names the tension and cause of isolation between speaker and family, but it surfaces anyway, a wound that still pulses with hurt.

Throughout Togetherness, Chan demonstrates an uncanny ability to devise unexpected and jarringly delightful metaphors beside lines that are completely straightforward, piercing and aching in their simplicity. My favorite instance is in the poem, “i’m so glad i got to see you,” where the speaker meets a friend at a pie shop in Gowanus, exclaiming, “your hair, a carrot’s root” (54) and then a few lines later,

what are all the words we know? let’s piece it together.

our mothers are intelligent; papers have us isolated; togetherness

can be brutal. yet we need it. there’s no justification. (54)

This is a clear-eyed proclamation that we need human connection, despite the ways that humans can be brutal. It is possible for both brutality and connection to exist in the same space. It is possible to hold space for the difficult and painful ways the people we love choose to show their stilted versions of love.

In the poem “Years Flow By Like Water,” the speaker recounts a Chinese myth of ten brothers each gifted with a different power, except for the youngest brother. The speaker is also a youngest sibling, and their brothers believe them to be useless, even as they try to shield their younger sibling from the harsher realities of life as Chinese immigrants in Virginia. This torment from their brothers—togetherness as brutality—exists alongside their brothers’ attempts at care. Later in the poem, the speaker will reiterate their love toward their family and their complicated relationship to their upbringing:

I love loving them.

I hate how we were raised, though it is done now…

Our parents:

they are in bed and resting diabetic, sewn in varicose veins.

The difficulties of the past cannot be altered, but at the same time, the speaker is learning tenderness towards their family and towards themself. While togetherness can be brutal, it doesn’t need to be. In a poignant, searching question, the speaker asks, “when will you let somebody love you, wo chan?” (60). This act of letting other people in, letting their love in, is a work in progress, but the process of embracing togetherness without brutality is one that takes shape through every poem, as the speaker learns to embrace themself.

Along with the more sober poems centered around family dynamics and the Fortune Goumet, Togetherness also includes raw and wild poems full of sex dreams, past lovers, piss, and lost pearls from the speaker’s décoletté “dropped far like seeds from a seagull’s asshole” (2), in which no image, no act, is taboo. In “Hair greased with the scent of bacon and five-spice,” Chan offers up a cloud of seemingly random fragments, from “taking your first step into a life of air,” to “huffing yesterday’s / underwear” to “meeting your father for the first / time,” to “peeing on your lover’s foot” (49). These are small glimpses of memory, a slideshow of the speaker’s life. They are presented without fanfare and without embarrassment, simply part of being human. Perhaps more than in any other collection I’ve ever read, these poems work to refute the shame that others try to press on people they disagree with or don’t understand. In their frankness and celebration of the possibilities and multiplicities of self, these poems offer radical acceptance and joy in the face of growing hostility and violence.

Togetherness is a powerful collection that breaks down silences around the intersection of being both Asian American and transgender. These poems lay bare the various painful experiences the speaker has endured at the hands of strangers, neighbors, and family members—vitally important revelations that demand us to pay attention and enact change—and they also unabashedly embrace pleasure and joy as forms of healing from trauma. Togetherness tells us that we are more than our wounds. It helps us see that existing and loving one’s self unapologetically in a cruel world is a gift not only to the self but to anyone struggling through similar feelings. Chan’s poems are honest, vulnerable, playful, and generous beyond measure, pledging, “i will always love you, no compromise” (70).

Togetherness was published on September 20, 2022 by Nightboat Books.