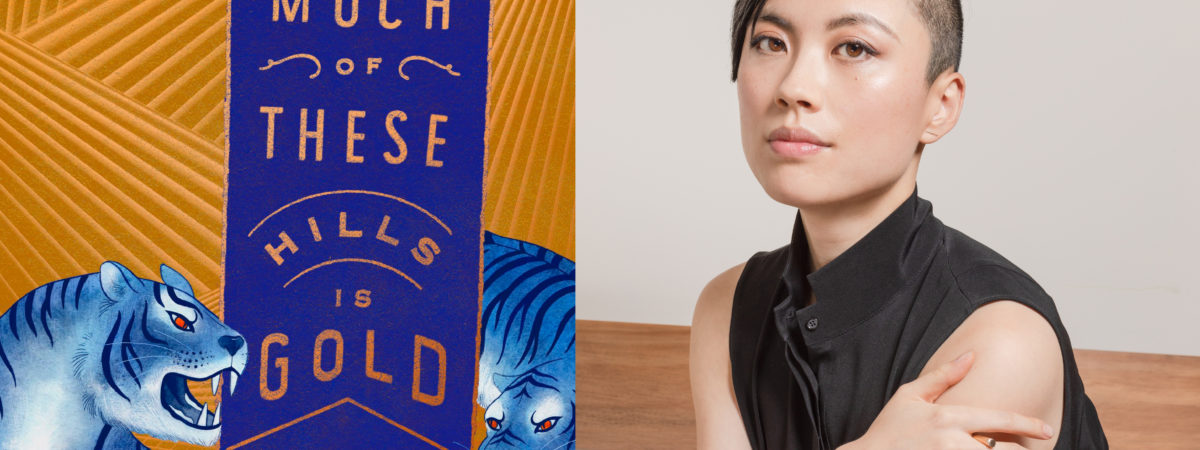

An Interview with C Pam Zhang

C Pam Zhang’s debut novel How Much of These Hills is Gold subverts stale and homogenous narratives of the Gold Rush, presenting the American ‘Wild West’ as a site of labor exploitation, rigid racial hierarchy, and a toxic mythology of American progress. Young siblings Lucy and Sam journey through a landscape that is historically-informed but richly imaginative, seeking to find a proper burial place for their father. Through their journey, we unearth memory and family history: we learn of the tribulations of their parents—immigrants striving to realize the social and economic progress promised by the American Dream. I was particularly struck by the interaction of form and content in this novel: the structure of the book mirrors the novel’s concern with the historical, cross-temporal resonances of trauma and racial inequality. The writer’s techniques echo the novel’s concern with complex intersections of gender, race, nationality, and language. C Pam Zhang and I spoke by phone in early March of 2020. How Much of These Hills is Gold will be published on April 7.

—Alexandra Watson, Executive Editor, Apogee Journal

Alexandra Watson: Let’s start at the surface: the book is beautifully designed—I love the gold pages! What inspired the design?

C Pam Zhang: I saw the cover for the first time as a fully realized design—the very first version was pretty similar to the final version. It had the markings in the background that evoked gold in the hills and the landscape, and the tigers. The biggest journey was in getting the tigers absolutely right. I’ve always hated having images of people on covers because I think they’re too limiting. I didn’t want the tigers to feel too historical or realistic. Because those are things that the book is not, and instead feeling contemporary.

AW: Speaking of resisting strict historical realism, the sections of the book are marked by years, but with the century, or two first digits, replaced by XX (i.e. XX62). I’m curious what inspired that choice.

CPZ: I borrowed that idea from the Haruki Murakami book, IQ84. In that book, he uses it to depict a slightly alternate, twisted version of the world. I like that idea because my book is labeled as historical fiction, which it is; but it also has surreal elements. It has fantastical elements, for one: having tigers roaming the landscape of the American West. That’s the reason the years are given the XX and also the reason that I stayed away from proper place names.

AW: Then at the same time, some details feel very based in specific histories—especially about the labor context. There are issues of exploitative labor, including the dangers of prospecting for gold, the precarious housing situation, and then the story of the 200 Chinese migrant workers. I’m curious about what research you might have done.

CPZ: I wrote the first chapter of the book not based on research, but on my own fuzzy understanding of that time period, sort of like stories that I’d heard over time. I did that deliberately, for one because I think the first draft of a novel can sometimes be stifled by too much research. So I took what I had learned but didn’t try to nail down every single detail. And then at the end, I went back and cross referenced specific historical facts. For example, there is something in the book that has to do with a real boat and for that one, I wanted to tie it really closely to the actual historical fact of Chinese immigrants building the transcontinental railroad and then being erased from history.

In general, in writing this book, I thought a lot about what history means and who recorded history is by and for: recorded written history is white history. And there is so much that is lost in the record—the lives of everyone from women, to immigrants, to queer people, to Native people who were not deemed important enough by white men. And so I do think that while it’s really important to think about the facts and to see how they influence the book, I also take a defiant stance: there is so much that cannot be recovered, and while it is a historian’s job to try to recover as much as they can, an artist’s job is an act of imaginative empathy, to resurrect the lost stories from the time period.

AW: That theme comes through explicitly with Teacher Leigh and Lucy’s fraught engagement with the history he teaches from textbooks, because of what it leaves out.

CPZ: Right. And there is a lot of shame too, when you don’t see your version of history or culture, people like you represented in recorded history. You feel a lot of shame, and self hatred, and sort of a desire to assimilate or to mirror whiteness that comes out of that lack of representation in the historical record.

AW: You have a way of sort of subtly indicting these these systems, this sort of Eurocentric, white-centric history, by presenting the multicultural landscape in which the American West came to be. The facts that the Gold Rush involved displacing Native Americans, and the fact that people from the global south, from present day Mexico were present as well—that definitely gets ignored in the historical record. I’m curious why this was the right setting for you to sort of explore these themes of race, place, and identity.

CPZ: Part of what I wanted to do with this book was skewer this American myth of being a self-made person—that if you try hard enough, there is equal and ample opportunity for all. I mean, you see that even in the present day. Before writing this novel, I worked in tech, and tech is kind of the modern Gold Rush. As a young person, and as an immigrant and a child of immigrants, I believed very deeply in this idea: as long as you work hard enough, you will be rewarded because the playing field is level in America, and indeed it draws a lot of immigrants here from their home countries. And it was only as I got older that I realized how false and also pernicious this myth is because then the dark flip side of it is you believe that if you didn’t make it, if you didn’t succeed, that that reflects a moral failing in yourself. The Gold Rush seemed like the ultimate setting to play with those ideas.

AW: That idea that not living up to the American Dream is a moral failing seems like one of the reasons that Ba falls into a deep depression. I don’t want to diagnose him, but there’s this yearning, this longing for more, and in fact the effort to get more ends up leading to the family’s downfall in some ways.

CPZ: It is incredibly toxic, it can warp you, if you take those myths of the self-made American person at face value, it can destroy you from the inside. And that’s something that I think that happened in historical times and is still happening today. You see this all the time, where people who are marginalized in this country sometimes like, turn it in on themselves. And in this case, I’m speaking more specifically of the Asian American experience, where you see Asian Americans who exist in this strange place in the contemporary American race conversation, where they’re not allowed to be white, and there is still a great amount of prejudice against them, but they’re also not as reviled as black and brown people. I see some Asian Americans try to cling to whiteness, and turn against other people of color. This is really just a product of that that toxicity.

AW: Ma was a really compelling character to me because she seemed like someone who had such a force and such brilliance, that in this context couldn’t be fully realized. Not to say that it’s all about upward mobility, but more in terms of her imagination.

CPZ: I would say that’s true. Probably of every member of the family. Ba also had a lot of potential and was embittered by the limitations in society that he saw for himself and sank into this, whatever you want to call it—depression, alcoholism. And for Lucy, her perceptions of self worth and identity are incredibly warped. I would say that Sam, in some ways comes closest to being able to live their fullest version of their life, but to go back to the way that siblings are foils for one another, Lucy chooses physical safety by falling in line with society, by trying to assimilate herself. With Sam, maybe you can applaud how Sam is a “more honest” version of who they want to be, but Sam’s life is fraught with so much more physical danger and Sam is punished for that in very different ways.

AW: I loved how the story took many unexpected turns. Based on the first section, I guessed the book would be all about this journey to find a burial place for Ba [the father of the two main characters, siblings Lucy and Sam]. It was giving me As I Lay Dying vibes as they carried his body around on the horse. But then we go back in time to see what life was like for the family before Ma died. We go even further back to see how Ba and Ma met. And then we go forward to Sam and Lucy coming into adulthood. Can you talk a little about the structure, and how it evolved?

CPZ: The structure was there from the very beginning. It really rises out of this belief of mine that all of us are deeply impacted by our past. And I think especially those of us who are the children of immigrants, there is so much that has come before us that affects everything about our families, our upbringing, and our lives, and moreover that a lot of that is kind of secret or buried. I knew it needed to go back in time in order to understand Lucy and Sam’s story when it comes full circle in the last section.

AW: Most of the book is in the third person, but one section is from Ba’s perspective. I’m curious about the decision to have that first person come in for that character and not, say, Lucy, who seems like the main protagonist.

CPZ: I don’t know if it was as much of a decision. In that section in particular, more than any other, it felt like I was channeling something. But when I step back for a minute, I would say that It felt necessary to open the book up emotionally. The first section in which Ba passes away, and the two children are burying him, they necessarily have to deal with that burial and that death pretty quickly, in order to move on and survive, they aren’t allowed to process it. And they’re sort of closed off from their own emotions about it, out of necessity. So I needed a way for the book to spend time on and honor those emotions. And it was only possible through that first person for me.

AW: I felt very deeply connected during that section, and it made me feel more connected to all of the characters. It’s really beautiful. Do you imagine that Lucy hears what he says?

CPZ: I think she hears it to some extent, but I’m not even sure myself if it’s really Ba speaking, or Lucy’s fantasy of Ba speaking.

AW: I appreciated that you didn’t italicize or translate the Mandarin in the book. I found myself learning words and phrases based on context cues – like “nu er” I knew was daughter, “ting wo” I knew meant “listen” or something like that. It felt like it reflected the real way that the characters spoke: Ma speaks more often in Mandarin because it was her native language, whereas Ba uses it more sparingly. Can you talk about what it means to you to bring a different language into your work, if there have been times in the past when you’ve done it differently, and how you thought about the choices of where and how to include it?

CPZ: I’ve always been against italicizing non-English words, because I feel like that is a concession to the imagined English-speaking reader, and not necessarily truthful to the texture of the lives the characters are living. For fiction, I always want to start from a place of what is real and truthful to the characters. And in this family, in particular, I think there is something lovely about the, as you say, the half-understood; what’s understood through context, this muddling—because it reflects the place that the children in the book live. They themselves have always and only learned Mandarin as a sort of broken thing. I wanted the reader to experience that effect.

AW: I’m noticing this pattern of this interaction of form and content: the characters actually talk about language and language barriers: when Lucy’s parents meet and they can’t communicate, they began to communicate one word at a time. I think what you do really nicely is to bring us into the concept through form, in this case, through integrating languages. Then you also give us a more explicit way of thinking about it through characters’ dialogue. I teach academic writing, and we’re always talking about how a writer’s form and content interact.

CPZ: This is interesting because you’re a writer as well, to exist on both sides of the divide. When you write, you can’t think about these things so explicitly, in the same way that you can’t think about, how faithful you’re being to historical facts, because it constrains you, but after the fact, that’s when you realize all the things that have gone into to the piece.

AW: Let’s talk about the relationship between Sam and Lucy. What is it about the sibling relationship that interests you? How does it interact with adventure?

CPZ: In a family, siblings often, deliberately or not, serve as foils to one another. I’ve always been interested in how a foil can be used in literature—the push and pull against them. So I think that right now in my writing, I’m interested in siblings, and I’m also interested in friendships between people who may identify as female because there’s an interesting tension—mirroring and jealousy, and envy and desire—that sort of leaks into those kinds of relationships. And in sibling relationships in particular, I find them fascinating because they’re relationships that can become so warped and destructive and toxic, but they’re so much harder to break than other relationships. I’m interested in what makes them connected and how far can you go from one another as siblings who still come back.

AW: You mentioned the relationship between two female identifying characters. Sam’s gender identity was one of the aspects of the novel that most interested me. For much of the book, you use Sam’s name rather than a gendered or gender-neutral pronoun. I was envisioning Sam as a boy at the very beginning of the book, until the detail about the carrot stuffed in underwear. Lucy sometimes describes Sam as a sister, but most often refers to Sam by name—as does the narrator. And then when Ma is still alive, Sam is much more consistently gendered as female. Can you talk a little about writing a gender nonconforming or trans character in a setting where this kind of language around gender identity wouldn’t have existed?

CPZ: Yeah, it is such an interesting and hard line to straddle, honestly, because I think it goes back to this point of: do you write a book that is sort of politically unimpeachable, in which maybe Sam would have a triumphant story where everyone would gender Sam correctly? Or do you write a book that perhaps treads into some dangerous territory or problematic views that are held by the characters themselves, but is also more complex and realistic and nuanced? Sam was the ultimate way of doing that. I did know that, from an authorial perspective, I wanted to at least give Sam a chance on the page to present the way Sam wants to present before I allow the sort of gendering of the time period and the gendering by other people to affect how the reader saw Sam, so that’s why I did avoid any pronouns that would gender Sam. For the first dozen pages or so, you would have this mental image of Sam before other people came in and gendered Sam. If Sam lived in the modern day, they would probably go by ‘they,’ but I don’t know because they didn’t live in the modern day. There is an interesting way in which both Sam and Lucy play with presentations of gender and femininity or masculinity to exert some small amount of power in their lives.

AW: Were your early agents and editors understanding of this choice?

CPZ: My editor and my agent never said anything about this. They were always behind this from the very beginning. I got no pushback on this at all. But I will tell you about this interesting experience I had when I had just started working on the book. It was in no way ready to go out, but I was at a literary conference. It was my very first time having one of those meet and greets with an agent where you give them the elevator pitch of your project. And I gave it and I said it was about the Wild West and also explores family and race and trauma and immigration and gender. And that agent, at the end of this pitch was like, that’s too many things. You can’t do too many things. I would suggest you simplify it. Which is just really, really wild.

AW: I’ve gotten that feedback before, too.

CPZ: I’ve learned since then, to be really protective of your work until it is sturdy enough to make its own way in the world, and to really be careful about who you share it with.

AW: I can see how letting someone else’s opinion could influence you, could strip the complexity from what you’re trying to do. In the last section, we meet Anna, a wealthy heiress from a family enriched by gold—the same industry that so drained Sam and Lucy’s family and community. Why was it important to you to include a character like that?

CPZ: Part of Lucy’s trajectory in this book, especially after she loses her family, is that she really loses her sense of herself. I wanted to reflect the situation of a non-white person in America, who only sees whiteness around her—I wanted to reflect that extreme: Lucy literally sees no one like herself after she parts ways with her family near the beginning of the book. It corrodes her. She has a desire to assimilate completely, she wants to be white. And so Anna was necessary as this device, a girl who theoretically Lucy could have been in another life, had she not been Asian American in these times. And she wants it so badly. It was necessary to show her problematic attraction to Anna, and the ways in which she puts that aside.

AW: I’m so struck by that image of the gold frame in Anna’s house, and Lucy thinking about how you could melt it down to feed multiple families. Compared to this tragic way in which gold has factored into Lucy’s family’s life.

CPZ: That was one reason that I think the characters of Anna and Teacher Leigh were important too. I didn’t want to paint this black and white portrait in which all the white people were just like horrible villains. They’re not all the people who are knocking down the family’s door, threatening them with violence; a lot of them are well-intentioned and perfectly kind and well meaning, but they still create all these psychological wounds.

AW: And from a societal perspective, you get to see how wealth is built from others’ labor. The book ends mid-sentence, and I don’t know if I’ve ever seen another novel do that. I don’t want to spoil anything for other readers, I’m just curious about that decision.

CPZ: There were times when I wanted this novel to end more neatly and less ambiguously, but the way I see a novel, is every novel has an arc. But the arc of the novel is not the entire arc of each character’s life. Lucy definitely ends the novel in a different place than where she began. I hope and imagine that she has a life beyond the pages that continues. And that she continues to grow and finds answers—but that’s not the person at the end of the book. And that’s how it had to end.

AW: It’s evocative! It made me think: what does she want? It’s making me think about her having a life beyond the page.

CPZ: I feel like we’re living in a time in which I embrace uncertainty and complexity more and more. What irks me more than anything is, whether it’s fiction or news stories, that sort of like want to wrap all of the complexity and problematic history of America in a tidy bow. Or it’s like: these terrible things happen, but we can be happy, we all can be friends in the future. And I just want to really embrace that uncertainty and ambiguity, and I honestly think that all our dialogue would be a little bit healthier and more open if we acknowledged that instead of pushing hard for a clean ending.

AW: Do you miss the characters after finishing writing this?

CPZ: I don’t miss them because the ending is so open, I really feel like they’re off in their own world living their lives, so it doesn’t feel sad. They’re doing their own thing now and that’s great.

AW: I’ve heard people say, when they’re writing about something more autobiographical, especially when they’re writing about someone no longer in their life, it feels hard to end, because that means not spending time with that person or that character. I’m just interested in the emotional attachment to characters.

CPZ: That’s really fascinating. Honestly, I was kind of relieved to set them aside, though I really love these characters, because the book is in either a very close third person from a child perspective or that one first person. And these characters’ lives are so hard that it was emotionally draining to live with those emotions with them. I don’t miss plunging myself into that ice cold bath every single time.

AW: I know that your book tour must have been affected by the current restrictions on gathering due to the Covid-19 crisis. Can you tell our readers how to find your book, and do you have any virtual events you’d like to share?

CPZ: I would love for readers to buy the book on the Penguin Random House site or on Bookshop.org, an online shop that routes orders through independent bookstores. Independent bookstores really, really need us to survive; and we really, really need them, too, so that we reemerge into a diverse literary landscape where booksellers continue to champion small, weird, remarkable books. One favorite local bookstore is Green Apple in San Francisco, and I’m also a fan-from-afar of Skylight in LA and Brookline in Massachusetts. Virtual book events are the wild, wild west of the literary world right now! I’m excited to take part in two: a Books Are Magic reading (Zoom Link) on April 13th, and The Antibody reading series on April 21st.

Born in Beijing but mostly an artifact of the United States, C Pam Zhang has lived in thirteen cities across four countries and is still looking for home. She has been awarded support from Tin House, Bread Loaf, Aspen Words, and elsewhere, and currently lives in San Francisco.

Alexandra Watson is a founding editor of Apogee Journal, where she has helped secure grant funding for community arts projects from the New York State Council on the Arts, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and Brooklyn Arts Council. She is a full-time Lecturer in the First-Year Writing program at Barnard College. Her fiction, poetry, and interviews have appeared in Yes, Poetry, Nat. Brut., Breadcrumbs, Redivider, PANK, Lit Hub, and Apogee. She’s the recipient of the PEN/Nora Magid Prize for Literary Magazine editing. Find her work at alexandrawatson.net.