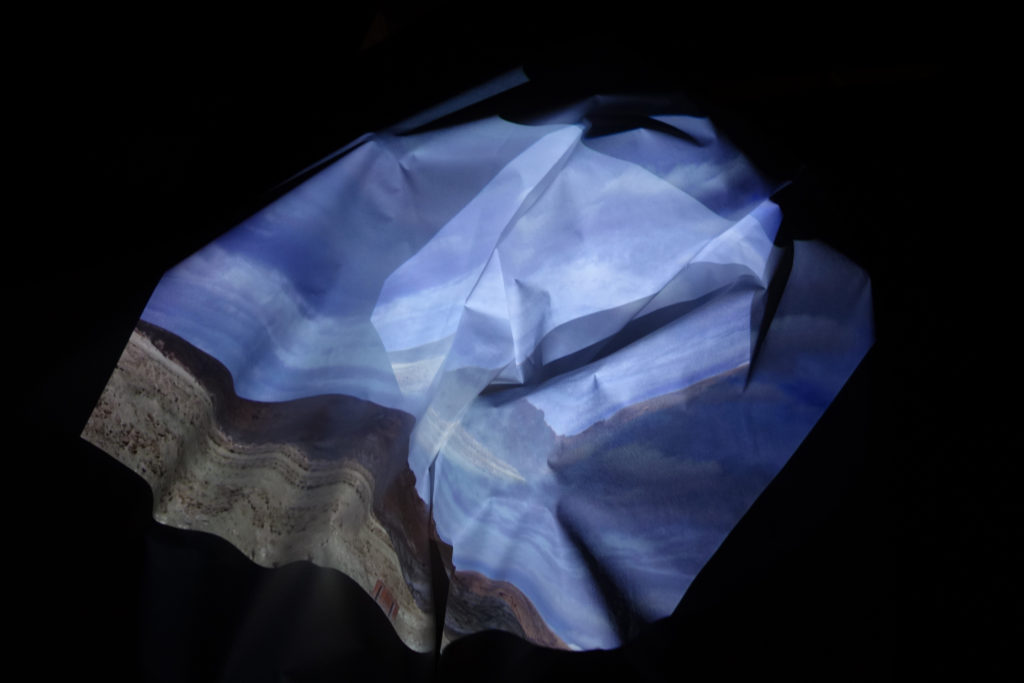

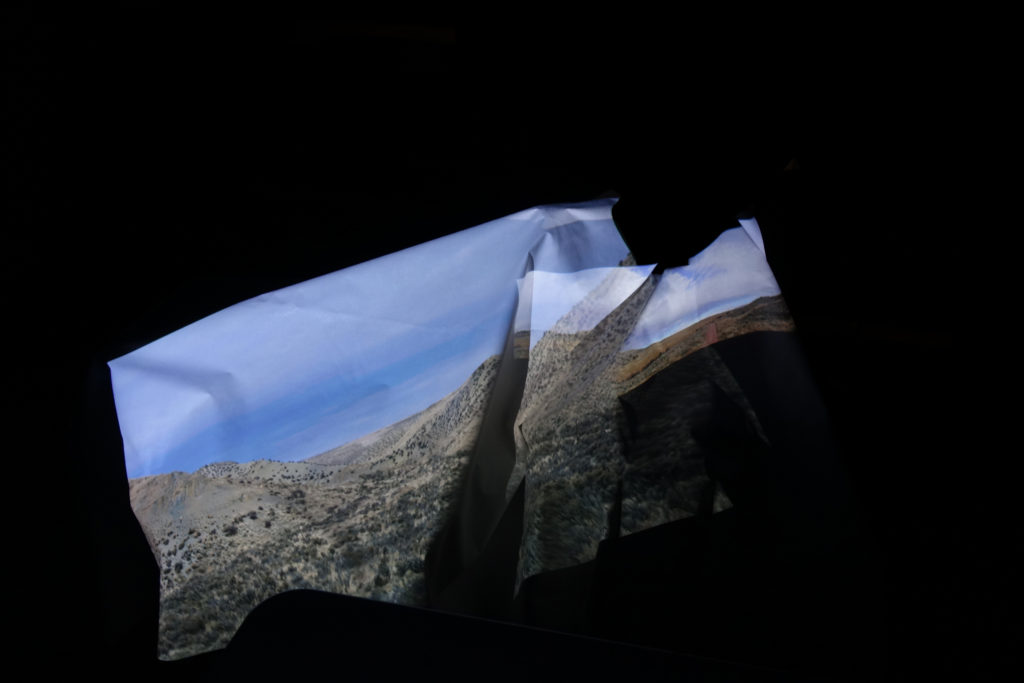

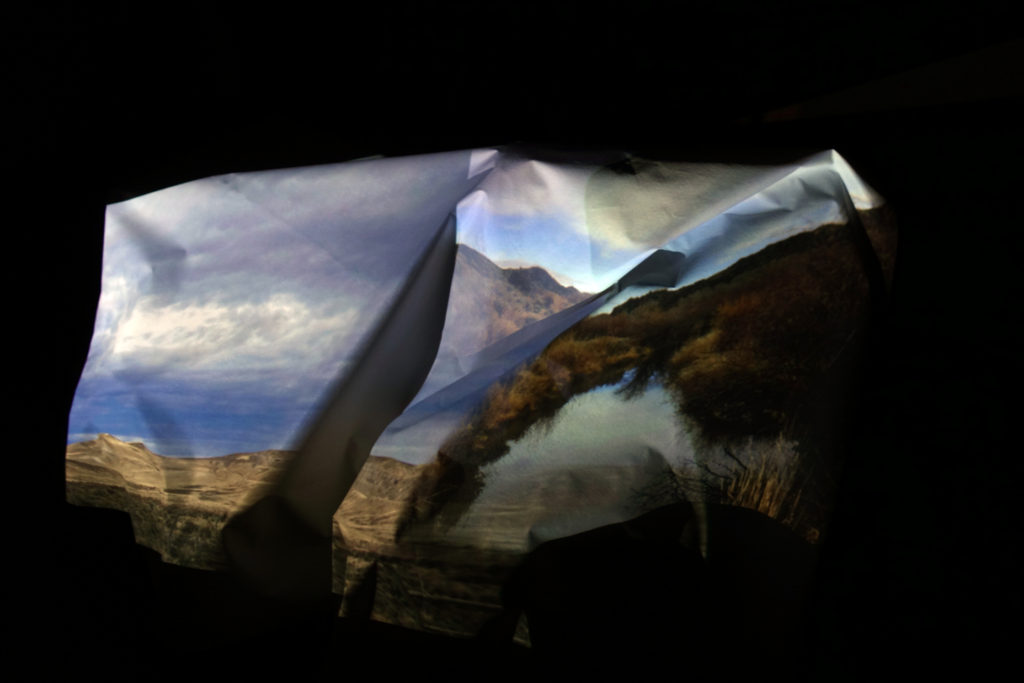

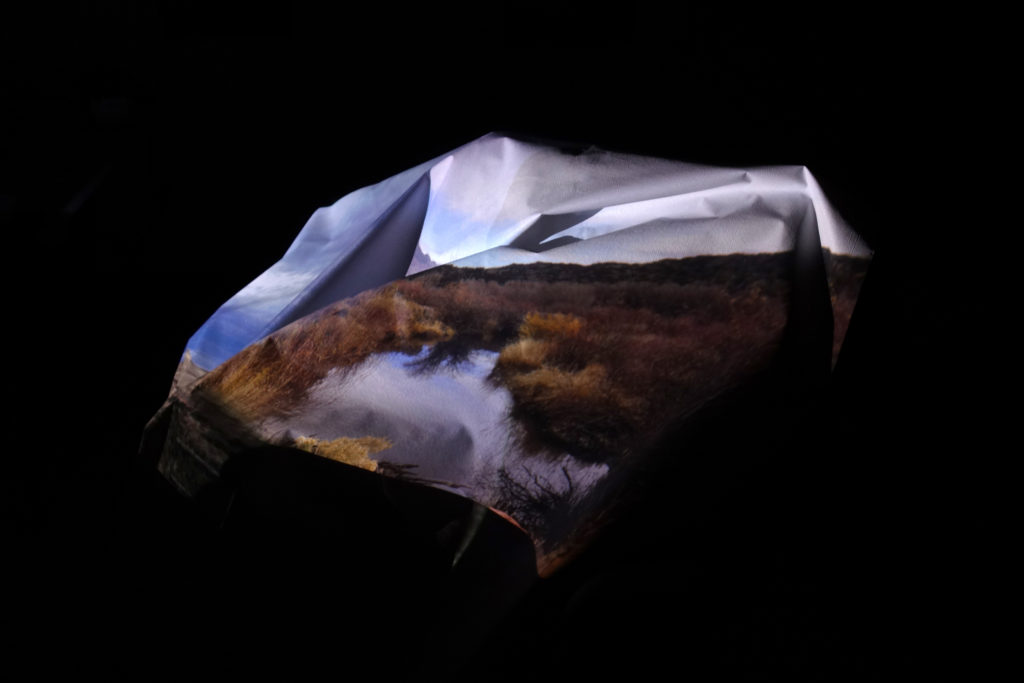

Cry River I-VII, 2015

Nicole Markoff

Two Poems by B.B.P. Hosmillo

Requiem for the Living

A jungle bolo

dropped and a young boy’s mother asked

where are you

going?

You saw it, departure built a house.

And burned it at once.

It happened many years ago. It doesn’t really stop.

//

Disappearance, what there is

in what a land no longer has is an evocation.

The sound of one’s heart in a minefield.

You heard it. A friend. A dead man. A dead sister.

The young boy of your skin,

who told you he wanted to see

the beautiful day he was born.

//

Did you lament or did you want to say how brutal.

Brutal

that the city had no idea how to host a life.

Shop mirrors caught no less than a passing of glance

to transit to another ride

to alienation. Somewhere

many people find just by walking.

//

You could not stay in one place, too.

You read a newspaper and someone’s begging

to see their first and only house.

You close your eyes and hear your mother asking,

where are you going?

//

You moved to another apartment.

And you are still the same. Colonized,

destroyed—it’s like the bones in one of your hands

were removed and you can’t find where they are.

At 3am you remember

one teaching of wealth: body is a property.

At 4am you remember what

an American soldier taught you: be polite

at all times.

You bow your head when blue eyes look at you.

You open the door because you don’t want to

be shot like the mother of your mother.

There is exactitude to call your mind a country

of gunshots.

At 5 am the calendar on the wall bears the face

of your eldest brother.

The man who’d said he was forever free

and later on was found headless.

He says, generous animals will be slaughtered

this week and nobody is going to stop it.

Guns will be for good and everybody will be

needing it.

He speaks and speaks and speaks

and speaks until sunrise, building the world

a map of those the day will lose.

spread out on an old junk newspaper, with a crucial part missing

—for Kartika Pratiwi

not the killing chant. not the killing field unrolled, extending from one’s mouth.

it might not have been understandable. shouldn’t you restore what happened then?

if fire, some people must’ve been there. if they’re shouting, help us believe

they’re dead: soeyanto, oslan, trisna, all the names you called

to remind a promise that it had to be a land, a diverse city,

but it couldn’t, a chinese

cemetery wasn’t quite such place.

/ /

the easiest way to accept what you know of the massacre is to leave it

in someone else’s dream.

/ /

after spitting on a yellow dog, bapak soeharto stirs his morning jamu,

asks if he has already left,

the man who went inside the house last night without permission,

the man who dug a part of the terracotta floor to bury his wound.

he answers himself by gazing over a high chair—something unseen sits there

each day, watching him put forgiveness and his photograph together

even if they clearly avoid each other.

today you’d like to be recognized and talk to him.

this is what you’d like to say:

i’m the man you burned. i will not ask why. the entire nation knows why.

three eastern brigades have lost count of their bullets since foreign is plenty.

even the air is a record as to how many outsiders are in the archipelago.

i can tell you each province that saw my shadow no different from the locals,

but where did you put me?

/ /

not museum in which the dead, in their appealingly noticeable silence, speak

of places, fragile as fossils, no one is allowed to touch.

not history since all regions there have been occupied

by heroes and their families and anyone who wants to appeal, to claim a little

land is too late.

not your hometown—what remains there is a lamentation,

but, like this banyan tree whose adventitious prop roots have made what resembles

a black house, anybody can get inside it.

it’s a trap according to a local legend.

whoever enters it will come out mad and injured.

/ /

unable to identify which his loss is and which is the world, a man

who needed temporary shelter saw it

and went inside.

perhaps he was wrong to do that

but he instantly recognized you, greeted, asked if you’ve already eaten.

a few others smiled at the reunion and went back to sleep

so they could continue farming under a tropical blue sky

or selling china-made merchandises in a market

where not once a preman roamed around.

you whispered something to him,

something no archive, not even the speaker of this poem would know,

and he hugged you tightly for hearing

that thing only the two of you could travel over.

he then said, if only anger is not waiting outside.

The Dakota Access Pipeline, Running Through the Heart of Native American Invisibility

Erika Wurth

When news of the Dakota Access Pipeline first broke, almost no one outside of Native American circles noticed. Although President Obama has initiated talk of a re-route, the pipeline is still set to run directly through Native burial grounds on Native land, and endangers the drinking water of those living on the Standing Rock Reservation.

This lack of attention is hardly surprising. The ignorance surrounding Natives, 70% of who live off of reservations, runs deep, and the debate as to why often seems to center around a kind of innocence. But are folks so innocent? One has to wonder, when so many claim a distant Cherokee ancestor, when we’re driving down streets named for Native tribes, when there are deeply grotesque team names like the Washington R*******, when some of the most popular Halloween costumes are Sexy Indian Princess or Warrior/Chief, when this is our country. I used to labor, intensely, under this notion of innocence. How otherwise to deal with folks making proclamations on how Indian or not I looked, how my people didn’t do well with the “firewater,” the deep, deep lack of representation in fiction, media, and the incredibly stomach-turning weirdness of when we were, because those images were so creepy, so far from human.

Originally, the pipeline had been set to run right through the town of Bismarck, North Dakota. But when the residents complained, worried about the inevitability of the pipes bursting, and crude oil flooding their water supply, it was re-routed through Standing Rock, right next to the reservation’s drinking water. This was nothing new. Though news of lead-infused drinking water in Flint, Michigan eventually spread, there was near-total silence except when it came to Natives, whose drinking water on so many reservations has been poisoned and poisonous for years and years and years.

Whenever these kinds of issues have been brought up, the response by non-Natives is generally abysmal. Most folks of color are used to the “get over it or get out” narrative, but, what’s most disturbing seems to be the version reserved for Natives, a one-two invoking the distant Cherokee ancestor and the sentiment that we need to assimilate. This is particularly disturbing given so few non-Natives understand that not too many generations ago, there were camps for this assimilation, otherwise known as boarding schools, where Native children were ripped from their families, beaten if they spoke their native tongues, often sexually molested by the folks tasked with “civilizing” them, over-worked, malnourished, and even used for medical experiments in a number of schools in Canada.

The recent acquittal of the Oregon Militia was a knife in the gut after the violence shown by police forces towards the non-violent Water Protectors in Standing Rock, who had led a peaceful stand-in often accompanied by prayer. In Oregon, the protesters had been armed, they had threatened violence, and there had been deep hesitation on the part of authorities to even move in.

It seems that this is when news of #NODAPL began to spread widely. There were articles everywhere, shared by folks from many demographics, and one couldn’t help but see the irony in a deeply, deeply ignored-but-not-ignored-but-“honored” people finally being paid an iota of attention. The only thing that was good about the Pipeline was that folks were starting to get that we are an actual ethnicity/culture, and that we are still here, and that we have problems.

But not long after that, the Halloween pictures began to appear.

It all makes a kind of horrible American sense. Non-Natives dressed up not only in goofy, fake Native costumes, but in their hands, signs proclaiming “Water Protector” or “NODAPL” with the “laughing” emoticon, or similar signs stating, “I godda job, Ima Water Pertecter.”

But who can be surprised? Just over a year ago, Amanda Blackhorse, an activist and social worker who lives on the Diné reservation, told us, “If we can agree that I should not be called a ‘redskin’ because that would be racist, then isn’t it obvious that the Washington NFL team should not use the name? Eighty years’ use of a racist term does not make a racist practice a legitimate tradition. It makes it 80 years overdue for a change.”

But so little has changed. Of course in each of those pictures “honoring” Natives on Halloween, there is booze in the background, or in the “Water Pertecters” hands. Why not throw in one more stereotype about Native alcoholism as “proof” that we’re not capable of being custodians of our own lands (ignoring that Natives actually drink less that whites).

Recently, activist Kelly Hayes pleaded with non-Natives to remember: there are people here that are drinking this water that have been here for thousands and thousands of years, people who are living with terrible schools, terrible water, people living in places where the infant mortality rates should put America to shame. Her feeling is that yes, we are protecting the water for all (one needs only to see the scale of the pipeline, and google the images of pipelines bursting, flaming, to know this) but to please, not erase Native people. But again, who is surprised? There are loads of images, and texts, and bizarre social media rants about the purity of nature before people came to America. And they erase Native people with the Edenistic notion of Manifest Destiny: the idea that this America was meant for Europeans, who are somehow Indians, and that it is all up for grabs. Or, as Native writer Sherman Alexie put it, “In the Great American Indian novel, when it is finally written, all of the white people will be Indians and all of the Indians will be ghosts.”

Because that’s where all of this is headed, right?

Invisibility. That’s the thing about being Native American. People want to talk about their connection to a mythical Native great-great-great-grandmother, and they’re desperate to find a way to diminish your connection to your Native heritage (if you’re mixed, you look white. If you’re not, you must not be traditional in some way). They want to think of us as really cool nature-unicorn people, but underneath their fetishization seems to be a very American rage. So are Americans innocent? Do they really not know we’re here? Their police sure do. And if they are so very Native, so Native that they can tell the rest of us how to be Native, why turn, as quickly as it’s inconvenient, to racist signs that proclaim how they truly feel about us?

This pipeline is trying to take our lives. Our real, not-just-for-Halloween lives.

For some reason, when I think about this issue, and it expands into this larger way in which Americans think about Native America, I think about the man who shouted expletives and flipped the bird at a six-year-old Diné child during a protest against the R*******. And at the same protest, another person saying, “Look! Real Indians! Look at that one with the braids.”

What are we going to do America? You can publish surveys, where you ask anyone who identifies as Native if they’re down with the R******* name and make it OK. You can tell me all about that distant connection, or you can tell me about how little we are, how invisible, you can proclaim your innocence, but when this country is doing what you know it’s doing, when even the most liberal among you will barely pay attention to us until we’re part of a big, environmental disaster, I am worried.

And in this new America-to-be post November 8th, I am even more worried. Desperately worried.

There are things, though, in all of this, that are beautiful. For so long, violence against the Water Protectors has raged. Images of bullet wounds, dog bites, huge bruises on faces have come across social media. And then, right at the worst of it, images of a herd of Buffalo coming to Standing Rock, moving quickly over the grass. There aren’t nearly as many as there once were. But they’re returning.

More of this America. Why can’t there be more of this?