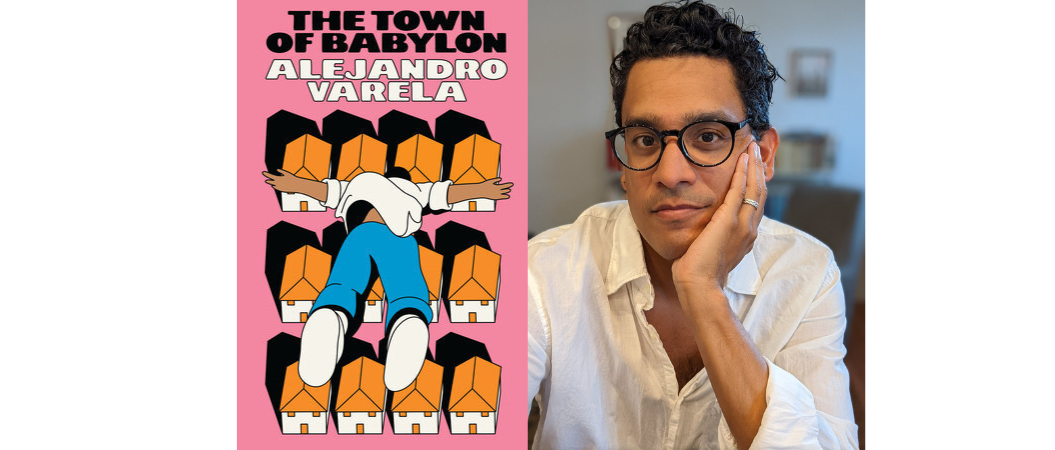

In Alejandro Varela’s debut novel, The Town of Babylon, the protagonist Andrés returns to his suburban hometown to help his ailing father. A queer Latinx professor of public health who now lives in the city, Andrés applies a radical, intersectional political lens to his hometown encounters, including with his best friend Simone and first love Jeremy. Here, he also contends with the death of his brother Henry from complications related to diabetes. Andrés’s relationships and interactions illuminate the social-political crises embodied by suburban America, including hypercapitalism, white flight, policing, and other legacies of genocide, war, and slavery. Alejandro’s novel reflects the kaleidoscopic yet incisive attention of the author to the social systems that pervade our interpersonal relationships, and asks how different society could be if we engaged in ethical community. We spoke over Zoom in June of 2022 about the community this book has nurtured, applying an unabashedly political public health lens to fiction, and the imperative to contextualize with backstory.

—Alexandra Watson, Executive Editor, Apogee Journal

This interview was edited for clarity and concision.

Alexandra Watson: What has it been like being on tour, bringing this novel out into the world—has anything surprised you that people have focused on or gravitated towards? Any trends in reviews and interviews?

Alejandro Varela: I wasn’t expecting people to connect with the book in the ways that they have. I thought it would be more detached. I suspected that readers would like it, and I hoped they would. And that they would comment from a distance, about the style, the structure, that it was funny—things like that. And sexy, hopefully. But I didn’t expect people to say, Oh my god, that was my experience growing up. Oh, my God, that’s my mom. I didn’t expect people to tell me how emotional it was for them, and how they identify with certain characters, particularly Henry and Simone. That was really touching.

I also wasn’t sure what to expect of our communities. I half expected every room I was in to be primarily white people. I don’t know why; I just got the impression that that’s how this works. And it’s true—most of the rooms that I go into are white audiences. But most of the people who reach out to me and try to connect with me about the book are people of color, and primarily Latinx folks, and queer folks. That’s been meaningful to me. Maybe because of what I have in common with Andrés, the protagonist, in that I was raised in a Whitetopia¹ of sorts in the suburbs. Primarily, it was a segregated neighborhood. As a result, I have always felt a lack of connection to the communities that I represent, or that people would identify me with. Until my 20s, I was often the only one of me in most of the spaces I was in. I was the queer friend in the straight group of friends in college. I was the person of color in a white group of friends. And it took me a long time to realize how important it was for me not to be the only one of me in the room. But that’s how I grew up. I was used to being the one, so I came to identify with that in a way that I think was unhealthy for me and for everyone.

I gravitated to Apogee, for example, because I was like, I’m not writing in white spaces—I cannot do that. I can’t share my work only with white people. And a lot of the things that were out there and available had white gatekeepers, journals and circles and reading groups. And so I started asking around, and r. erica doyle said, Have you heard of Apogee? I hadn’t heard of Apogee. She said, Well, they’re doing a workshop, Writing in the Margins. This is spring of 2015. That’s how I got connected. And I was very grateful for that grounding and affirming experience.

That part of the reception of the book has been wonderful because of my imposter syndromes. The jobs that I take on, I’m always like, I’m not smart enough. I’m not trained enough. And so to have acceptance from my communities in that way has been great. It’s been refreshing and validating. I love it. Because I was writing for me and us. I am one of those people who thought, What book would I want to read when I was fourteen?

AW: You’ve talked about this book being about people who aren’t connected to their community, and how this has terrible effects on their bodies and their health. It’s really beautiful to think about your book as creating community and helping you connect to community.

AV: For sure, it’s a bit of an intervention. For myself. I didn’t plan it that way. Or maybe I did, theoretically, but I didn’t realize it in practice. Or that it would have such an impact on me.

AW: Is there any aspect of the book that you’re surprised people haven’t focused on or asked about, or deep cuts that you hold close to you but other readers haven’t zoomed in on?

AV: Very few people talk about Simone. I’m interested by that.

I appreciated a couple of the reviews that came out that delved into the politics of the book—one by Marcos Gonsalez in Protean Magazine. They did a beautiful job connecting all of the lenses that people with multiple oppressed identities bring to the table. He read it through that lens, and he saw what I was trying to accomplish. I wish we could have higher level conversations about how this isn’t just about public health, it’s about the failure of America as a project.

There was a review in Washington Independent Review of Books where the tagline was something like, It’s not easy not being white in the suburbs. And I thought, If you walked away from this book, and you thought the white people in the book were doing all right, then you missed it. Sure, it’s harder [for non-white people], but everyone suffers when you oppress one group or when you don’t welcome people into the fold, and their health is worse for it. Not creating a world where everyone can participate has an effect even on the people who have much of the power. The 1 percent in the United States is less healthy than the 1 percent in the other wealthy countries in the world. It takes energy not to be social; community is natural. Eye contact when you’re walking down the street: that’s natural. I want to look at people. I want to see what they’re doing. I want to see if I’m safe. That’s a very animalistic quality. And when you can’t do that, whether you’re poor or rich, it hurts you. It affects you when you triple lock your door. When you know you are constantly looking behind you. That affects your health. That’s cortisol ticking up and down in your body all the time. I wanted folks to have that feeling when they read the book that it was bad for all of us not to have a shared community and not to welcome people in.

AW: Yes, you tell the story of Paul, who represents that kind of power in the book in some ways, white male power, but we get to honor what all comes before and how he got here. It’s more complicated.

AV: There were three books that were important to me in the writing of this: The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin, The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison and In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez. All three gave me ideas, confidence—they inspired me. I thought, Okay, I can do this. I can travel in time, I can switch perspectives. I can be epic, but still personal. And Paul, to me, is an example of this. He’s irredeemable until you know who he is and where he came from. And then suddenly, he’s a human. He’s the accumulation of experiences. I didn’t want to excuse him or his behavior or make an apology for whiteness, not at all. But it’s important for us to understand that actions are born from experiences.

Paul is the Polish kid in a mostly Irish-Italian community. I, too, grew up in a mostly Irish-Italian community, and there was occasionally a Polish kid. And the Polish jokes! That was surprising to me, seeing whiteness divided. When I was thinking about who I wanted to write about, I wanted to have a cast of characters who were all outsiders. Paul’s an outsider, even within that white world.

AW: The narrator is obsessive about unpacking these legacies of oppression and migration, breaking down every social interaction not only to the granularity of that particular instance, but also how these people came to be, who they are and where they are. At the very beginning of the book, on page two, the narrator is riffing about the owners of a local business, who are from the Indian state of Kerala. He says something that I think really set us up for this historical-political exposition: “I know very little about India, but if I hadn’t just mentioned this about Kerala, I’d have been as remiss as anyone else.” I’m thinking about knowledge as a burden that has to be shared. Could you talk about that compulsion, either yours or the narrator’s, to share knowledge?

AV: I definitely share that with my protagonists. The next book is called People Who Report More Stress. I come from a background of public health research and social justice work. And sorry to be so dark, but we’re all going to die soon. Sooner than we know. And I both want suffering to end and to see the injustice corrected. Selfishly, I want to see it. I want to see reparations in my lifetime. I want to see a national health service in my lifetime. I’m both angry and scared that it may not happen. So when I’m writing, I do so with a sense of urgency. I can’t waste time.

When I was younger, I didn’t love fiction. I didn’t love reading in general. In today’s parlance, I’m fairly certain I had ADHD. I couldn’t concentrate, stay focused. But at some point, probably in college, I became more of a reader, out of necessity, and I thought, fiction is not for me. I need to learn everything I hadn’t learned before. I picked up only historical nonfiction. It was years later that I started writing fiction, and I thought, Oh, man, I need to be prepared. I need to read every bit of fiction there is to catch up. But always with the intention of trying to communicate some of these urgent things. I’m gathering that this urgency is the thing that people love or don’t love about my writing. All the negative feedback I’ve gotten has been: it’s just a sociology lesson. You know, it’s not even fiction. And I’m like, I knew what I was doing. I mean, it is fiction—I’d like a little bit more credit than that—but this is the platform I have to say these things, and I feel compelled to say them in as clear a way as I can, so that someone can walk away thinking, That makes sense. Nothing more important than that.

A lot of these higher level concepts [health behavior theory, epidemiology, biostatistics] I learned in public health school, and I’ve been obsessing about them for almost twenty years. We live in a moment where reparations for slavery are still a little too lefty and radical—most lefties don’t even want to touch it. But to me, it’s common sense from a public health perspective—there’s nothing clearer. There’s nothing that would make our society better than reparations, and land back to the Indigenous nations, because everything else will flow from that.

I realized that every time I say that, I risk being labeled kooky or out of touch. I try to talk about these things in an accessible way. And what better way to do that then? Interiority. There’s a scene where Andrés is in bed with Jeremy, and he’s looking around the house wondering, How did this white guy get this house, this second house, having barely finished high school? And Andrés traces it all back to generational wealth. And then makes an observation about reparations. I labored over that scene because it’s so small in the scheme of things, but I wanted someone to be like, Ah, right. You can’t be like, Slavery’s in the past. No, this white dude today sold a Civil War era gun that bought him a second house, and he didn’t even go to college. And we’re told meritocracy—it’s bullshit. So, yes, I share this with Andrés. It’s the thing that I will probably do for the rest of my writing life.

If I was going to write fiction, I was going to be unabashedly political. Maybe it’s too much—maybe I can’t just say “Haha, I knew I was doing it.” I’m forever trying to find that middle ground between the advocacy and the enjoyment, the entertainment.

AW: It seems like the knowledge is so embedded in the relationships between people—the political awareness feels like it’s coming from the narrator’s own obsession, instead of research. When you were reading other things during this process, it sounds like it was more fiction than it was nonfiction.

AV: Public health and the last twenty years of politicking are my passions in life and this became the medium for them. Writing is the medium for my public health work. Reading [in preparation for the writing] was mostly about how fiction works. How do you construct these things? I pick up books all the time, where I’m like, This person taught themselves so much. Writers who learned, watched interviews, read books about the stock market, for example. I didn’t do that. That doesn’t mean I didn’t double-check. What are the names of all of the Indigenous nations from the East Coast? Did I get that right? I read a lot about schizophrenia to write those scenes with Simone, but I didn’t want to come across as an expert on schizophrenia, right? I borrowed from personal experiences, but then I read and read. I didn’t want to get this wrong. Schizophrenia doesn’t get attention in this world. It’s like a horror movie trait. It doesn’t get any respect as part of the human condition. I didn’t want to contribute to that. It was essential that Simone had agency and dimensions. And I still don’t know if I hit all the spots there.

AW: That made me think about the fact that the hospital where Andrés goes to take his father is next to the psychiatric hospital where he goes to visit Simone. Are they part of the same hospital?

AV: There’s a massive parking lot between them, but they’re part of the same system because one company bought these places.

AW: That seems symbolic—what we normally think of as healthcare is the physical, the medical, and then there’s the separate psychiatric hospital, but they’re coming together into one entity, which is both a product of corporatization but also, maybe it illustrates the way we are coming to understand how connected these forms of health are.

AV: You have this massive parking lot full of SUVs, separating mental and physical health, as if they’re separate things. But the mental is physical. To try to separate our mental health from our corporeal health is the reason there’s so much stigma: you chopped off your finger, obviously, that’s your health. But you’re having a panic attack: that’s just you losing your cool right now. No, they’re related. They’re very much related. To think otherwise is to ignore the brain altogether.

AW: I’ve been thinking so much about the part you wrote about SUVs being their own little worlds that people feel safe in, especially in the pandemic. At first it was, Oh, pollution is down, no one’s driving, etc, etc. And then everyone went out and bought an SUV, so it feels even more true. That idea that you can’t get safety from being around other people. You have to get it through isolating yourself.

AV: Where I grew up, I felt it was us against everyone. I thought every home was its own army unit. And everyone was battling each other. If we’d had a better relationship with our neighbors, that would have reduced the stress in my parents’ life tremendously. Not because they were feeling attacked all the time—although that, too. But imagine if a few of the neighbors are like Don’t worry, we’ll keep an eye on your kids, your house. As opposed to always feeling like we were being watched, judged. It alternates extremely between being watched and being ignored.

I borrowed one anecdote from my adolescent life; I was twelve or thirteen. I was biking home, and just as I got to the door, I felt an arm on my shoulder, and this man pulled me off my bike, and then another guy got out of the car and held me while the first guy grabbed the bike. And they were like, What are you doing here? And I said, I live here. They said, No, no, we know the people who live here. You don’t live here. And they were like, There have been thefts around the neighborhood. Can you prove this is your bike? My sister heard something from the window, screamed for my mom, and my mom came downstairs and tore this man a new one, and then followed him home, screaming at him. He was a retired cop. He was with this vigilante buddy, just driving around keeping an eye out for things. We’d lived there longer than he had at that point. He’d been our neighbor for several years. I knew who he was, and he had no idea who I was. It’s difficult not to think of Trayvon Martin. I didn’t have context back then. I’m grateful it didn’t turn out worse.

But that stress for my parents: Okay, we’re not even safe around these neighbors. Now, fast forward twenty-five years: that man is friendly with my parents, and they water each other’s plants when they’re away, and my dad helped his son find a job. For years would wave to me from his patio when I would come home. I never looked up. I won’t look up. Maybe I should. I love that he has a relationship with my parents because I know it’s healthy. But I don’t give a fuck about him.

AW: You keep the narrative super tight around this town, the town of Babylon, even when the narrative jumps forward in time. I was interested in the fact that even when Andrés leaves towards the end and comes back, we don’t actually get to see his life in the city with Marco. Even though it seems like all this context that Andrés has gotten from living in the city has informed his way of seeing the suburbs now. Did you always know it would be that way?

AV: There were a couple of cut scenes between Andrés and Marco around the infidelity. But I was pretty intent on this being a return home novel. I had written so much about current city life and gentrification in all my short stories. Most of my narrators are what I call class jumpers. There’s the takeoff point, and there’s the landing, and this book was all about where he took off from, and trying to come back, and not being able to fit in where he left. Everything else I’ve written has been about not being able to fit in where you land.

AW: There’s this list describing the suburbs: “Pavement. Pavement. Pavement. Garage. Lawn. Garage. Lawn. Speed bump. Garage. Lawn. Brief sidewalk. Windowless factory. Gray stucco. Windowless office building. Eggshell stucco. Pavement. Traffic light. Liquor store. Pizza place. Laundromat. Deli…” It feels like being trapped, even though it’s actually more spacious than the city. There’s more green space, presumably, but it still feels so blocked, so planned, in a way that determines Andrés’s movement through the book. He doesn’t want to drive anywhere, but it’s hard to walk anywhere. There’s no sidewalk.

AV: The suburbs, or at least the suburbs that I’ve known, feel like a human devolution. It’s interesting to me that they’re aspirational because it’s like aspiring to be ignorant. It’s aspiring to have less. I’m generalizing here, and I give this a little bit of room, because I know there are suburban planning models that are quite great, and diverse across the board. But a lot of these suburbs, the ones that I knew, were really about escape and white flight. Or safety. Even for my parents, when they moved to the suburbs, it was safety—from the schools, from crime and noise. But cities are what we have to figure out before we can figure out the rest. This is where everything is happening. This is where we’re all butting up against each other. I don’t think cities are inherently more liberal. I think it’s because we’re just in each other’s business so much that we become accustomed to things that we wouldn’t otherwise, we become inured to our differences. On a subway car, you can’t help but to see thirty-five different cultures and degrees of queerness and just humanity. It’s quite amazing. It’s why it’s exciting for a lot of people who grew up in suburbs or in rural areas, or in super white communities to come here and be like, Oh, my God, humans don’t all look alike, and they don’t all have exactly the same experience.

AW: Suburbs get tied up in the American Dream. But your book asks–at what cost? The cost is not just personal, for those who don’t achieve their American dream, but it’s often at the expense of the countries that people are coming from.

AV: There are a lot of people who immigrate, and they have no choice. But there are plenty of people who do, who were like, I’m not suffering where I am, but life is better in the United States. We can’t blame folks for doing that. Let’s just keep an awareness that there are reasons behind the waves of immigration—the U.S. isn’t only creating chaos through economic and military policy; it is also constantly advertising itself. We are the movie that’s playing in every country in the world.

Brain drain is a thing, the quote-unquote ”highly skilled workers” leaving. There are countries who pay for all the training. Those professionals then leave to work in the United States. It’s like a win-win for the U.S. It didn’t have to train people. The country of origin paid for the training of that nurse or doctor, for example, and then they came here. That’s not the case with the parents in the book, but they leave their country, and eventually the city here, with an expectation that it’s better and safer in the suburbs. But as you said, at what cost? What’s left behind?

AW: The third person sections stand out in the book, telling the backstory of the parents, not just of Andrés, but also of his peers. I’m curious about how those sections came about and why you decided to tell them in the third person.

AV: Some of that was practical: Andrés couldn’t have known all that stuff about Paul’s dad, for example. I thought about keeping one narrator only—maybe there’s a conversation, maybe Paul tells Andrés, but it didn’t seem feasible. It made sense to me that an omniscient voice would give the history of everything and everyone, like in The Bluest Eye, where Morrison alternates between perspectives. When I read that classic work, I thought, I’m on the right track. In fact, the biggest lesson from The Bluest Eye was, you don’t need explicit connective tissue between each chapter. It doesn’t have to pick up where the last one ends. You can leave room for interpretation. Not everything needs to be accounted for. This is a book that takes place in ten days plus all the flashbacks. And I don’t account for every single day.

AW: Morrison’s work gives so much permission. There’s a confidence and control over the material that comes with being able to disperse information the way she does.

Out of all the backstories, one that I was especially drawn to and surprised by was Paul’s parents. The book obviously centers queerness, but here we have these characters living heteronormative lives. But we still get to see a fuller spectrum of their desires.

AV: Paul’s dad goes to this park-and-ride clandestinely to have sex—he’s not out and proud. But everyone I know is sexual and has desires and curiosities, and they’re probably as complex and interesting as the ones I have. [Laughter] I know quote-unquote “straight” couples who are open and polyamorous and who are sort of queer themselves and that doesn’t change their lives. They don’t go like, Oh my god, now I have to identify as queer. This isn’t to diminish struggle or solidarity, but to say that desire doesn’t naturally abide by rules. I also thought it was kind of hot that Paul’s dad was such a complicated human.

That reminds me: when I was visiting Justin Torres’s class, a student said, I was really nervous when I was reading your book that there was going to be this moment when Andrés comes out and faces all of this trauma from his parents and that the love they have for each other was going to be complicated by this lack of acceptance. I was shocked and it was really refreshing that it never came. That’s not to discount all the people that have terrible coming out experiences. My coming out wasn’t great. But it wasn’t the worst in the world either. Once I was empowered enough to own my sexuality, my family made the space for me to say it and live it, and then we never really talked about it again. It was just like, Okay, we love you just the same, nothing’s changed. I felt like that perspective was missing from a lot of queer narratives. It doesn’t have to be traumatic. And maybe presenting this path gives people freedom to be more accepting.

AW: Jeremy’s mother, a white woman, is the one who ends up having the most intolerant reaction. That pushes against this culturally dominant perspective that people of color are more homophobic than white people.

AV: It’s funny that you mention that because when I was living in Seattle, seventeen years ago, where I went to grad school, I attended a meeting about marriage equality. I don’t know why. I’m for marriage equality. But if I knew then what I knew now, my battle would have been for trans rights first. In any case, at this meeting the presenters said that their was research showing queer people of color were less likely to come out to their families, but white families were more likely to disown their children once they did come out, compared to Black and brown families. I think the working theory was that communities of color are tighter knit. We have more social structure, more bonds. And so yes, our parents may not approve, they may look down on our orientations and desires, but we’re still family. We can’t leave you out. Which I find really moving. Even if it’s not the highest bar. While I can’t for the life of me find that study, anecdotally speaking it makes a lot of sense to me. It’s a perfect example of what capitalism and white supremacy do. Our natural instinct is to stay together, until all these other systems of power and control come in. I spent my entire life being seen and not heard. It’s always like, how do I not rock the boat? How do I look nice, wear the right colors and my hair the right way, you know, all the ways that white supremacy wins. If you grew up thinking that bright colors were vulgar, then queerness is just like an outfit you should never wear because it’ll draw attention. So you have these families or these communities that naturally would be accepting, but who feel pressure from the outside to not draw attention, to be safe, to try and fit in the mainstream structure, to not be loud.

AW: That’s reminding me of Morrison’s work again, in the sense of respectability being a dangerous force, and how families reproduce the racial violence of the society.

AV: It’s absolutely that. I think about that now when my kids are being loud and it stresses me out, in a public space—my kids are shrieking at the top of their lungs at the beach, and I’m looking around being like, Oh my God, everyone hates us. Oh my god, we’re being too loud. And then I’m like, Oh, I’m channeling my parents. I’m channeling this idea that decorum is to sit and be quiet, and that’s more important than expression. It’s a work in progress.

AW: I want to hear you talk about the cover art. What do you see when you look at your cover?

AV: I see the protagonist Andrés observing, from the outside, flying over this stereotypical suburb. An observer either landing or perpetually looking out. Never really there inside. Rodrigo Corral is the designer, and Igor Bastidis is the illustrator, a local New Yorker. He’s fantastic. And he’s everywhere. At first, I wasn’t sure how I felt about the art. It was visually pleasing from the get go, but I guess I was afraid that that animated style would make people think my writing isn’t so serious. I’m so glad I didn’t go with that way of thinking. I’ve really come to love it.

AW: That’s fascinating. It feels like falling to me. There still is pleasure and fun in the book, I think the cover gives us an invitation to find the fun and the humor even in the political intensity.

AV: When I was working on the elevator pitch, my publicist, Rachael Small, at Astra House, who is wonderful, would say, don’t forget to talk about the humor of it. I do think the book is funny, because I think it reflects my neurotic style of humor. Deesha Philyaw, in her blurb, referred to the humor, and I thought, Thank God. So to your point, the cover does give it a certain degree of a levity.

AW: What can you tell us about the story collection?

AV: Right now it’s sixteen or seventeen stories, and I want to get it down to nine or ten, or maybe twelve. I don’t want to give people too much, and I’m afraid of treading the same territory with themes. I tried to sell that collection a few times, my agent, the indefatigable Robert Guinsler, did, and we didn’t have the best luck. I remember one editor came back and said, It’s just kind of mean to white people; the narrator sounds bitter against white people. I thought, well, yes, of course, but also No, it doesn’t.

It’s about a queer, brown, class jumping narrator very similar to Andrés. He finds himself in a lot of white spaces. The love of his life in all of the stories, or in almost all stories, is a white man, and that’s what he’s dealing with. It’s complicated when you hate the system, and a representative of that system is in bed with you. I mean, you can be a person of color who adheres to all of the tenets of white supremacy and be aspiring to that. And we know those people well—Clarence Thomas, I’m looking at you. I actually think most of the things I write are not eviscerating enough. The third book I’m working on… Let’s just say, I’m not gonna make any friends with that one. Conversely, The Town of Babylon is about making peace. Andrés keeps going back, he sees possibility, humanity. He may not pursue it. But he’s not saying everyone’s irredeemable.

AW: Even Jeremy—was he one of the Obama-Trump voters?

AV: I think he was more of an Obama-then-didn’t-vote. Center left. But oh, Jeremy, poor Jeremy. I think about Jeremy sometimes, and I think about Simone and Henry and I wonder how they are and where they landed. And who knows, maybe I’ll write about them again. I didn’t want the book to be a love story between Jeremy and Andrés, but it ended up being a love story between them. And people really love that.

AW: There’s a lot of warmth there.

AV: Yes, a lot of warmth. But they don’t end up together. And so people were like, But he didn’t choose love, and I’m like Yeah, he did choose love. He loves Marco. And he also chose practicality. That’s important too. Was he going to give up his life to go back to this guy? What would they have talked about? What would their lives have been like? Sometimes love is not enough.

AW: It was great talking to you. And finally talking about your book. I loved it. And I can’t wait for the next one.

AV: Thanks for reading.

¹Whitopia: “A Whitopia has to be whiter than the U.S. in general, i.e., right now the U.S. is about 69% white. A Whitopia has to be whiter than its respective region in the country, (east, south, west, Midwest), and it has to have had at least 6% growth between 2000 and 2008, and the majority of that growth has to have to come from white residents. And the final quality that is absolutely crucial to a Whitopia is that it has to have a special social charm, a je ne sais quoi, a special look and feel.” – Rich Benjamin, author of Whitopia: An Improbable Journey To The Heart Of White America, interview with Melody Nixon, “Rethinking Utopia” (2014).

Alejandro Varela (he/him) is a writer based in New York. His work has appeared in The Point Magazine, Boston Review, Harper’s Magazine, The Rumpus, Joyland Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, The Offing, Blunderbuss Magazine, Pariahs (an anthology, SFA Press, 2016), the Southampton Review, The New Republic, and has received honorable mention from Glimmer Train Press. He is a 2019 Jerome Fellow in Literature. He was a resident in the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s 2017–2018 Workspace program and a 2017 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in Nonfiction. Alejandro was an associate editor at Apogee Journal from 2015 to 2020. His second book, The People Who Report More Stress, is forthcoming (Astra House, 2023).

Alexandra Watson is a co-founder and executive editor of Apogee Journal, for which she received the 2019 PEN/Nora Magid Award for Literary Magazine editing. Alexandra is a full time Lecturer at Barnard College. She has had poetry and fiction published in The Nation, The South Carolina Review, The Rumpus, The Common, [PANK], Redivider, Nat. Brut., Yes Poetry, and The Bennington Review.