Gustavo Rivera discusses his translation of Puerto Rican poet Salvador Villanueva’s poetry

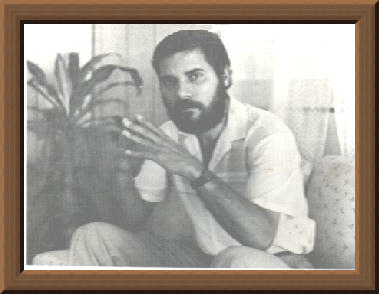

I first came upon the poems of Salvador Villanueva, one of Puerto Rico’s most overlooked postmodernists, sometime around 2010 through a blog run by Neftalí Omar Núñez Santiago called Existencialismo Pop, while I lived in Gainesville, Florida, where I studied, worked, and was a part of the local creative scene. I began to scour the internet for his work, finding some samples here and there, sometimes unclear as to whether they were written about him or by him. It was all very intriguing. I couldn’t find any of his books online. To practice my Spanish and get in touch with my culture—something that certain colonized Puerto Ricans will do at least once while living in the U.S.—I translated some of his poems I found. I emailed any contact address I found on the pages where his work appeared, even mailing a letter that was eventually returned to a PO Box address in Arecibo I found on a Geocities page. I asked my mother, who still lives on the island, for help, and she was able to score a used copy of Corazon en huelga (2009) after asking various bookstores. (Thanks Ma! I love you!) I was eventually able to get his latest collection Jodido (2012) and contacted the emails available in the two collections just mentioned. One person responded, telling me this writer was somewhere in Arecibo. Once again, I reached out to my mother who spoke to a poet-friend of hers, Luis César Rivera, who eventually spoke to Alberto Martínez-Márquez, a poet who lives and teaches in Aguadilla. One day, Alberto happened to run into Villanueva’s wife, Alma, and told her that a young writer living in New York wanted to meet him to translate his work and asked for her number. I spent a few weeks trying to communicate with Villanueva in a manner that I hoped would not be intrusive. At this point, I possessed a very strong image of the man before I ever actually met him. Based on his cynical minimalism and newfound deconstructionist lens, through which he would critique even those one would think he supported, I foresaw he might not want anything to do with me.

Luckily, that wasn’t true because. Since our first correspondence, we have become good friends. I met him officially in 2019, and he gave me a copy of his first collection, Poema en alta tensión (1974). Initially, I only wanted to translate his work to shed light on his poetry. I loved the stuff he wrote; it was incredibly funny and insightful, and I felt everyone else should know about this, too. But more time with him gave me the impression that our connection might be something beyond the material work we found ourselves doing. One day, we spent the entire day together to visit Librería Candil, driving through the curvaceous roads that cross the center of the island between Arecibo to Ponce. He told me stories about self-publishing, of setting up tables in front of the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras early in the morning, to sell books full of writing and art by his friends. I realized that maybe it’s not that history will repeat, but that we all might get a chance to play our version of roles that will always remain; however, the way we play these roles does not need to stay the same.

I found Villanueva to be ahead of his time, working a craft that would be called “meta-modern” by some, an innovative style in which the reader participates in the process of the author’s work. I was immediately taken by its apparent simplicity, which caused his work to stand apart from most of the poetry I knew from my island. Salvador Villanueva was one of the first writers representing reality in a form and style that consists of short and ironic language. According to Puerto Rican literary historian Josefina Rivera de Álvarez in Literatura puertorriqueña: Su proceso en el tiempo, Villanueva forms part of the Generation of ‘75, not to be confused with the Generation of the ‘70s, artists and thinkers who innovated Puerto Rican letters with various imprints such as Guajana (shout out this this sick work by Raquel Salas Rivera!), Mester, and others. Likely inspired by later productions curated by Rosario Ferré, Olga Nolla, Helena Mendez and Luis César Rivera, Waldo César Lloreda, and Eduardo Forestieri via their literary journal Zona de Carga y Descarga, Villanueva and others formed the Generation of ‘75, a movement that was open to not only new subjects but also new rhetorics, inspired by experiences on the island and the aesthetic shifts in contemporary Spanish letters, resulting in many writers who diverge in style, content, and more.

Villanueva and the Generation of ’75 ascribed to the ethic of “the personal is political,” which was made evident by the founding of the literary journal, Ventana in 1972, of which Villanueva was a directing editor. According to writer Rivera de Álvarez, this magazine openly embraced all new forms of emerging poetry. José Luis Vega, another important Puerto Rican writer, wrote in the first issue, “Every poem is an act of appropriation, an approximation of the world, an intent to capture it, to sense it, to make it congruent with the human essence,” focusing on individual interpretations as opposed to the objective realism of the earlier journals from the ‘70s generation. There is so much to say about how these writers revolutionized the literary arts.

Ultimately, both generations arose from a time that would create the conditions for present-day Puerto Rico, governed by animated cardboard figures that distort reality to promote private businesses and feed off the people living and laboring on the island. Inevitably, this disarray influenced some Puerto Rican thinkers like Villanueva to adopt a “non-poetic” sensibility. Villanueva makes his mark as the island’s premier Anti-Poet. His writing uses the brevity of the aphorism to reveal certain truths, often making universal remarks that illustrate something new and resistant to the ideas disseminated by the establishment. Villanueva’s writing, as well as those from the Generation of ’75 and ’70, are exemplary forms of grassroots activism from this era of American history (on the island and the mainland). In this moment, the fight for civil rights is at the forefront of people’s minds amidst universal disillusionment with the political status quo.

Right now, in light of the Black Lives Matter movement gaining momentum and causing political change, the racist and dehumanizing U.S. establishment is shivering in fear. A dedicated portion of the American people have been able to educate themselves and organize despite active repression. This was and remains a threat. The greatest weapon is knowledge of this nation’s racist history. This empowers us for the future. In the midst of recent uprisings, Villanueva’s work, especially his debut collection, appearing in the English language for the first time as Live Wire Poem (SVPRESS, 2020), speaks to this moment. There has never been a greater need to unpeel the layers of empty rhetoric we face every day, to do away with all the nonsense, and really see what we have as human beings in a rapidly dying world. The peoples of the world will have to do this themselves. Villanueva’s work helps ready the peoples’ mind for the level of self-evaluation necessary to achieve this.

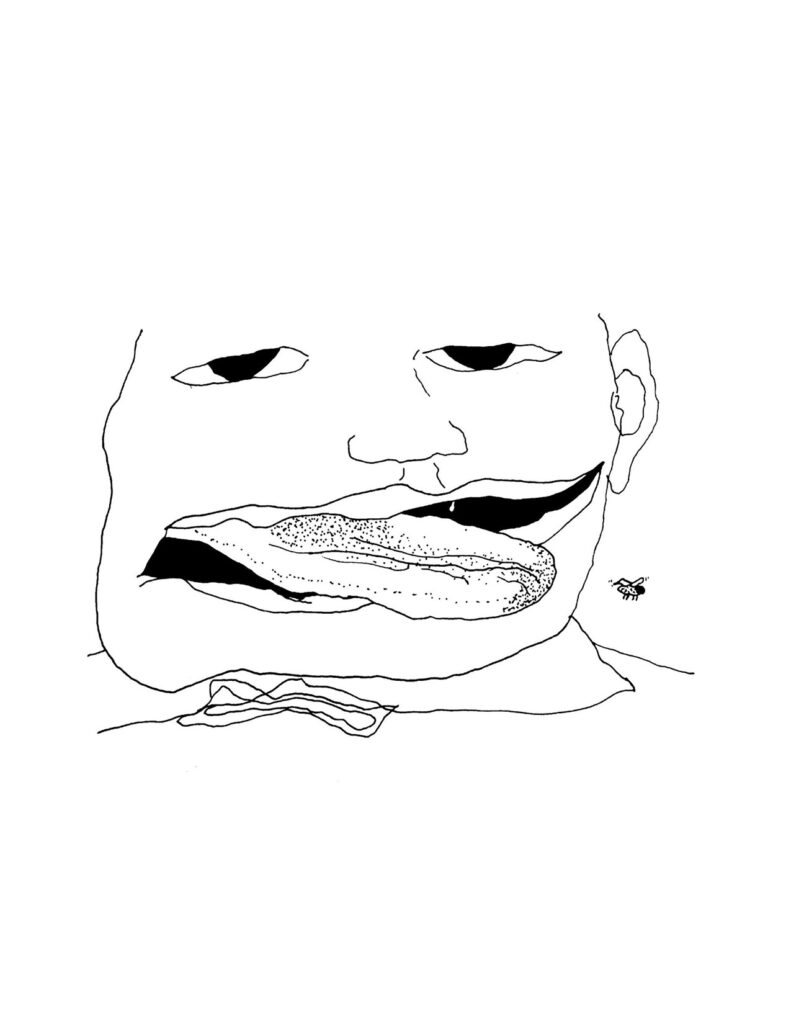

There is so much good poetry from Puerto Rico out there, especially from our modern writers, yet not enough people are uplifting and discussing these voices. I see a new movement right now, which provides hope. I’m glad to have, through SVPRESS and other literary collaborations, the chance to also help provide a platform for the voices of Puerto Rico, in its myriad incarnations, especially voices which might not be heard otherwise. I want to give thanks to the editors of Apogee for allowing me to talk about the poetry of Salvador Villanueva, which will be officially published this year for the first time in English, along with its original Spanish, digital representations of the art contained in the original publications from 1974, primitivist drawings by Pablo Romero, and a re-interpretation of the original cover and a portrait of the poet done by Puerto-Rican-Living-In-New-Jersey Amanda Paláez.

Poems and Further Elaboration on Salvador Villanueva’s Brand of Anti-Poetry

These six poems lead us through a web of linguistic constructions, some of which are accompanied by primitivist drawings by Pablo Romero. These components make up the literary machine called the Live Wire Poem, which reveals messages that are much more than what meets the eye, and challenges what it means to be literary, poetic, political, and human.

LOCALES

Tenemos la razón cuando discrepamos a la derecha;

entre nosotros mismos la perdemos.

LOCALS

We have all the reason to refute the right;

between ourselves we lose it.

VANGUARDIA

En esto de correr delante o detrás,

las gríngolas pueden resultar sumamente útiles

o perjudiciales.

Inclusive, no se trata de correr.

VANGUARD

In regards to straggling or forerunning,

blinders can result highly useful

or detrimental.

Indeed, it’s not about running.

COSTUMBRE EGIPCIA

Nos han momificado el espíritu a fuerza de palabras.

Que pongan la cena a ver qué ocurre.

EGYPTIAN CUSTOM

They’ve mummified our spirit with the power of words.

Let them set dinner and see what happens.

DIAGNOSTICO

Que quede claro

nuestro problema es uno de sintaxis

son partes de una granada de mano

los fragmentos

perdonen

que estalló a su debido tiempo.

DIAGNOSTIC

Let it be clear

our problem is a syntactic one

they’re parts of a hand grenade

the fragments

forgive us

which burst at its due time.

PRONOSTICO

A pique se irán, a pique,

a pique su estatuaria,

a pique sus violoncelos,

a pique su damajuana,

a pique el terciopelo,

a pique su polvo, sus poses viejas,

la misa y el padre nuestro,

a pique se irán, a pique,

en hora buena.

PROGNOSTIC

In smithereens they’ll be left, smithereens,

to smithereens their statuary,

to smithereens their cellos,

to smithereens their demijohn,

to smithereens the velvet,

to smithereens their dust, their old postures,

mass and our holy father,

in smithereens they’ll be left, smithereens,

in high time.

ORTOPEDIA

Ahora vemos claro:

se hizo preciso denunciar los parecidos,

destronar alguna estatua miserable,

echar la bulla,

reír detrás de las orejas,

a fin de corregir algunas viejas torceduras.

ORTHOPEDICS

Now we see clearly:

the denouncing of appearances was formalized,

dethrone some miserable statue,

shut out the noise,

laugh behind your ears,

to the end of correcting some old sprains.

This poem titled “8” is from a series numbered in decreasing fashion, experimenting with meaning, form, and style, interspersed throughout the entire collection, in a manner to resemble, what the author calls, a set time bomb, a poetic countdown towards catharsis and rejuvenation.

8

Al puro

al muy puro

purísimo

el prurito se le fue.

8

The puritan

oh so pure

the purist

lost his pruritus.

Salvador Villanueva nació en Arecibo, Puerto Rico, en 1947. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Puerto Rico. Fue cofundador y codirector de la revista de poesía Ventana; cofundador y codirector de la revista literaria En el País de los Tuertos; cofundador y coeditor de Ediciones Ricardo Garúa. Ha publicado los siguientes libros de poesía: Poema en alta tensión (1974), Expulsado del paraíso (1981), Fin (1987), Libro de los delirios/La comatosa noche (1989), El corazón en huelga (2009), Jodido (2012).

Gustavo Rivera es un educador, escritor, traductor, editor y agente literario radical, Boricua Bestial y previamente maestro mensajero, con trabajo reciente publicado en Apogee, Misery Tourism, además de otros. Es director de SVPRESS, enseña en colegios CUNY y vive en Brooklyn, NY.

Salvador Villanueva, born in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, in 1947, studied philosophy at the University of Puerto Rico. He co-founded and co-directed the poetic journal Ventana and the literary journal En el País de los Tuertos; he was a co-founder and co-editor of Ediciones Ricardo Garúa. He has published the following collections of poetry: Poema en alta tensión (1974), Expulsado del paraíso (1981), Fin (1987), Libro de los delirios/La comatosa noche (1989), El corazón en huelga (2009), Jodido (2012).

Gustavo Rivera is a radical educator, writer, translator, literary agent, publisher, Boricua Bestial, and former Master Courier, with recent work published in Apogee, Misery Tourism, and others. He directs SVPRESS, teaches in CUNY colleges, and lives in Brooklyn, NY.