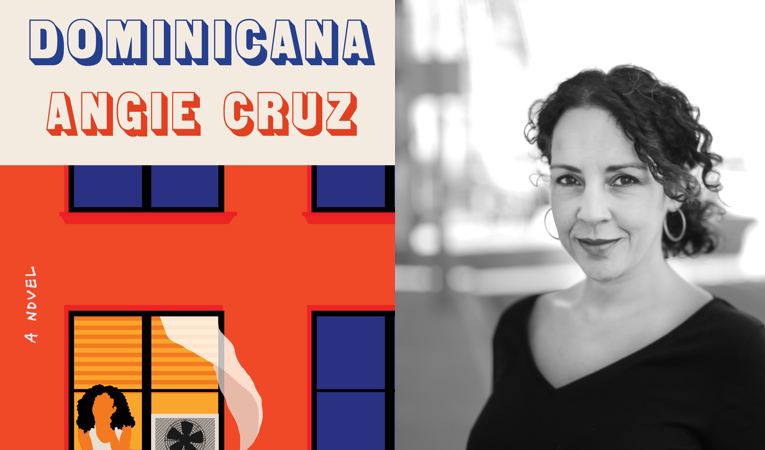

An Interview with Angie Cruz

Angie Cruz’s third novel, Dominicana, is an evocative, commanding story that digs into the universal themes of immigration, love, war, and family through a specific, voice-driven lens. Ana Canción, our narrator, is a 15-year-old girl in the Dominican countryside who marries and immigrates to Washington Heights, NYC in 1965 in the hopes of one day creating a better life for her family back home. Ana’s tender, raw voice is distinctive and full of pathos. As she struggles with abuse, the pressures of enduring for one’s family, her ambivalence about motherhood, and a growing attraction to another man, Cruz also illuminates the larger machinations of our world—from the Dominican Civil War to Malcolm X’s death to the competitive tensions between different immigrant groups in New York City.

Dominicana, out on September 3, has already been on ‘most anticipated’ lists of The New York Times, Time, Buzzfeed, and The Washington Post for good reason. This is a powerful and compelling novel. Angie and I discussed many topics, ranging from our intended audiences as writers of color, ‘breaking the rules’ of structure and perspective, motherhood, and whether writing ever gets any easier. Her answers were wise and resonated with me as a writer, thinker, woman, and person of color. I hope they resonate with you as well.

— Crystal Hana Kim

Crystal Hana Kim: Angie, congratulations on publishing Dominicana. It’s a voice-driven, lyrical, and heart-wrenching piece. The narrator Ana’s voice is so distinctive, so I wanted to start there. How did you come up with her character and voice?

Angie Cruz: The novel took me over a decade to write and in that time it was written in many different POV’s. I struggled because I was committed to write a novel about a woman like my mother who was asked to sacrifice her life for the good of the family, but I was also interested in the historical story of the 60s in both Dominican Republic and New York City. So for years I didn’t know if I should pull the camera lens far out or up close to the protagonist, Ana. In the end I decided to write the book in first person. So being that Ana only spoke Spanish, I had to figure how to write the book in English but point to Spanish. To do this I sometimes wrote entire sections in Spanish and then translated them. Sometimes the sentences when read out loud, the words are like mouth full of marbles, but I like it.

CHK: I think the translated-ness of Ana’s voice is wonderful. Your novel takes place in the Dominican countryside and in Washington Heights, NYC in 1965. Did you do any research?

AC: Maybe I did more research than writing? I am a little embarrassed to admit this, but it’s kind of true. I could spend hours looking at old photos and newspapers in archives. Or get lost in unclassified documents that are suddenly available online. For years I visited both the general archives in Santo Domingo and also the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute. And what often compelled me to write was what I couldn’t find. What wasn’t being said. Not surprisingly, the stories of working class women of color are under-documented. What one often finds is materials of people in power. So this absence or lack led me to interview people and look at photo albums from people in the community. And it also inspired me to grow a visual archive on Instagram @dominicanasnyc where I am collecting photos of Dominican women in NYC from the 50s to the 80s.

CHK: I feel you because when I was researching for my own novel, I also found that the stories of Korean women during the Korean War were under-documented. That lack fueled me, and it seems like it fueled you too.

I loved how Dominicana was clearly rooted in political events, but it was told through the lens of Ana. References to the Dominican Civil War, Reid Cabral, and America occupying Santo Domingo were all given from her perspective—you didn’t explain for an unfamiliar reader. Can we talk about audience?

AC: It’s a trip, isn’t it? Audience! I think often to that thing Toni Morrison said about Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. “Invisible to whom?” As an editor, she was interested in the kind of writing that was speaking to her. So when I read I often think who is the audience? Often, it’s not me. But I still read it and enjoy it and learn from it. So I write toward “my community” and by community it could be women, women of color, Dominicans, immigrants, etc. It shifts. But mostly I write toward a reader who will get it and if they don’t get it they will be interested in getting it and this means they may have to look stuff up. I mean, do you think about audience?

CHK: That’s how I think about audience as well. I write for my people, and I trust readers to look up references or historical context that they may not know.

Ana is sixteen when she immigrates to New York City as a new bride of Juan Ruiz. Through Ana, we see what life was like in Washington Heights in 1965, including the racism between immigrant groups, the colorism that her brother-in-law César experiences for being darker-skinned. We also see the domestic violence Ana endures, and how she feels stuck between duty to her family and her own independence. There are so many layers to your book, but it feels so effortless! When you write, do you know the themes you want to explore?

AC: I find that the layering happens in the revision. Don’t you? I think in my draft pages my characters often will have a two-dimensional quality and as I start building the world around them, put them in scenes with other characters, I discover what I want to pay attention to. So I guess I don’t know until I know. Or the writing tells me what it wants to be. I drive it to some extent, but it also drives me. As immigrants though, don’t you find that so many of us write about love, family, the struggle and war. It’s like how can we escape any of those things?

CHK: I agree with you. I’m driven by my writerly obsessions, which are often about womanhood, the tensions between independence and a responsibility towards the family, violence, war. Those layers are crystallized for me in revision too. You know, I feel comforted by all the similarities in our writing processes and interests, Angie!

I’d love to talk about the structure now. Dominicana is comprised of short chapters, some of which are only a few sentences long. How did you decide on this structure?

AC: It’s my third book and what I’ve learned and maybe this is true for all writers is that I have tendencies. I like to switch POV, for example. I think in circles and therefore my plots are looping around different time periods and characters. But with this book, I really wanted to challenge myself. I was reading novels, short ones, like The Stranger by Camus and Disgrace by Coetzee. I loved these books even if the narrators are infuriating. I loved how compact they are and loaded with politics, etc. When I started Dominicana I had just taken on an academic job in Texas and I said, my third book will be short, from one POV and linear. It was a challenge or constraint I made for myself. I thought I could write the novel quickly too because I knew the arc of the story. 14 years later I have a novel. It took me forever. I rewrote it in so many ways and no matter what I did the story came off too dark, heavy, overwritten. I couldn’t find the balance between the character’s story and all the historical research I wanted to include in it. I like darkness in novels, but it wasn’t working. What liberated the straightjacket I put myself in was that for one summer I only read poetry collections. I was blown away by Dawn Lundy Martin’s Good Stock Strange Blood and Solmaz Sharif’s Look and Rosa Alcalá’s MyOTHER TONGUE. Ha! White on the page, could do the trick was one of the big revelations. But there were many more of course. So I reworked the book hoping the white on the page would do some hard work. I allowed myself to bring in the letters, etc. Or to make some of the things that Ana may have discovered through hearsay be part of her telling.

CHK: Yes, in some sections, we get other parts of the story that Ana wouldn’t necessarily know—like Juan’s letters to another woman. I love that you break the rules here regarding how perspective ‘should’ work in narrative. How did you decide to do that?

AC: It will sound like a ridiculous thing to say, but it took me a long time even after I had been writing for a while to realize that a novel’s work is to say or do something new, or push the form, or do something that has never been seen or heard, etc. Breaking the rules is exactly what we should be doing, I think, but the trick is to get it to work. It’s easier to follow a model that has worked for others. But I’m interested in pushing the form, the sentence and exploiting how I move in three languages (English, Spanish and Italian) and four cities (New York, Santo Domingo, Turin and Pittsburgh) and allowing this border space of mistranslation, miscommunications, being lost, being found, fuel not only the themes in my work but also the style, syntax, structure, etc of my work. I’ve always inhabited a border space but it wasn’t until I started teaching and really learning the Eurocentric model of storytelling like having 3 acts, etc, the foundation of the majority of stories we are taught, that I had the courage and/or confidence to really play in my work. With my first book, Soledad, the book breaks a lot of the rules, but I admit, I didn’t even know the rules. I had no real “training” in an academic sense. So writing is less mysterious now in a technical way but a lot more fun because I have a lot more tools to experiment with form.

CHK: I think you absolutely push the norms of structure and perspective in Dominicana. I loved every new surprise in form, and it made me admire the work beyond just the narrative. As you’ve already mentioned, this your third book. You’ve also written Soledad and Let it Rain Coffee. Does it get easier? How was writing this book similar and different from your other books?

AC: I think it was Jenny Offill whose work I love and who I met while I was at Yaddo a while back who said something in the way that starting a new book makes a writer feel like they are a surgeon who in theory knows how to operate on someone but has forgotten how to use a scalpel. I think every book brings on a whole new set of challenges so I don’t find it gets easier. But I embrace the challenges and the growth that comes from that. When I worked on Soledad and Let It Rain Coffee I wasn’t working in academia and I also was not a mother. Those two things dramatically changed how I wrote and where. I had less time and heart space to get the work done.

CHK: Let’s talk about motherhood in the book. Ana’s complex feelings towards wanting a child and seeing the child as a trap felt so true. We also see the lineage of mother-daughter relationships through Ana’s relationship with her own mother, who pushed for this marriage to Juan Ruiz.

AC: Motherhood! When I first seriously started working on this book I lived in Texas. I was living in a ranch house on two acres, suddenly a home owner, married, pregnant, with a tenure track job. One would think I should have been happy but the price of job security, “upward mobility” and having a family was so challenging, and while my situation was not as difficult as Ana’s, I was able to channel the feeling of being trapped. When I was hustling from jobs and writing my books outside of familial responsibilities, I was free of debt and my time was mine. I think a lot more has to be said about what are the trades we make when we do the thing our families want us to do, like get a job a with benefits, get married. Have children. Things like happiness, self care, more free time, making art, being socially involved in our communities, living close to our communities are not always prized or seen as ‘success’ in the same way getting a “real” job or having a child is. And this is regardless of how moving away for that job can estrange us from everything we love, or trap us into a cycle of debt and consumerism in the end. So about motherhood, how to live one’s own personal desire, to be a mother, to be a daughter with mothers who worry about our well-being in this world that has proven to be harsh and unjust to women of color is something I am obsessed about in my work and in life.

CHK: Thank you for that Angie. I am constantly thinking about motherhood, both in my own life and in my work, so what you just said resonates deeply with me. Motherhood is so complex, and such rich material for writing. I have one last question for you. What are you most looking forward to with the publication of Dominicana?

AC: Honestly, the book has far exceeded my expectations. It hasn’t even come out yet. But I have already received so many loving and supportive responses from women around the country who have read the book, through Book of The Month, or galleys, etc who have shared with me how the book made them call their mother or how now that they read the book they have more compassion for a neighbor, a friend, an aunt. The theme of abuse, being so explicitly written about, has touched so many readers already. I am just happy it is resonating with people and I hope it continues to do so. I also appreciate so much your questions around the construction of the book and how I use language. Because in the end when it’s just me and the page, the act of working language, playing with language is when I am happiest.

Angie Cruz is a New York born Dominicana, the author of two novels, Soledad (2001) and Let It Rain Coffee (2005). She is the editor of Aster(ix), a literary/arts journal, and her work has appeared in journals including Gulf Coast, Kweli, NYTimes, Callaloo, and VQR. She teaches in the MFA program at the University of Pittsburgh. Her novel, Dominicana is forthcoming with Flatiron Books, Fall 2019.