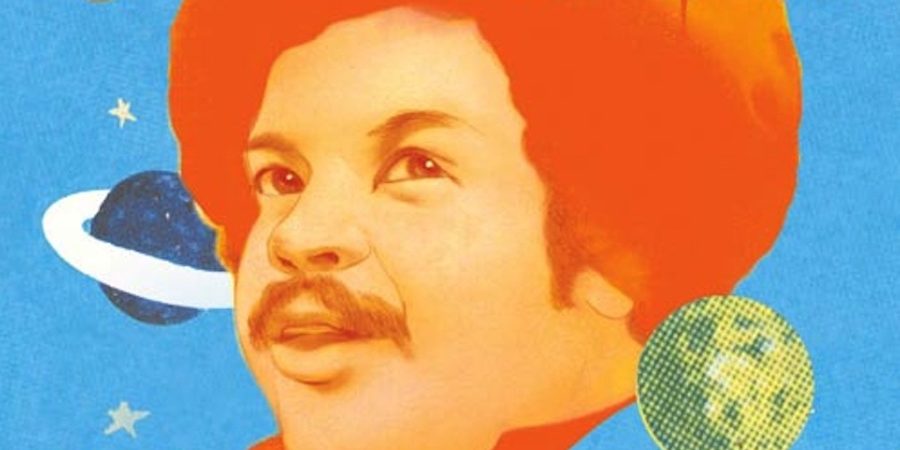

Tim Maia in Miami, 1963

Stoned & sandaled, with the Black Power afro & bad-toothed grin, indecipherable to Everglade

bohemians

who buy their herb from him—even his given name, Sebastião, registers, only, as a nasal honk &

two soft lisps.

So they call him Tim…

Brazil, his inscrutable origin, is still just tourism & rainforest to

Americans, Black Orpheus

& Carmen Miranda’s banana headdress. No one’s sure how he got here, to Florida’s nadir,

though his

alibi is “student” & he’s been singing baritone in a doo-wop quartet. This was before The

Boatlift, before Castro emptied

his prisons on the shore; before Spanglish threaded every salt breeze & before they realized

South Beach was sinking into the sea.

Before das kapital of Latin America’s young capital was weighed in cocaine metrics—no 8-balls

yet, no kilos. & plenty

of time, still, until Tim brings Soul to Brazil, becomes a homegrown Otis Redding of the open-

air discotheque, re-

makes those early doo-wop demos with cosmic-samba beats; achieves, as it’s called in pop

music, immortality.

No—it’s September ‘63, & the immortal’s still a bum. They still don’t know what the fuck he’s

saying, these floral-

shirted collegians, every vowel turning to wet sand in his jowls, every consonant whistling

through crooked teeth,

& even when he laughs, throaty, throwing his head back, a gospel choir trying to kick out of his

chest, the joke’s as unplaceable

as his accent.

But soon—they’re not sure why—they’re laughing too, & soon he’s partying

among them, parting the beaded curtains

of some Art Deco apartment—Beat poets on the bookshelves, endless bottles of absinthe & gin.

He stays

‘til morning, scribbling broken English love lyrics on a new bohemian girlfriend’s skin. “I’ve

slept in the street,” he’ll sing, ten

years later. Tonight, however, he stays awake, holding this strange girl close, so close that the

ink rubs against him, then away.

*

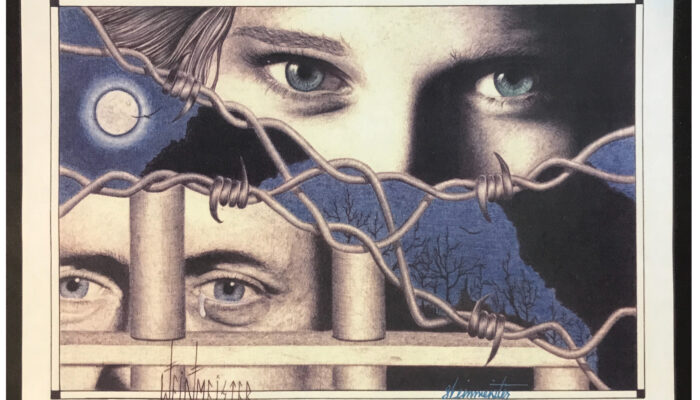

Late autumn, sleepless again, in Dade County prison, acting the part of the hapless white-sand

romantic, singing

bossa nova through the bars, diverting, for a moment, the guard’s attention from a tin tobacco

spit-cup,

he awaits deportation. But why this sentence? The kid’s no capo, no don, no Scarface, no

Escobar.

100-odd miles from the Bay of Pigs & what goes on? An unknown soul singer gets busted

smoking blunts in a stolen car,

then, for a few nights, is locked up. A minor crime, innocuous, even; pitiful by Vice City

standards, no deed of a kingpin.

But let me print this little legend:

One year later, Brazil falls to military dictatorship;

I like to imagine

Tim never flinches under its iron fist, even as the cineastes, the poets, Caetano, Gilberto, his

brethren,

are exiled, jailed, or shot—the lucky ones slip to London, sculpting torch-songs out of fog. I like

to picture Tim,

the scoundrel, O Malandro of neverending street-songs, deported back to the corner, throwing

the shaved dice

of discontent, acting out the gnarled, sly resistance of an exile in reverse. Protected by his so-

called only vice:

“I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, I don’t snort, I don’t cheat…

but I lie.”

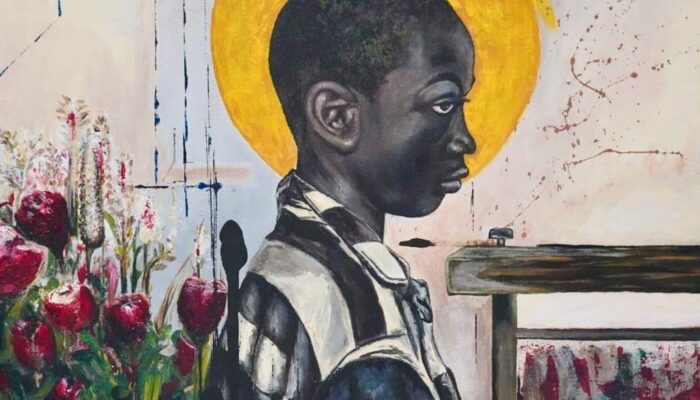

In Orient Heights

Up at Mary’s shrine, with loudspeakers, floodlights, & security cameras perched between angel

statuettes on the wall;

up the 88 steps that cut through flaked-paint triple deckers like a concrete vein, with full view of

bridge, beach,

& financial district, where incoming planes dip down, nearly slicing their stomachs on the

perfectly symmetrical

spikes of her crown; Latin prayers on rusted plaques, signs for Sunday mass in Spanish &

Portuguese.

Up here, purity means the plastic bottles, broken glass, & fast food bags, avalanched &

standstilled on the hill, never—unlike

the snakes she squashes—touch La Virgen’s feet. Peace means I can’t hear the blue line’s

rumble, 1A

traffic, or Todos Jueves: Noche de Rock en Español, the karaoke that sounds like crying. Up

here, a block

removed from the thoroughbred track where racehorses no longer run, the faded gold leaf of her

feet, hands, & face,

that once-opulent fleshtone, the loose-coiled clay of her robe, its aged copper gone green, the

solid brass

sphere she balances on, & the thick steel rod that holds her in place. Up here in the Heights,

between peace

& quarantine, Mary, mother of God, eyes the mainland from her vantage—from the Roman

grandeur & the trash—

lodged in the frontal lobe of my neighborhood: between the landfill it was built on & the heaven

beyond its grasp.