Crosshairs

The first time I spend the summer in Iraqi Kurdistan, my aunt Parween assures my mother that it’s safe – it isn’t like America, she says. My mother nods and hums her understanding, but later, back in America, laughs when she recounts the anecdote. Both women go on believing they live in the safer of the two countries.

What I know of Iraq as a child is learned from the way my teachers respond when I tell them my dad is from there. Oh, they’ll say, jerking their heads back in space as if to put physical distance between us. From Iraq? they’ll question, uncertain if they’ve heard me correctly.

I turn 14 and watch bombs explode over Baghdad in night vision green on the TV in my basement. I am old enough to grasp that the city is so distant that it is nighttime there, though it is daytime where I am. Despite this, the neon green gives the scene a simulated feel, like laser tag or video games. Still, it is intimate to watch, like looking through the peephole on a hotel door. Later I’ll learn about the history of televised wars. At the time, I get the same feeling I got when I watched the twin towers fall. A shifting of the ground beneath me; a lurching towards a different landscape.

Soon the whole world disapproves of the war, everyone but the Kurds, who were gassed by Saddam, their villages bulldozed and burned. The Kurds are arguably the only group that benefits from the war, which plagues the rest of the world long after the troops pack up, leaving a vacuum of power, a wound that will fester.

Kurdistan, a land of Bush-lovers, flourishes. Five years after the bombs fall my family plans a trip to visit the non-country where my father grew up, where my grandfather lives. I stay for the summer, having fallen in love – half with the mountains and tiny cups of tea and newfound cousins; half with just the idea of it. I love the feeling of being in a place so dangerous and far from home. I love the feeling of being inside the cocoon of my family’s compound, its green lawns secured by cement blockades and Pesh Merga holding guns.

The spring before I graduate from college, a frenzy of protests ripples from Egypt to Iran. Governments topple. An alum of my college returns to speak soon after being released by his hostage takers in Libya, where he’d been covering the Arab Spring before it turned into the Arab Winter. In front of a small but packed auditorium of aspiring journalists, he is stiff, his answers rote and inflectionless. It is easy to imagine the trauma. I have already begun to skip classes to read the news, spending hours in bed watching and re-watching YouTube clips of terrible things: mobs of men surrounding women in Tahir Square and assaulting them, soldiers opening fire on protestors in the city where my Kurdish family lives. I decide not to move to Kurdistan after I graduate.

Instead I move to Newark, a decision received with a chorus of concern. I move into a high rise apartment with three other women from my AmeriCorps program, one of whom is so afraid of the city where we live that she had taken self-defense classes in preparation, which she confesses to me while pinning up pictures of her boyfriend back home in Michigan on the wall above her pink bedspread.

That February, Trayvon Martin is shot by George Zimmerman inside a gated community in Florida. Zimmerman is released soon after he is taken into custody and is only arrested six weeks later after the nation erupts in protests. Zimmerman is acquitted, and four years later, will try to sell the gun he used to kill Trayvon on eBay. That spring my students hang up signs they made out of construction paper and markers. RIP Trayvon, the signs read. Why’d he kill him? My students ask, and I tell them, I don’t know.

In June three men approach my roommate outside our apartment and punch her in the face, knocking her to the ground. They steal her iPhone, her boyfriend left hanging mid-conversation.

She lies to our students about how she got a black eye. She tells them that she fell. She stays in Newark for another year. I move to Brooklyn.

Hurricane Sandy starts as a warm spot in the Atlantic, turns to a Category 3 Storm and plows through the Americas, destroying homes in Cuba and Haiti before filling the street outside my Brooklyn apartment with floodwater. The neighbors and I snap photos of it as it creeps up the pavement. Seventy-one are killed in the US, and the worst hit neighborhoods are poor ones, but the image that makes the front pages is of Manhattan at night, dark from 34th street down.

In Coney Island, the school where I have just begun teaching fills with water. The boiler in the basement is irreparably damaged, and won’t be replaced that year or the next. Sand dunes crisscross Mermaid Avenue and a city bus is jackknifed across two empty lanes. I bike down – the trains won’t run there for weeks to come – and survey the damage. I take a picture of a big white SUV propped up on a mailbox before a man looks at me in a way that signals I should leave.

The next day I return to volunteer with the Red Cross. I go door-to-door in the housing projects that tower above the beaches, a mile past the last stop on the subway. The elderly and disabled are trapped inside their apartments, unable to walk the ten or twenty flights down the dark stairs to the mud-smeared lobbies, where the water lines are shoulder high. No water, no power, no heat.

A woman volunteering with me sneers and says this place is ghetto. Says she wouldn’t come here at night. I defend it, tell her that I know kids who live here, but she won’t be moved.

In one of the long windowless halls we navigate with flashlights, my beam illuminates the white outline of a human skeleton hung on a doorframe, and my heart pounds before I remember it is nearly Halloween.

When I describe the damage weeks later at Thanksgiving dinner, my cousin Andy is dismissive. Wow, he says. People were stuck in their apartments without heat! Really rough.

He’d served in Baghdad with the Marines, and now sleeps with an automatic rifle underneath his mattress, so I stay silent, wary of the hierarchy of suffering.

A few weeks later, twenty schoolchildren are shot at Sandy Hook, sixty miles from my school. I turn off the news I normally play in my homeroom that day, and later, we practice the new drills put in place based on the assumed risk. I learn the difference between shelter in, soft lockdown, hard lockdown. I learn what to do when the code rings out over the intercom: Mr. Jones is in the building. Mr. Jones is in the building. Turn off the lights. Lock the door. Shepherd my students out of their desks, away from the windows and into the corner, where we crouch in the dark, spilling into the coat closets, waiting for the drill to end.

Over the course of the next year my relationship with my boss erodes. He sides with a student who writes DYKE on my whiteboard, and my weekly meetings with him start to leave me dizzied and angered and teary. I quit the job, buy a ticket to Paris.

A week after I arrive, a man I’d talked to on the Metro follows me home, taking a back alley and appearing just as I catch the gleam of the glass doors to my rented apartment. I fumble with the passcode but make it inside before he gets to me. I hold my body against the door as I watch him approach and wait for the click of the automatic lock to seal him out. When it does my limbs flush with released fear. I hide inside the stairwell because I am too afraid to go inside my apartment, which now feels like a trap.

I ask the usual questions: had I been too friendly? Was it what I was wearing? Did I give the wrong impression? Was it my fault? No, no, no, no.

I spend a whole day alone in the apartment, afraid to leave, but when I do, I go to a hair salon. I am scared, now, to speak in my broken French. I use my hands to show how short I want my hair and I close my eyes until the sounds of scissors stop.

While I am cutting off my hair in Paris, ISIS rolls through Syria and into Iraq. The journalist who I’d seen speak three years earlier – James Foley – is beheaded, his execution filmed and posted on the internet. The pundits blame Bush for destabilizing the region a decade earlier. ISIS captures Mosul, the second largest city in Iraq.

Plane tickets to Kurdistan – usually prohibitively expensive – drop precipitously. I mull over the situation. Tickets are cheaper, but at what cost? How do I evaluate the safety of a place I hardly know? What is it that threatens me? The plane ride? ISIS? Suicide bombs? I consult maps, news, family. I google kidnappings in Kurdistan. Eventually, I buy tickets.

I arrive in a place that is both changed and the same. I drive by a TGI Fridays 40 kilometers from an active ISIS frontline. I go out with my cousins and her friends to a Mexican restaurant called Titanic and take tequila shots. We hide the shot glasses when someone they know walks in.

Kurdistan is safe – if you have enough money; if you follow the strict social contract; if don’t disobey your family or wander into the warzone or live in one of the cities that fell to ISIS.

When I return to the West, I take a train from Montreal to New York and am asked the following questions while the train is halted at the border.

Are you healthy? How much money do you have with you? Why were you in Canada? You went there alone? Where are you going? Where do you live? Why were you in Turkey? What was the purpose of your trip? Why were you in Iraq? You have family there? How long were you there for? Where did you go? Did you cross any borders? Who paid for your trip?

I am questioned twice by two different officials and both times I suppress giggles and an urge to make a joke about not joining ISIS, filled with the feeling I’m lying and they’re acting, all of us going through the motions of the roles we’ve been assigned.

It’s invasive, all the questioning, but when the train chugs to a start, and I know I passed the test, I feel a sense of accomplishment; a sense of belonging.

Freedom ain’t free, they say, in support of the war, in support of the guns. I can protest this, but meanwhile, all around, the machinery of safety churns onward, and we let it. We pay our taxes. We keep our money in the big banks which fund the pipeline gouging through sacred land. We submit to the small humiliation of being touched by a stranger while we hold our arms up like a cactus at the airport, our belongings turning see-through under the digital eye of an X-ray. We slow down when we pass the police on the shoulder. We proffer our IDs when we’re prompted, step back from the painting when the guard motions us to, and wait two hours in line to ride the roller coaster at Six Flags.

Amusement parks are extremely popular in Kurdistan. New ones pop up outside of town each year. There is Dream City and Family Fun and Freedom Park and Chavy Land; there are small ones that appear and disappear on the dusty street sides, ephemeral and nameless. They fill up on summer nights, when the temperatures dip to a bearable balm, with families and teenagers and couples who walk side by side but not hand in hand. When the power zaps off, as it often does, no one but me flinches. Everyone else is accustomed to the regular blackouts. They do not assume, as I do, that something bad is about to happen, and nothing bad does happen: the lights blink back on. The rides power up. The music begins again.

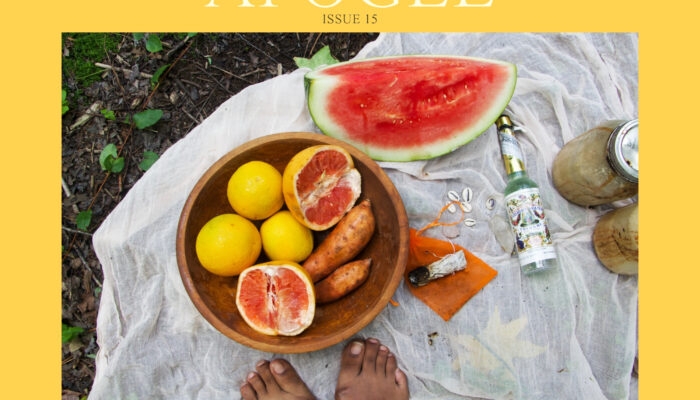

Featured photograph courtesy of Tracy Fuad.