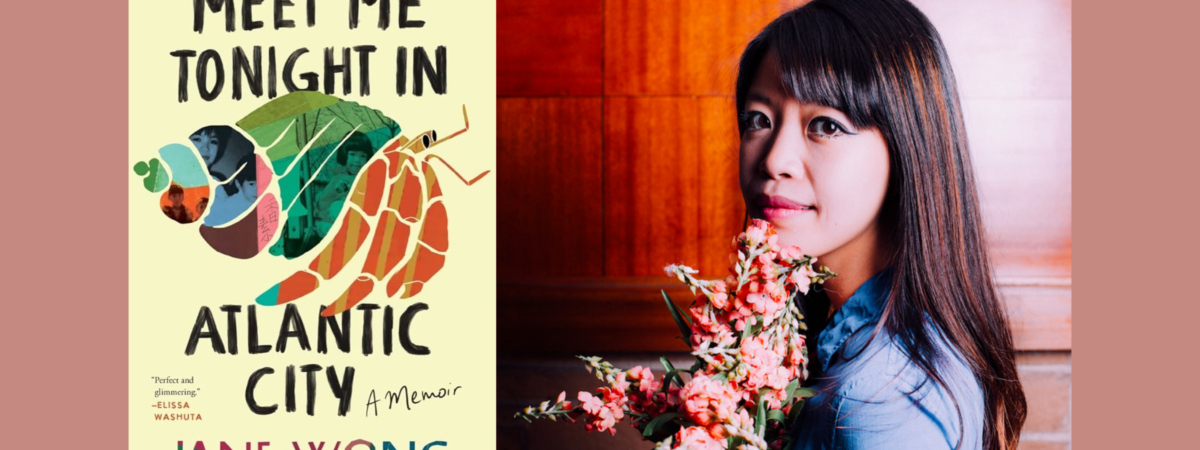

Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City, Jane Wong’s tender and fierce debut memoir, uses poetic lyricism and humor to create a living archive of her family history and a love letter to the mother who raised her and the communities that sustain her. The book is punctuated with short sections outlined in black entitled “Wongmom.com,” which imagine Wong’s mother as an all-knowing advice-dispensing website.

On a sunny summer day, we met up to talk about fruit, maximalism, interdisciplinary art, and combining rigor with play.

Ally Ang: What’s nourishing you lately?

Jane Wong: Summer fruit! It’s cherry time so I’ve been eating lots of cherries and blueberries. Summer fruit, friendship, and finally being able to rest after an intense spring on book tour. I’m in summer vibes mode. I feel like there aredifferent versions of myself—during the school year I’m so focused on teaching. Summer Jane gets to wake up late and actually gets to sit and have a cup of tea or coffee. Summer Jane is the Jane that’s writing or doing ceramics. I don’t really create that much during the school year; I’m devoted to teaching and my job is kind of intense. During the summer, I feel lazy in a good way, a little more floppy. I’m a big pool noodle in the summer.

AA: Before we get into your memoir, I wanted to talk about your ceramics work because that seems to be a big source of joy and play for you lately. What drew you to ceramics and how has it informed your writing?

JW: Ceramics has taught me so much about failure and the ability to be a novice at something–and how to imbue my poetry with that novice quality. Clay feels like poetry: it begins with mud and becomes something with an actual form. I’ve been bewildered by the craft of clay—learning how to slab build, how to slip and score—and that’s very similar to thinking through lineation and musicality. That said, I feel like there’s more failure in pottery than there is in poetry. Things can break, or the glaze may not turn out the way you want it to. I needed to learn how to fail more.

In terms of writing, these days it’s much more about creating something interdisciplinary with different textures. I hope the memoir is textured and has elements beyond what we expect from nonfiction, and I want to achieve something similar with clay. My ceramics and writing haven’t crossed quite yet, but I dream of doing raku firing, where I would make a vessel and then throw my hair in and rip up some of my books and put them in there. That’s my next dream: to find a studio that does raku firing.

AA: You’ve done several interdisciplinary projects where you eat your words, so to speak—like the project where you cut out parts of your poem onto rice paper and folded them into dumplings and ate them, and for the memoir, instead of a traditional unboxing video, you did a “souping” video. What draws you to this practice of eating your writing?

JW: Play and delight and surprise. It’s like revising, completely re-visioning what the poem can mean. I feel tied to giving another life to whatever I write. For instance, with Wongmom.com, it was always my plan to make her real. I’m in the process of making Wongmom.com right now with my friend Eric Olson, who’s a software architect. It’s going to be one of those old-school, early Internet, GeoCities type of sites.

As a person who creates things, I’m always trying to get back to my 10-year-old self. I’ve always been obsessed with play and rigor, which are the two main concepts of my entire being—not just in my creative life but in my teaching as well, and in being a person in the world.

AA: Is it a spoiler to ask what you envision for Wongmom.com?

JW: I’ve been working on this idea with my friend Eric, who’s also very playful. There’s going to be an AOL kind of chatbox. We’re not going to fully AI Wongmom.com because I’m a little scared of what she’d become. She answers questions with lines from the book, things that my mom would actually say. Eric’s idea was that there will be hidden Easter eggs that you can hover over throughout the site, nods to the book. For instance, the chapter “A Jane by Any Other Name” talks about how my name sounds like a goat screaming out of a barn after it rains, so when you click the “A” in the chat box, you see an image of a goat screaming.

AA: Has your mom been consulted in crafting any of the responses?

JW: She definitely has been, but I want them to be even goofier than anything she’d say. They’regoing to be randomized: if someone says, “Hello,” there are a few possibilities for what Wongmom.com might say back, but if you ask a more complex question like, “Should I break up with the person I’m with?” I don’t know what she’ll to say! None of it will be completely made up, unless something goes deeply awry and Wongmom.com starts to have a mind of her own. When I told my mom about this project, she said, “I’m the real mom”–as if she’s going to battle the fake mom.

AA: Your work is maximalist in terms of imagery, lyricism, and syntax, and in your insistence on not flattening your memoir into a single palatable immigrant trauma narrative. Even your fashion is maximalist. What does maximalism offer for your writing and life?

JW: I’m a total maximalist in a time of minimalism, like with Marie Kondo and the #cleangirl trend. I’m creeped out by minimalism that’s an attempt to clean and clear and declutter. It’s always taking away something. That whole aesthetic is not me.

My maximalism comes from an immigrant background. It comes from not having a lot growing up and figuring out ways to make a lot out of what you have. To be an immigrant baby is to be maximalist in some ways. I don’t believe that less is more. If I want to keep riffing off an idea, a word, I’m just gonna keep going.

I noticed that someone named their Goodreads review “Too many pearls,” like there’s too much going on. I keep coming up against, “The non-linearity is difficult,” or, “It’s too verbose, too poetic.” And I’m like, great! That’s exactly what I wanted. I don’t want to pare down my narrative. Our stories aren’t meant to be easily summarized; the book ultimately had to be maximalist. In many ways, it is resisting the current. I feel constantly pressured to minimize my craft and my style, even my pedagogy and teaching. Some professors are like, “She does too much in the classroom.” But I get it all done, and I texture my classroom as I texture everything I do. A lot happens in my classroom in an hour.

AA: And I feel like maximalism is a way for marginalized people to take up space. The whole world is trying to minimize us!

JW: Right! Especially in fashion. To be maximalist in your style is to say I’m here and you’re going to look at my pants and think, “What is she wearing?” I took up that space in your mind.

I think about this a lot with my mom and her style. She came to the U.S. and had an arranged marriage with a stranger; she didn’t speak English at the time and she was coming from communist China. She expressed herself through style. She took up space, she was loud, she was bold. Her outfits then and now are her way of saying, “I’m here with a lot of joy and I get to choose what I like. No one else gets to choose what I like.”

AA: The chapter “The Object of Love”–in which you explore your experience with domestic abuse and gendered and racialized violence, as well as how the love of community sustains you–feels so central to the memoir. What was your process in writing that chapter, and how did you decide on the structure of breaking it into many short, subtitled sections?

JW: If there’s one chapter I’m the most proud of, it’s definitely “The Object of Love.” It was the hardest one to write. The seeds of it were planted in 2014. At the time I couldn’t even publish excerpts because I was so afraid that I’d be stalked. My poetry books don’t explicitly talk about domestic violence or physical and verbal abuse, so it was scary for me to actually write that chapter and tie it to larger questions that I’m currently going through. That was the other risk I took: writing up to the current moment. A memoir is supposed to be a very closed genre that takes place in the past—memory, memoir—whereas I tried to move it as close to the present and questionable future as it could be.

“Astonished Enough” and “The Object of Love” were closer to the end of the actual writing of the book. Because it was coming from such a vulnerable place, I wrote it in little chunks over a long period of time. Whenever I felt emotionally ready to write, I wrote these mini-flash pieces. I wanted that chapter to be propulsive. I wanted to feel like it was moving quickly and that your heart was beating quickly while reading it. Terror is propulsive; it moves quickly through your bloodstream. The structure was my attempt at making these little bits that felt like they were going, going, going.

A lot of readers, by the time they get to that chapter, may have thought that the book was going in one direction but then there’s a volta, a turn. The beginning of that chapter literally directs you toward the turn and says that this is not only a book about intergenerational trauma or a restaurant baby narrative, I also get to write about my experiences of domestic violence. I wanted to make the expectations of this book transparent.

I knew I had to write this chapter but I didn’t want to retraumatize myself. I’d have placeholders—I’d literally write in yellow highlighter, “Not ready yet,” and I’d have to sit for four years before I could write that scene. Even though the chapter is propulsive, it was written over many different periods of my life.

AA: If you had to describe each of your books as a fruit, which fruits would you choose?

JW: Overpour is when you get some blueberries and there’s one squishy blueberry at the bottom of the carton, and you’re eating all these fresh blueberries and you throw this squishy, rotten one into your mouth but you’re fine with it because the other ones were so fresh and juicy and sweet. Overpour is the rotten, squishy, deflated, not-so-delicious blueberry.

I’m obsessed with How to Not Be Afraid of Everything in terms of its color. I wanted the color to be deep, intestinal pink, like organs. Fruit-wise, I’m going to go with papaya—obviously because of the color, but also because my mom makes this soup from unripe papaya and there’s a different flavor to the fruit when you eat it that way. There’s something about the versatility of the papaya in the savory soup versus the sweeter, softer ripe papaya.

Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City already has so much fruit in it. The obvious answer would be mango or dragonfruit, which are the bookends to the memoir. But I’m going to go with tomato, which a lot of people think is a vegetable. There’s one chapter, “Finding the Bloodline,” where I talk about making tomato and egg. There’s something about a tomato in its ripe pulpiness that makes me think of blood. Tomatoes are thick and the memoir is thick, literally! This book is a big ass tomato.

—

Jane Wong is the author of Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City (Tin House, 2023) and the poetry collections How to Not Be Afraid of Everything (Alice James Books, 2021) and Overpour (Action Books, 2016). An associate professor of creative writing at Western Washington University, she grew up in New Jersey and currently lives in Seattle, Washington.