Kemi Alabi’s Against Heaven (Graywolf 2022) is a debut poetry collection both brilliant and beautiful, practicing a deep care for both the speaker and the reader in its pages. Through forty-one formally inventive poems, Alabi writes a Black queer and trans body politic—linguistically exciting and rigorous while still full of care and abundance. The collection encompasses erasure, lyric verse, double golden shovels—a poetic form where the start and end of each line, read down the margins of the page, make two other existing poems or excerpts of text. To quote “Love Letter from Pompeii,” the book “melt[s]/while it still feels good/to scream.”

Alabi, an Apogee contributor who I met at Tin House Summer Writers’ Workshop several summers ago, spoke with me via email about Against Heaven, its goals, and its form.

—Zefyr Lisowski, Poetry Editor, Apogee Journal

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Zefyr Lisowski: There’s such a profound vulnerability and expression of love, care, and pain in this collection—I’m thinking of “The Lion Tamer’s Daughter” sequence and your “Eulogy for the Voice in My Head,” but also, in a more tender valence, “Love Letter from Pompeii.” How do you sustain that vulnerability as you write? How do you take care of yourself?

Kemi Alabi: I find vulnerability really pleasurable, but that’s not where I usually begin when I write. I’m always playing with sound, trying to find the line, and letting language lead me somewhere. I’m satisfied with what I’ve found when the real shit pops up, and that’s what I can revise toward. Black feminist writers taught me the urgency, political potency, and transformative power of truth-telling, and the only truth I’m interested in is accessed through vulnerability—I’m skeptical of its other origins. So I don’t consider this a volatile place to write through. It’s a space of aliveness and relief.

ZL: Following up with that, what’s the relationship between self-care—in the encompassing, radical meaning of the word that Audre Lorde originally meant when she wrote it—and poetry for you?

KA: Self-care would make me a better poet. Unfortunately, I struggle to care for my body and mind on a basic level, and I come from a long line of people who’ve been forced into self-neglect through racial capitalism. It’s hard for me to write when I’m unwell, and I’m frequently unwell. This country makes me unwell. I know some people can write through illness or burnout or their other responsibilities. Some people find writing therapeutic. For me, writing is an essential way of being, so caring for myself includes protecting time for the practice. But for me, poetry is a difficult craft and largely unpaid labor. I think that’s why I end up carving out so much vulnerability and tenderness on the page—I don’t think I’ll become a prolific writer, so the poems that do get written need to be truly felt. But to access feeling, if I’m following Lorde’s understanding of self-care, and even though poetry is absolutely not a luxury, I first need decent sleep and some quality healthcare.

ZL: The collection as a whole emphasizes pleasure—queer, polyamorous pleasure—amidst everything else. I remember at Tin House we talked about the importance of adrienne maree brown’s Pleasure Activism to you—where else does pleasure manifest, in your writing or elsewhere?

KA: I love that Pleasure Activism begins with Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” Against Heaven begins with an epigraph from that essay:

“The erotic is a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings. It is an internal sense of satisfaction to which, once we have experienced it, we know we can aspire. For having experienced the fullness of this depth of feeling and recognizing its power, in honor and self-respect we can require no less of ourselves.”

Pleasure informs both the craft and content of my writing. I love the pleasure of poems, particularly their sonic delight. I think my work will always be shamelessly lyrical and ecstatic. It might always prioritize music over meaning, though my current craft concern is finding the clarity between those poles. On a content tip, I know our political systems demand our estrangement—from Earth, from one another, and from ourselves. Pleasure and the erotic, as explored by Lorde and many of the Pleasure Activism contributors, is a route toward reconnection. I used to call myself a brain in a jar with pride. I couldn’t identify what felt good and what felt bad. I couldn’t feel my needs and wants. I couldn’t feel my yes and no. I thought knowledge was objective, a cerebral pursuit. I was very loyal and useful to systems designed to exploit and discard me. I think pleasure can get a bad rap as hedonistic escapism, but Black feminist thinkers revealed it to be a route toward re-embodiment. Re-animation. And as Howard Thurman once said, “Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.” This isn’t painless or escapist by any means. But from a pleasure-awakened feeling and aliveness, the systems controlling us reveal themselves to be death cults. Their authority cracks. And for the sake of true aliveness, care, and connection, the only conclusion is that they must be completely destroyed.

ZL: What’s the significance of the double golden shovels for you? What can they do that other poetic forms don’t necessarily? What’s your relationship to lineage, citation, and formal constraints in your writing more generally?

KA: Double golden shovels are fun! I love the opportunity for an intertextual conversation, and I love the challenge of creating within its container. In the collection, most are used for title poems—the borrowed language helped me arrive at new arguments “against heaven.” I knew I resonated with or was repulsed by the borrowed language, and writing within and against it helped me discover why.

The golden shovel, as created by Terrance Hayes, is specific to Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry, but I’ve yet to complete a golden shovel with her words. I’m holding the tension between honoring these Black poets by respecting the original golden shovel rules…and my rebellious desire to break and remix a received form (which also feels like a Black art practice across time and genre). I call my poems golden shovels instead of acrostics for two reasons: Hayes’ invention helped reveal the meaningfulness and possibilities within that type of formal constraint, and Brooks’ poem “To the Young Who Want to Die” feels like an ancestor to many of the poems in Against Heaven. One day I’ll pull off a golden shovel with that one.

More generally, I love a formal constraint to play within and against. Knowing the structure helps me focus on the line, so form is something I like to understand about all my poems as I revise, whether it’s a received form or not. Regarding lineage and citation, I’m always reading toward and searching for potential literary ancestors and elders. I think all writers are expanding and deepening and reflecting and resisting the language before and around them, and citation is a practice that helps one stay conscious of that. I’d like to be more rigorous about it.

ZL: I’m so taken with the multiple valences of writing against heaven—both in being “ungoverned by the lie” as you write in one of the titular poems–but also, as you quote from Belinda Carlisle, in noting that heaven is a place on Earth too. What does writing against heaven mean to you? What lineages of writing against heaven exist for you?

KA: I also love the layers of meaning. On the most literal level, some poems oppose the idea of heaven as an out-of-earth afterlife. I don’t believe in the concept, and I find it socially harmful—both because it props up myths of innocence and guilt, and also because it estranges humans from this planet in ways that diminish both life and death. It may be easier to be against hell, this idea of eternal punishment, but what does it mean to reject both the idea and the desire for a perfect post-life peace? How does that remake one’s living? How does that move the sacred from a gated elsewhere to right here on Earth? And what kind of care would that demand?

Of course, that idea of heaven isn’t the only one, but it dominates our culture—as do myths of purity, perfection, goodness, innocence, objectivity, order, and so on. So what does it mean to reject those myths? What would it mean to embrace complexity, uncertainty, mystery, mess, chaos, disobedience, and so on? Which systems would become senseless? What exploited, repressed power could (re)emerge? What social identities, which are power relationships, might fade? What knowledge would be (re)discovered? Would distinctions between high and low art, good and bad art, disappear? Could a poem be anything? Maybe writing against heaven means a wild thrust toward radical possibility, ruling law and order in the rear view. This is what so much incredible Black art does.

ZL: Is there a poem or a part of the collection that was especially hard for you to write (in a productive or generative way)? Hard for you to write (in a frustrating way)? Easy for you to write (in whatever way you’d prefer to interpret that)?

KA: Maybe this is cheating, but the final poem—and by that, I mean the long poem that is the collection—was the hardest to write. Ordering the poems was a trip and a revelation. I learned so much. This collection didn’t begin as a project book, and I wanted to honor the through lines of my work without being linear. I wanted to introduce structure without imposing neatness. I wanted to push together themes that others might separate. I hear and trust the long poem, the fall and underworld journey, that is the book—every poem is placed where it is for a reason, even if those reasons seem opaque. But these were difficult decisions, as I know people love clear narratives and hate confusion. Some people have asked what led me to write about race and gender and sexuality and religion and and and, implying that these things are separate! It might feel more coherent to them to have distinct sections where all the X, Y, and Z poems go, or to remove contradictions, or to say it all plainly. Again I think of Audre Lorde when she said, “There’s no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we don’t live single-issue lives.” Again I think of music and meaning and where I land. I wanted everything to live in a complex mix with complex rhythms, like it does. If you get whiplash sometimes, good. So do I. If you can’t make it make sense, just stay for the music.

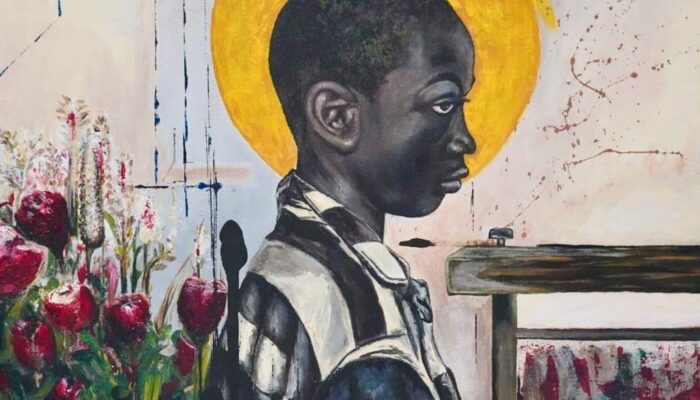

Kemi Alabi is the author of Against Heaven (Graywolf Press, 2022), selected by Claudia Rankine as winner of the Academy of American Poets First Book Award, and coeditor of The Echoing Ida Collection (Feminist Press, 2021). Their work appears in the Atlantic, the Nation, Poetry, Boston Review, The BreakBeat Poets Vol. 2, and elsewhere. Born in Wisconsin on a Sunday in July, they now live in Chicago, IL.

Zefyr Lisowski is a poetry co-editor at Apogee Journal and the author of Girl Work (Noemi Press 2024), winner of the 2022 Noemi Book Prize. Zefyr has received support from Blue Mountain Center, Tin House Summer Writers Workshop, and elsewhere, and her poems and essays have appeared in Catapult, The Offing, The Rumpus, and beyond. She grew up in the Great Dismal Swamp, NC, and currently lives at zeflisowski.com.

Portrait of Kemi Alabi: Toya Beacham