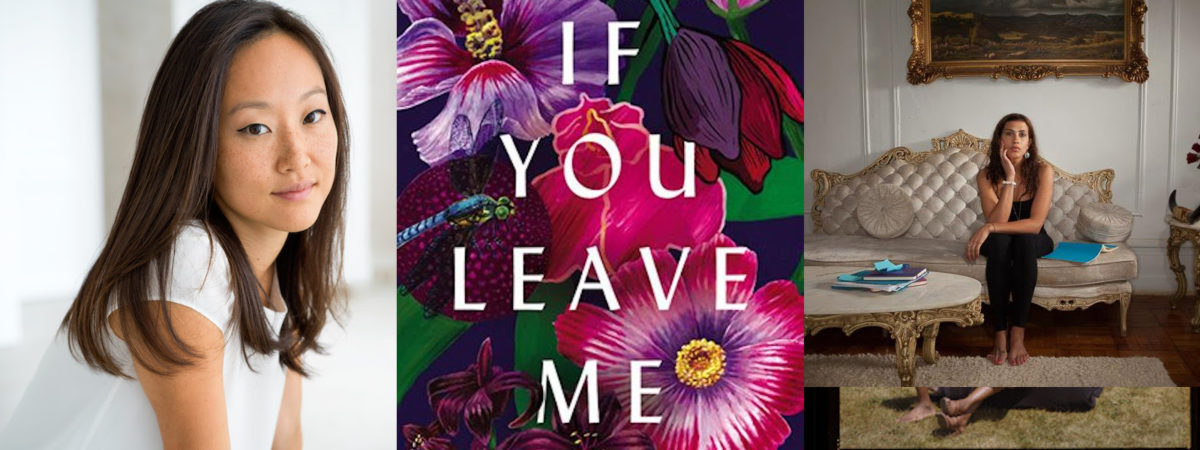

A conversation with Crystal Hana Kim

Propelled by a riveting love story, and informed by historical context, If You Leave Me explores the Korean War and its aftermath from the perspective of the ordinary people who endured it. Kim’s novel centers the experience of a woman who comes of age in the midst of violence, displacement, hunger, and illness, which shape every relationship in her life. If You Leave Me is both gentle and fearless; innocence coexists with taboo. The novel’s insistence on listening to what women think, and what they feel, is mirrored in its author’s approach to research and the writing process. Apogee’s executive editor, Alexandra Watson, spoke with author and Apogee nonfiction editor Crystal Hana Kim about the genesis of the book, and its themes.

Alexandra Watson (AW): You’ve had a lot of interviews and conversations about If You Leave Me! What questions keep popping up?

Crystal Hana Kim (CHK): A lot of people have asked me about my research, because it’s so steeped in historical facts, and not a lot of people know much about the Korean War. They want to know what kind of background I have. A lot of people have also asked about what surprised me in the research process. I like that question. I keep returning to the same thing: What surprised me was that there was so little information about women during the Korean War. Nobody cared about women’s roles. They weren’t soldiers, they weren’t valued, they were secondary during that period of time. In retrospect, it wasn’t surprising at all, it was just disappointing.

AW: You seem to have captured personal experience in intricate detail—did you use first hand accounts?

CHK: I read two memoirs of Korean soldiers, one of whom was North Korean, the other of whom was South Korean. The North Korean soldier had escaped and come to South Korea later on in his life. Because I couldn’t get primary sources about women, I supplemented by interviewing my grandma and aunts. I also started looking into psychological studies done on Korean women, like on the way that they’ve responded to trauma and depression. In Korea, even now, therapy and depression are not talked about openly.

AW: When you were interviewing people, especially your family members, were they at all reluctant to share?

CHK: My maternal grandmother was not. We’re really close, and she knew I was working on this project, and she loves to talk and tell stories, so she was really open. My paternal aunts were also open, but I had to keep asking questions. I didn’t ask them as many personal questions, because it was a group interview, with all the aunts who were alive during the war in one room.

AW: In general, do people in Korea talk openly in public about the war; do they reminisce about it?

CHK: Lately, the war has been in the news in Korea a lot more because of the Inter-Korean Summit that happened in April, and Kim Jong-Un, but I don’t know how often it’s just part of the conversation. I know a lot of Korean-Americans who live here have reached out to me to say they’re excited to read the book or that they felt very moved by it because their parents or grandparents wouldn’t talk about the war.

AW: It must have been a challenge to negotiate the tension between what you could find out from your research and what your characters would have actually known.

CHK: That was really important to me. My fear is always explaining too much, because I don’t like books that have a lot of exposition. Since my novel is all written in the first person, I wanted to be in the characters’ heads. I needed to make sure the information I provided about the Korean War and what was happening politically was something my characters would know. During the editorial process, my editor said, “You need to provide more context about the Korean War because readers may know very little about it.” It’s called the Forgotten War here for a reason. That was challenging, but in retrospect, interesting, because it was like a puzzle. I had to figure out what Haemi would know as a young teenage female refugee. What would Jisoo, who’s a little wealthier and has gone to high school, know? I had to think of the reader, then include information based on what the characters could tell the reader.

AW: You had really clever strategies for that. Like the radio that the boys go to listen to during the lunch break. That felt totally narrative—it was exciting that they got to go do that. It also worked to give us more context.

CHK: The characters talk a lot about the rumors they have heard, because there was no definitive news that reached them during active warfare, especially in those rural areas. And some people were illiterate, like Haemi’s mom, who was born to a rural, impoverished family. So it’s a lot of hearsay and gossip. But I was hoping that by hearing snippets, the reader could get a sense of the news surrounding the war.

AW: And then Haemi also gains more insight as the book goes on.

CHK: In the beginning, Haemi doesn’t know much about what’s going on. She’s so young, only sixteen. And later on in the novel, she’s thinking back on the war and what she knew back then versus what she now knows. So I think the reader is growing and learning with her. In the beginning, the characters are teenagers, so I wanted their personalities to feel like teenagers, and have them mature throughout the book.

AW: That’s such an interesting thing about the first person. How little each of us really understands about these big social events or processes, and how you balance that with the need to convey context to a reader.

CHK: A lot of people during the time didn’t know what was happening. It was just commotion. The war started when the North attacked the South. It was a complete surprise. It took a while for that information to trickle down, then everyone was fleeing, but no one really knew what was happening. It’s so strange because now we’re in such a connected world, where you get too much information all the time. It was interesting imagining myself in these characters, and how little they would know, and how scary that would be.

AW: In the wake of all of this commotion and upheaval, I love that the book starts with a celebration. What does it mean for you to locate joy in this world?

CHK: I want to convey that life continues during war. You have to find joy even in the hardship. That’s what a lot of people would be striving for or seeking. That’s what my grandmother told me. I wanted to start with this idea of a celebration to show the hope. I’m exploring difficult themes about womanhood and motherhood and war and trauma. I wanted there to be moments of levity for the reader. You need an emotional break.

AW: I felt that. It was deeply intellectual, but a page-turner. I don’t know if anyone has directly called it a beach read, but I’ve heard people say, “I read it at the beach.”

CHK: That’s so interesting. I think it’s because it came out in August. But it’s a little heavy to be just a beach read.

AW: It’s a pleasurable reading experience. It reminded me a little of some of Chimamanda Adichie’s writing, where war can be a part of everyday life but also a backdrop. It’s not as harrowing as something like The Handmaid’s Tale, where I kind of had to take breaks from the brutality of the book. Some writers seem to want to tap into a psychological darkness, which isn’t how I felt about this book.

CHK: That’s good. I wanted it to be realistic, and have weight. But I also wanted it to have moments of levity and pleasure. Moments of joy. I didn’t want it to be just bleak. And sexuality…

AW: It’s sexy!

CHK: I especially wanted to focus on women’s sexuality.

AW: Romantic relationships are so compelling in storytelling. The lovers and their fate… that’s something that keeps me turning pages.

CHK: It feels gendered to me, the way that books by women that have a love interest at the center are labelled romance or thought of as cheesier or lighter than books by men. In my MFA thesis workshop, that’s something that I expressed concern about—that as a young woman writing about love, if I leaned into the love story, people would want to market it a certain way or think of it a certain way. And Ben Metcalf, my thesis workshop teacher, said—look at all the epic stories of our time. They all have some sort of love story. The English Patient, Anna Karenina. These big books. So that made me feel better. At the same time, I think as a woman writer, I’m always thinking about that way of categorizing women’s books about love as ‘just a romance.’ There’s nothing silly about love. We’ve just been influenced to think about women writing about love that way.

AW: Haemi’s yearning seems just as much for her own self-actualization as it is for any love interest.

CHK: I think so too, it’s about self-actualization and independence and freedom. For Haemi, Kyunghwan represents freedom and independence and a different sort of life, more than he is her only interest.

AW: Speaking of driving forces, hunger and food play a big role in this book. Haemi’s yearning is for self-actualization later, but at the beginning, her primary goals are treating her brother’s terrible cough, and getting food. The scene where Jisoo brings a whole chicken is so powerful! What was it like to write about hunger?

CHK: I grew up hearing my grandmother’s stories about the war, and the stories that stood out to me most were always the ones about her hunger—looking for food, or eating food, or wanting food. Even my parents—they grew up in the fifties and sixties in Korea, but it was still a pretty impoverished nation, and the stories from their childhood that stood out to me were the ones about searching for food. My dad told me this story once, which made it into the book, about kids coming to school drunk. Elementary school kids! There was some kind of distillery, nearby the school. And so they would go there in the morning and eat the lees—the sludge leftover from making the alcohol—because they were so hungry. They would come all red-faced to school. Those stories in my research stood out to me. Wanting food is universal, and I wanted to convey the characters’ hunger and how important food was, and that it’s a central motivating factor for them.

Kyunghwan has this tick of eating one noodle at a time—eating slowly, because he’s so hungry.

Food is a great way to transport the reader to a different culture and different time. We’re familiar with it, but different cuisine or dishes can help the reader feel immersed. I’ve heard from other readers that they wanted to eat after reading this.

AW: I found myself craving anchovies and pepper paste for the first time ever. Kyunghwan’s fishy, spicy mouth becomes appealing!

CHK: Right? You wouldn’t think fish breath would be appealing, but when you’re hungry, it is.

AW: The way you present men’s camaraderie is really interesting. I’m thinking about when Jisoo is unsure whether the fighting has come to an end and whether he can go home yet. He’s around all of his military friends, and their joking and banter feels very much like an inside view of boy’s club. Did that perspective come from the memoirs you read?

CHK: I think the memoirs helped with being able to effectively convey the male perspective. Haemi, Kyunghwan and Jisoo are so isolated. Jisoo is isolated from his family. Haemi is isolated because she’s a strong willed woman in a time when that’s looked down upon. Kyunghwan is isolated because he’s essentially an orphan. I wanted them to have community sometimes. It’s a novel about a woman, but I wanted the reader to get a strong sense of how the war affected different people. Jisoo is best at creating this community—he’s a man who always has a strong group of friends and is actively trying to rebuild his life. Also, in college, all my best friends were guys—I was around that kind of camaraderie a lot. I think it’s interesting watching the way that boys interact with each other when there aren’t a lot of girls around. So much teasing and joking.

AW: The dialogue had that feel! At the same time, there’s a sense of the conversations and knowledge that’s intimate among women. One moment that stood out to me was when one character thinks about a type of plant known to induce abortion. It seems like even in traditional societies, there’s a secret knowledge that gets passed among women. I was curious about those questions of women’s knowledge, especially around reproduction and reproductive agency.

CHK: I wanted to write about a woman who was grappling with her agency and whether or not she wanted to be a wife. My family is made up of a lot of very strong women. My mom is one of five daughters. They’re all very independent and different from one another. My grandmother survived the war as a teenager, she had to marry someone for security, she wanted an education and didn’t get it, she divorced. She was a divorcee raising her daughters at a time when that was not acceptable. I’m lucky enough to be surrounded by really strong women.

I wanted to write about the ways that women have secret coded languages among them. Kind of like how we were talking about Jisoo and the way men were acting around other men, whether that’s joking or bravado. I also wanted to explore the way that women support each other during this time, and the type of communities and networks they have. I know there are certain herbs that can be used to provide women with agency, but I think that even back then, it was looked down upon to not want children. With every birth, there’s the desire for a male.

AW: The secret life of women can disappear from the cultural memory.

CHK: I wanted to explore the knowledge women have that’s passed down from generation to generation. It’s the women who would come to help when you’re pregnant. I think that’s totally relevant still now. What actually happens during motherhood is not talked about openly. A lot of friends who have given birth have told me, “I had no idea that this happened. I had no idea that after you give birth you’re still wearing a diaper.” There’s so much secrecy, and I think that that’s a problem. In one way, there’s something powerful about this knowledge that’s passed down. But the fact that it’s so hidden is a problem too.

AW: I was curious whether the Korean language changes the way you think about writing in English. Was the prose influenced by the cadence, the type of vocabulary, or syntax of Korean?

CHK: The Korean sentence structure is totally different from English sentence structure. Sometimes I would think about the sentence in Korean after I wrote it in English. Sometimes in the description I would try to capture what it would sound like in Korean, or how would someone alive during this time in Korea describe the world, what kind of metaphors would they use, and what would be the cultural contexts they bring in when describing?

AW: Haemi’s mother looks tall and skinny like a mahwang plant.

CHK: And even certain metaphors, I would think about how I could weave them into the narrative without italicizing. I didn’t italicize the Korean words, because italicizing makes the word look foreign on the page. It others. These are Korean characters, so they wouldn’t make their own language foreign. I think that italicizing used to happen more in older books, but I think that trend is changing.

AW: It would be like “makgeolli, a rice wine.”

CHK: Right. Without the explanation, the reader can still get it, maybe not right away, but maybe a few times later, from the context. I think we can trust the reader more than people thought in the past.

AW: If You Leave Me covers a long span of time—decades. How did you decide when to pick back up with the characters, and were there other false starts in that process?

CHK: At first, I wanted every chapter to be one moment in a year—so I wanted one chapter to be 1950, the next to be 1951, and so on. I was trying to map it in this rigid way, but I realized that it was stifling the narrative, because I was trying to force it into specific time periods. I didn’t know how to write a novel at the beginning.

Another rule that I imposed was that every character would get the same number of chapters. And then I realized, after talking to Stacey D’Erasmo during my thesis conference, she said, “You’re the author, you can do whatever you want—don’t feel so held down by the rules.” And I was like, “Are you sure? I feel like it’s not fair to give Jisoo another chapter at the end.” She said no, it doesn’t matter—it’s your story, let yourself be free of these rules you’ve created for yourself.

So then I went back and created a timeline of big moments in Korea’s history, because I wanted to at least have someone reference when there was a dictator, or when there was another election or a major student protest. I knew I wanted to touch upon those events, but besides that, I really let the characters drive what chapter would happen next, who would speak next, and what year it would be. So it was a lot easier once I let go of my own restrictions.

AW: We get this message as fiction writers of—you’re creating this world, so you have to establish what the reader will expect and then follow through on all those expectations. But no novels that are interesting actually meet your expectations exactly where they are.

CHK: I had a lot more fun once I stopped following the rules, because I was thinking—won’t the reader be confused or annoyed if it’s not one year after the next? But as long as the story is good, the reader will follow you. Once I realized that, the chapters became much more character-driven, because I just had to decide who should tell this part of the story and why. That was a lot more fun for me, because I like writing characters.

AW: I was so emotionally attached to your characters that I was sad it ended.

CHK: That’s the kind of book I like. I also care about sentence level beauty. For some books, you can tell the author’s goal is to be funny or to explore a particular intellectual topic. My main goal is for readers to emotionally connect with the characters.

AW: The yearning does that for me. Unfulfilled yearning, which is so true to life. The things you want to happen in the book… I’m not going to spoil anything, but you want so badly for Haemi to be able to explore something different. And then there’s something so small as Solee ripping up a note that makes things not happen that way.

CHK: I wanted to explore the way that these characters desire so much, but a lot of it, they can’t have or follow through with, because of the circumstances of living during these turbulent times, or of being a mother or a woman, or being uneducated—there are all these other forces that prevent them. There’s that tension, what they want and what they can’t have.

AW: It’s counter in some ways to this American ideal of, “If you keep striving for this thing, it will happen.” Or your life will somehow turn out to be a manifestation of everything you kind of always wanted. Which is not the case.

CHK: This is a realist novel in that sense. Kyunghwan does everything—he studies, and he tries, he works hard. He works at a paper factory. And he still can’t really determine how things end up for him.

AW: When Kyunghwan starts to sell beauty products, it seemed like an interesting precursor to the current huge industry around Korean beauty products. In what ways do you see the events of the novel setting up the ethos and logic of present day Korea?

CHK: The first is political. Right now, Korea is all over the news because of the conversations between North and South Korea. In order to understand what’s happening now, especially because Trump met with Kim Jong-Un, and the president of South Korea, Moon Jae-in, met with the North Korean leader for the first time. In order to understand what’s happening now, we have to understand the history. Fiction is a good way to understand not just the facts, but how it affected people’s lives. So, I’m hoping the novel is a way that people can empathize more with Koreans. We’re so inundated by news, that it’s easy to read about war and devastation and just move on. But when you’re reading fiction, you care about the characters. You care about what happens to them, and the facts of the war become realized.

Culturally, it’s so interesting that Korea is having this moment internationally and in America: K-Pop, Korean skin care products, Korean barbeque. It’s so weird to me because growing up, no one knew anything about Korea. In New York, my classmates would know about China and Japan, but not about Korea. What’s astonishing to me is that sixty-eight years ago, when the Korean War started, Korea was a completely impoverished country. After the war, it was completely devastated. And it’s rebuilt itself so fast. That’s really fascinating, to see how a country in ruins has become part of our cultural consciousness in such a big way.

AW: American media representation of North Korea paint it like a sci-fi, surreal, almost like everyone living there is inherently attached to the government’s isolationism and control. Your book helps remind or teach an American reader how arbitrary many peoples’ fates were. How people ended up on one side or the other.

CHK: Totally arbitrary! It’s really just happenstance where you were. If you were along the border and you got captured by the North and you were separated from your family, you would never see them again. My husband’s grandfather, who’s Korean, never saw some of his siblings again. He happened to be on the South Korean side, but he was from the north. It’s heartbreaking. The media makes North Korea seem like a completely alien place. They make North Koreans look like robots and dehumanizes them. That detaches your ability to empathize.

AW: And what about women’s roles in society? What does feminism look like in South Korea today, in your perception of it?

CHK: The “Me Too” movement has also taken off in South Korea, and started a dialogue about sexual harassment and assault. That’s become a big part of the national conversation recently. It is a place that’s patriarchal and socially conservative, but the conversation is changing.

AW: What’s going on with your next book?

CHK: Right now, the next project is set with a Korean-American woman in present-day America. Her narrative alternates with a Korean man in South Korea in the eighties. It’s really new, so it keeps changing. I’m excited!

Crystal Hana Kim’s debut novel If You Leave Me was longlisted for the Center for Fiction Novel Prize and named a best book of 2018 by The Washington Post, ALA Booklist, Literary Hub, Cosmopolitan, and more. Kim was a 2017 PEN America Dau Short Story Prize winner and has received scholarships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Hedgebrook, Jentel, among others. Her work has been published in Elle Magazine, The Paris Review, The Washington Post, and elsewhere. She is a contributing editor at Apogee Journal.

Alexandra Watson is a founding editor of Apogee Journal, where she has helped secure grant funding for community arts projects from the New York State Council on the Arts, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and Brooklyn Arts Council. She teaches essay writing and literature of the Americas at Barnard College. Her fiction, poetry, and interviews have appeared in Nat. Brut., Redivider, PANK, Lit Hub, and Apogee. She’s a graduate of Brown University and Columbia’s School of the Arts.