An Interview with Poet Evan Cutts

Last week we featured three poems by Evan Cutts, a 23-year old poet from Boston who has a remarkable way of using language to, as he expresses, “re-claim and re-contextualize,” systems of power. In his four-part poem, “Grahamstown Sequence”, which is an account of the #QueerToStay “Take Back the Night” demonstration at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown, South Africa, Cutts describes the experience of taking part in a demonstration to “disarm the night”—an act which ultimately takes place through protest in the form of human connectivity.

In our interview, we discussed language as protest, how to demonstrate more effectively, and allowing the space for magic to enter a text.

—Mina Seçkin

Mina Seçkin: Your poems—specifically “Encounter with Black Magic” and “A Hunting Tale”—explore black magic in an incredibly unique and powerful manner. What role does black magic play in your poems, particularly while in conversation with issues such as systemic racism and violence?

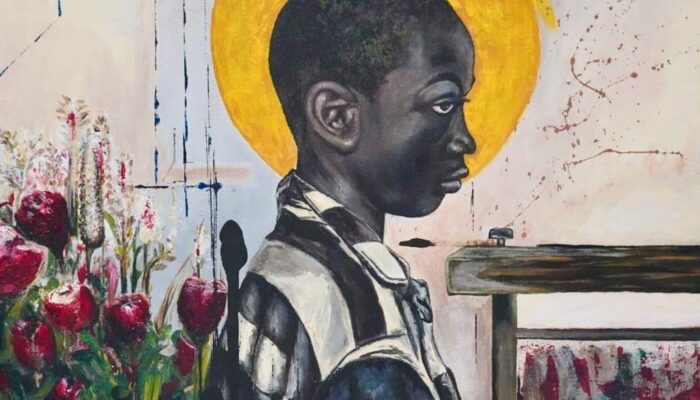

Evan Cutts: Black Magic plays a two-fold role in these poems. I aimed to evoke a playful spin on power within the idea of Black Magic as a form of reclamation and re-contextualization. You know, adding a mythical attribute to our legacy of excellence, cultural production and influence, survival, and resilience. Black Magic also has its negative connotations as immoral, demonic, ungodly. My hope was to repurpose the term as a weapon against such unethical and immoral acts such as enslavement, genocide, and perpetuating racial prejudices. I like to think of this as building from the history of African and Afro-diasporic religious and spiritual practices which were tools of resistance, self defense, and self preservation.

I started exploring the roles it could play in my poetry at Porsha Olayiwola’s “Black to the Future” Afro-futurism, sci-fi, and magical realism workshop at VoxPop last September. Have you heard of it? VoxPop is an annual open-invitation spoken word tournament hosted by Slam Free or Die in Manchester, NH. Individual poets and pick-up teams sign up and compete for two days—it’s a great time.

One of her prompts was: list up to 3 ways you identify yourself, write a story where one of those identities is attacked and a magical consequence occurs in response. I chose ‘Black’ and ‘Voice’ thinking about the six years (6-12th grade) I spent, in part, being called an Oreo in the Brookline Public School system because I was often perceived as talking/acting/dressing/etc. “White.” With some regularity I was told that I “articulate myself so well,” that “I wasn’t like other Black People,” that I simply “wasn’t Black”—even by some of the Black students. This is not a new story. Until I was given the option to rewrite the story.

The original draft was in 3rd person about a boy named Kyle (me). I thought, what would be a funny and satisfying way to resolve the exchange? To turn the people who claimed me to be something I wasn’t into the very thing they othered me as. It was one of those rare poems that really wrote itself. The edits I made amounted largely to inserting “I”, tightening the syntax, and finding a form I liked.

MS: Your meditation on the “I”—the insertion of a short but powerful word that means so much in questions concerning identity—reminds me of how “Grahamstown Sequence” unfolds. The structure seems to spill loose throughout the Take Back the Night demonstration and the “I,” introduced in the beginning as falling into line “behind a dozen hands holding cameras focused on the man leading the procession,” dissolves by the second half of the poem. How did this poem-in-sequence come to life? Did you know the structure and shape of this poem from the beginning?

EC: Thank you. Being a part of that demonstration was a really surreal and moving experience. I was clueless about the focus or the mission for a little while and even knowing the general impetus for the demonstration I had no idea how it would all unfold. I wanted the sequence to reflect that sense of unknowing, curiosity, and surprise. What brought the sequence to life I think was, firstly, the event itself. Mind you, I learned after the fact that the exchange between Sthembile and the individual in black, the lanterns, the blades, their dance and exchange of power, was staged. In the moment, I was lost in wonder trying to understand exactly what was being communicated between them and the audience. Secondly, there was a drive in me to retell this story. I wasn’t sure how to tell it in a way that was more than just a narrative account. That is, until 2 or 3 weeks later at the end of a Winter Tangerine summer workshop. The lesson of the week was to introduce the absurd into our writing. Specifically: write a narrative non-fiction piece, but switch the end for the surreal.

That’s how, what I would call the magical, enters the sequence in the last two poems. I felt then I had a way to poeticize that experience in a way that grounded my perspective as a witness, while also giving the necessary space to communicate their transformative performance, exchange, and message.

This is all to say, I didn’t know the exact structure but in my initial recounting of events to my classmates, I noticed distinct turning points in the story: discovering the march, the emotional pause on the corner of Prince Alfred which was concluded by the hug and photo, followed by our arrival, and then, the ceremony which I feel is appropriately named “Revolution” because of the political nature of the demonstration, but also because promoting love in the wake of violence is a revolutionary act, it’s also a magical one in the way it provides healing, safety, community, and dialogue.

MS: It is a truly revolutionary act, as you express, to promote love in the wake of violence. What you mentioned about allowing the surreal into the end of a piece reminds of something Maggie Nelson once said, where she mentions leaving a space empty to allow God to rush in. In this case, perhaps the word “God” is “magic.” I find that your work repurposes what is broken in society, what is very violent and unjust, into magic, into a connectedness.

EC: A quote for a quote: “Everything is near and unforgotten” – Paul Celan. This quote introduces Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam and is something I think about often. There is a connectedness within many of our experiences, that connection is often what builds communities. That construction of love in the wake of violence and injustice is a force of magic, one that creates space for life, change, and our voices.

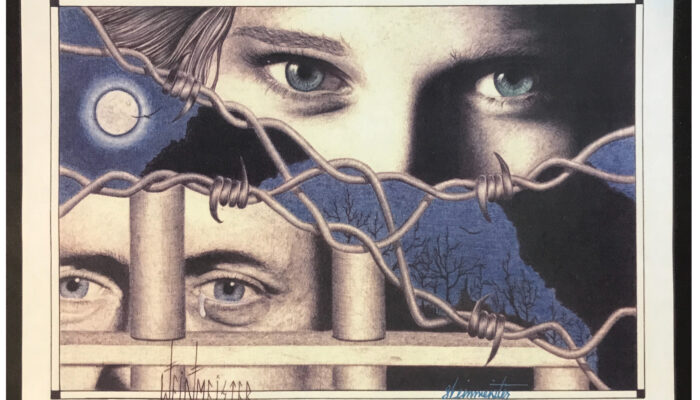

MS: The last line in “Grahamstown Sequence” was deeply moving, and I loved how it was obscure whether it’s the crowd or humanity as a whole who is “disarmed,” then “follows.” Can you speak to the ending of this poem? As you ask, What’s left? How can we demonstrate effectively, and how can words be used as protest?

EC: The ending to this poem was one that I struggled with. I wanted for a long time for the message behind it to be speaking to more global issue of humanity enacting and perpetuating violence against ourselves. But initial drafts obscured that message because of the way I first gendered the “shade-being.” They were femme presenting that night, so they were written as “she” in the poem. The last poem relies heavily on pronouns. The issue I had was the “he/she” dichotomy. The poem is also trying to reflect the importance of deconstructing binaries that limit our perceptions of love, gender, sexuality, and more. It felt contradictory to have the final half of the poem default to the gender binary. When I realized I could directly insert Humanity as a metaphor for the “shade-being’s” presence the poem opened up and I could write the ending I intended.

What was left for me was certainly the story. Specifically, the image of Sthembile reaching for their hands, blades and all. When they met, eyes locked, they lowered together to a knee. In that moment, I saw something unspoken move between them. It was a connectedness, I think, an understanding that a truce was declared. What’s left for me is the symbolism with that moment: the willingness to face the night, the blades, death, and broker a deal to walk away not just with our lives, but our sense of self, our identities, proud and defiant.

Of course, the world we live in doesn’t often clean itself up so nicely. I think a value of poetry however, is to imagine and communicate how such endings might look and to offer an idea or an instruction on how to carry oneself in that direction.

I think to demonstrate more effectively, we should continue to incorporate the arts into our demonstrations in new and innovative ways. Art in its many forms engages people, prompts new ideas, challenges perspectives and sheds light on untruths and mis- conceptions. There’s so much power in language, it’s why the N-word is dangerous; it carries a history of violence, of dehumanization. The same is for other slurs. The power of language is also restorative, this is evident in how slurs are reclaimed by the communities whom they were used against, in how we take pride in the names we’re given and give ourselves. When I think of language as protest, I think of naming and context. There’s a passage in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, where the question is asked, what makes language hurtful? It is answered: our addressability. Language preys on being able to locate us in our physical bodies, to which is attached our identities, histories, perceptions of ourselves and other perceptions of us. The n-word is a slur used to dehumanize Black people, and it receives its identifying context on our appearance. When a history of violence and unequal racial power dynamics are attached to the word, it carries that history and plants itself in a physical point that we (non white-passing Black poc) can’t remove ourselves from: the features that identify us as Black. So my question, which I don’t have an answer for, is how to remove, or disarm, that context that gives certain “names” such terrible power? Yes, there are the reclamation movements but those only go so far. Can we galvanize the language of resistance further? I’m not sure how but that’s a direction of exploration my writing will be venturing into.

MS: You mentioned that your poem “A Hunting Tale,” wasn’t quite finished until your recent trip to Cuba. Can you speak to this experience? How did you know when the poem was finished?

EC: “A Hunting Tale” is a poem I wrote after learning of Freddie Gray’s murder. It began with what was until recently the last line of the poem: find me another “n-word” who thinks himself free—kill ‘em.” I was struggling with a discomforting sense that “freedom” at times felt more mythical concept than anything tangible or secure. It expressed a harsh reality, that safety for us, and not just us, isn’t guaranteed. I brought the poem to the College Union Poetry Slam Invitational with Emerson College this year. It went through a lot of editing to be ready for those stages and though I felt pride in being able to share my truth to receptive crowds, friends, and poets something didn’t sit right with me about it. I realized what it was the day I read your email, Mina. Our class was spending a few days in the city of Trinidad. The trip for that day was to visit a defunct sugar plantation and discuss the legacy of enslavement practices in Cuba, which lasted into the early 1900s. Following the news of its publication it felt incredibly urgent that I read this poem at this plantation. That’s when I realized I couldn’t read a poem there or anywhere else where the embodiment of white racism wins, where we die. So, in the few hours I had between lunch and our visit, I wrote the last section of the poem introducing magical realism at the exact point where I, we, needed a miracle—something to affirm that our resistance and resilience will serve us beyond the boundaries of such a limited and violent worldview.

My professors and classmates were kind enough to give me the space to share “A Hunting Tale” shortly after we arrived at the Iznaca family plantation, which was restored as a restaurant, with no memorial or recognition of the land’s bloody legacy. I performed the poem at the top of a stone watchtower in front of my class. There’s a video of it being edited at the moment. I finished writing the poem minutes before reading it. The reclamation of our lives, the denial of death and the violence of white supremacy signaled to me the completion of the poem.

MS: Wow. I’m moved by your description of that day—what seemed like an immensely powerful and informative, as well as emotionally challenging, day. There’s something I can’t name or explain, something spellbinding when place, history, and words align in one day, one hour, one reading, to produce art.

EC: I think reading “A Hunting Tale” there is an example of that connectedness we spoke of earlier. Art, history, and location all came together in an attempt to reconcile the violence of colonialism and enslavement. I wanted a chance to rewrite the narrative and I am honored that my class provided space for me to do just that and listened. There’s a power to that which you aptly named “spellbinding.”

MS: Speaking of being moved, who are the writers and/or artists you find most inspiring?

EC: Writers who are really inspiring me to write more poetry, and begin to find avenues for my essays, are Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib, Sasha Banks, Jose Ramon Sanchez, and Victor Fowler Calzada. Hanif’s work continues to impress me in the way his vulnerability and honesty touch down on the familiar rhythms of Black pop-culture before catapulting into his cathartic yet heartbreaking reflections on the struggle and joys of being Black in the U.S.

Sasha Banks, a Pratt Institute-MFA candidate, is doing phenomenal work interrogating the US’ legacy of systemic racism and violence, reasserting the presence of Black women as agents of resistance to that violent legacy, as well as consciously re-imagining the future of the “American experiment.” A future that asks what would the world look like if white supremacy ceased to exist? Who will survive the collapse of the American empire? What and how will they rebuild? If I haven’t said it already, imagination is a key component to envisioning a future that sincerely values the immense diversity (of culture, experience, identity, etc.) that exists in our country, and the world.

Jose Ramon Sanchez and Victor Fowler Calzada are two Cuban poets whose work I spent some time studying in Cuba and are very new to me. Victor Fowler, a writer since the 80s and publisher of 10 collections of poetry write much about body, race, sexuality, disability, poverty, and empire in revolutionary Cuba. Jose Ramon Sanchez, co-editor of the Cuban lit mag La Noria is currently writing a collection of poems entitled Gitmo which are focused on stories of the naval base, from or about the prisoners who have been imprisoned there, and its political symbolism as a lasting marker of US imperialism encroaching on the island of Cuba. Jose Ramon is a poet and co-founder of the Cuban Objectivism movement which seeks to write poetry that is grounded in local realities. As such his recent work is focused largely on location, the naval base and the city of Guantanamo where he lives. Victor Fowler engages with location in a similar way, I find. Both of these poets are producing art that aims to examine life before their eyes and question the factors and forces which produced the experiences in front of them. This conversation, in specific poems, “Malecon Tao” (VFC) and “La Cerca es Infinita” (JRS), creates this exciting phenomena of a metaphysical transcendence of place and history, which I think might be (insufficiently) described as seeing the trees in order to envision the forest. Though not the best analogy, I can say I’m writing an essay on their poetics which do a better job of articulating this fascinating style of writing.

MS: I love the work of Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib as well, and I’m excited to read Sasha Banks, Ramon Sanchez, and Fowler Calzada. Also I’m very much looking forward to your essay on their work!

EC: Yeah, if I can tack on someone else to the reading list: Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam. As for my essay, thank you! It’s an ambitious project for me, and one that hope extends a platform for more conversation on contemporary Cuban poets. It’s about half-way done now and I’ve a lot more to say. When it’s done, I’ll make sure to send you a copy. If not sooner. I appreciate questions and critique when I can have them.

MS: I’m excited to read it. My final question for you: what do you hope poetry—yours and others’—can do?

EC: My hope for poetry—mine and others’—is that it continues the work of beginning necessary conversations, making space for unheard and undervalued voices and perspectives, building communities on respect and accountability. Poetry gains so much and gives so much through its accessibility to the masses. So, I hope poetry continues on its current trend and distances itself from the ivory tower. I struggle with this hope however as a poet who has the privilege of learning about poetry in the ivory tower and in the dive bars and basements of Greater Boston. It is a self-driven responsibility, I think, to bridge the gap between these spaces. Naturally, I fear that I might not succeed in this effort and I appreciate the people in my life who help me keep a clear and focused mind on this mission.

And though it is difficult to do in such seemingly hopeless times, I want my poetry to also operate as a conduit for joy, resilience, and a kind of honest beauty that raises a smile to my reader’s face.

Evan Jymaal Cutts is a 23-year-old Boston native, poet, freelance writer, and writing workshop facilitator. Evan was a member of the Emerson College 2017 CUPSI Team. He puts his faith in Black joy, his mother, and the collective power of imagination and empathy. His poetry navigates expressions of Blackness, Boston, heritage, and magic. His first collection of poetry, Encounters and Other Poems, was self-published this year and can be ordered online here (x) . His work can be found online at Three Line Poetry, Voicemail Poems, Maps for Teeth, and The Merrimack Review.