Apogee contributor Justine el-Khazen reflects on how and why she writes, in conversation with nonfiction editor, Safia Jama. Her essay “Hummingbird Effect” is so lyrical and it might be mistaken for a poem, yet the rhetorical rigor and form extends the boundaries of the essay. You can read Justine’s piece in Apogee Issue 08.

Safia Jama: Where do you tend to do your writing? Feel free to think literally—as in physical space, tools—or, figuratively, as in, the places you travel to in your mind…

Justine el-Khazen: I’ve tried to cultivate all sorts of generative writing practices, keeping journals, doing exercises, etc., but I’ve realized recently that my writing is very driven by narrative and clear communicative goals, so it’s really research, at home, at my desk or in my bed depending on my energy, that supports my writing, gives it shape. Mostly, this research is done on the Internet. My focus doesn’t have a slow burn, which restricts me to what’s publicly available and those engines that are free. Also, my books are at home, and I fall back on them, on reading the voices of others, when the synergy between my mind and the research is insufficient.

SJ: Your piece, “Hummingbird Effect,” addresses the problem of police brutality with great empathy. Would you shed light on how you wrote this lyric essay?

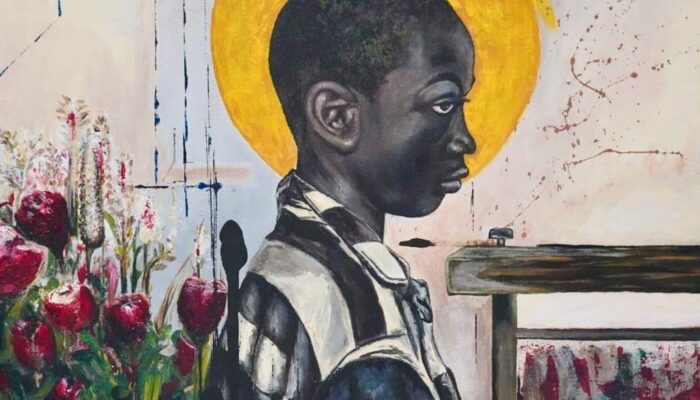

JE: I struggled with that piece for a long time. I felt connected to Eric Garner’s death in some way because he lived and died not far from me, so I kept thinking, but what could I say that hasn’t been said and that would mean something? The more research I did, the more I began to feel he was murdered by agents of the state, and that’s important, but so is just who he was, the memories people had of him. Those details that fit a more personal scale tend to get lost in the narratives we have about police brutality and the political action they fuel. So I wanted to write about that: the loss of his life and what it meant to those who cared about him. Ross Gay’s stunning poem, A Small Needful Fact, was a guide to me in this undertaking; he knows how to weigh loss, Ross Gay. I also watched many interviews with Erica Garner and Ramsey Orta on Democracy Now! I think it was one of their first meetings on television after Eric Garner’s death, and Erica told Ramsey that he was a hero to her family and that they were committed to doing more to support him in his legal troubles going forward. Something about their exchange stuck with me; their grief was palpable. Ramsey Orta is a hero. His face, the sadness in it, his fearlessness in the face of danger and willingness to accept incredible personal sacrifice and injustice in order to do what was right remain with me on some level and conditioned the work on some level too, I hope.

SJ: And, I realize this is a huge question, but I’d be grateful to hear your thoughts on this: how does form and/or genre guide your work?

JE: I’ve had to move away from poetry into prose this last year. Poetry was too fragmentary for what I’m trying to achieve. I need narrative, sentences and voice to be able to give shape to the questions and concerns that drive me, their context, their history and the myriad human details that swirl around them. But I still consider myself a poet because even if I’m straying in form and genre, my approach seems fundamentally poetic to me. I don’t have a desire to transfigure reality in a story or to tell my story. I’m trying to communicate in the most economical and linguistically precise way possible about the world we share. Yet that attempt to establish a connection with the reader on the basis of language alone seems like poetry to me.

SJ: What are some of your Muse’s obsessions, preoccupations these days?

JE: I think for me the greatest challenge is how do I responsibly represent the un-representable, and give a human dimension to situations that have a political-social-historical scale?

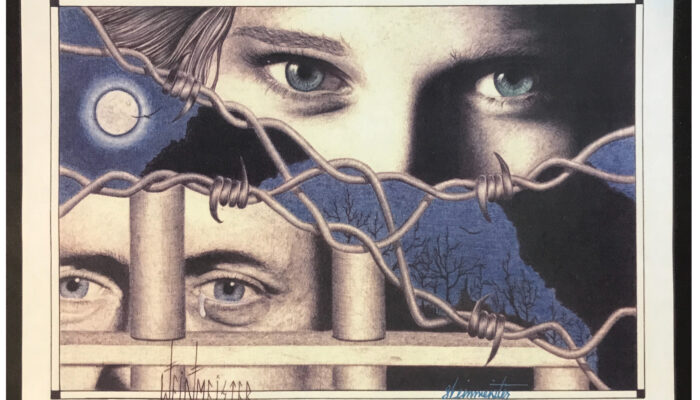

I find Alfredo Jaar’s Rwanda projects instructive in that regard. How crazy and brave to go there within days of the end of the genocide and try, try to absorb what he could, document what he could and create work that would help the anesthetized Western viewers at home to really see what had happened—not listen to the news, not write it off as more African political instability, but see, feel and understand that the unthinkable, what we promised, after the genocides of the Armenians and the Jews, would never happen again had in fact occurred, a third genocide in the twentieth century and one which the United Nations, an organization whose charter demands the signatories cooperate to stop genocide, could easily have quashed; the Hutus killed the Tutsis with knives.

Our indifference reached that level. Hundreds of thousands of people died needlessly. You can’t engage with Jaar’s work without learning all that, but he’s not trying to teach you the political history. He’s trying to render the loss on a human scale, at the level of individuals, details, memories that are more devastating than anything you could read in the news or a textbook. I read that he felt all of his projects were a failure. What matters to me, though, is that he tried, and the example he sets. There is so much happening in our world today to which we are anesthetized, suffering, murder we reduce to data, of necessity.

How could we feel it all? But therein lies the challenge for me. I’m interested in feeling all of it: police brutality, income inequality, debt, healthcare, capitalism, consumerism, the environment, factory farming, the refugee crisis, our million proxy wars, the drone program, Syria, Guantánamo. You have to be a little crazy to live with these things and not go crazy, and I think we all are on some level. How can I unsettle my reader, not bully or wound them, but just unsettle the disposition they’ve taken towards this or that situation? That’s one of the questions I ask myself, and I ask it in solidarity, out of love. That’s the challenge I’ve set for myself, in a nutshell.

For me, the most pressing question of today is: how do we keep the flame of hope alive? We are under siege right now, kind of like in the legend of Hanukkah; so where will the God-given miracle oil that keeps us going come from? I believe we will keep going, that we will break this system that keeps reproducing injustice over and over, though I don’t know how. I want the reader to meet me in a place where we can meditate on the future together.

Read Justine’s story, “Hummingbird Effect” in Apogee Journal Issue 08.

Justine el-Khazen was a 2014 Emerging Poets Fellow at Poets House and a 2015 apexart International Fellow. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Brooklyn Poets Anthology, Apogee, The Cortland Review, The Margins, Harriet and Beloit Poetry Journal among others. She is an Editorial Adviser at VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts.