Your earliest memory is from when you are two years old, when you saw your father beating your mother. You remember very few details about the night, but you remember admiring your mother’s beauty, even then—she wore a red leather two-piece; she had the silkiest ponytail that you’d ever seen. You hear your father screaming at her and your mother screaming in defense. You see him push your mother’s leather laced body against the wall, and then slam her head into it. She drops her ID on the ground, and you are comforted by the smile in her picture, almost forgetting the violence in the background. When she screams, an unfamiliar, yet inevitable, feeling begins inside of you. It’s a mixture of regret that you can’t help her; fear that you’ll lose her to the grip of something or someone; and disbelief that a person would ever hurt someone as beautiful and fragile as your mommy. This emotional mélange will scar you this night, and follow you for the rest of your life. Please be ready for it.

Two years later, you are sexually assaulted by your father. You couldn’t quite call it rape. He kisses your lips and body inappropriately when you are alone together. He rubs places he is not supposed to rub and puts his tongue places on your four-year-old body. You will carry the guilt. Luckily, the shame and self-loathing will become so numbing, so early, you will forget the incident altogether and move on entirely. Well, not really. You will develop sexual feelings for older men with pretty eyes and, maybe in some part of your subconscious mind, your father. You’ll feel connected to things that are taboo, for years, until you finally unlock your truth—twenty years later. You don’t tell your mother. You fear her guilt would come to surpass your own.

By the time you turn twelve, you have been homeless on the streets of Baltimore for two years and are failing the sixth grade for the first time. Your father has finally stopped beating you, your brother Tywone, and your beautiful mother in all her ponytailed glory. Your mother’s drug and alcohol use has grown so rampant that she has taken to sex work in order to feed you as well as her habit. It is another cross for you to bear. Although the trauma from your first dalliance with homelessness will live beneath your ribs for the rest of your life, you prefer it to living with your father. Your body finally starts to heal from the physical bruises he inflicted, but your emotional bruises are just beginning to take shape. This is the year your family gets a house, at last; you fall in love with it.

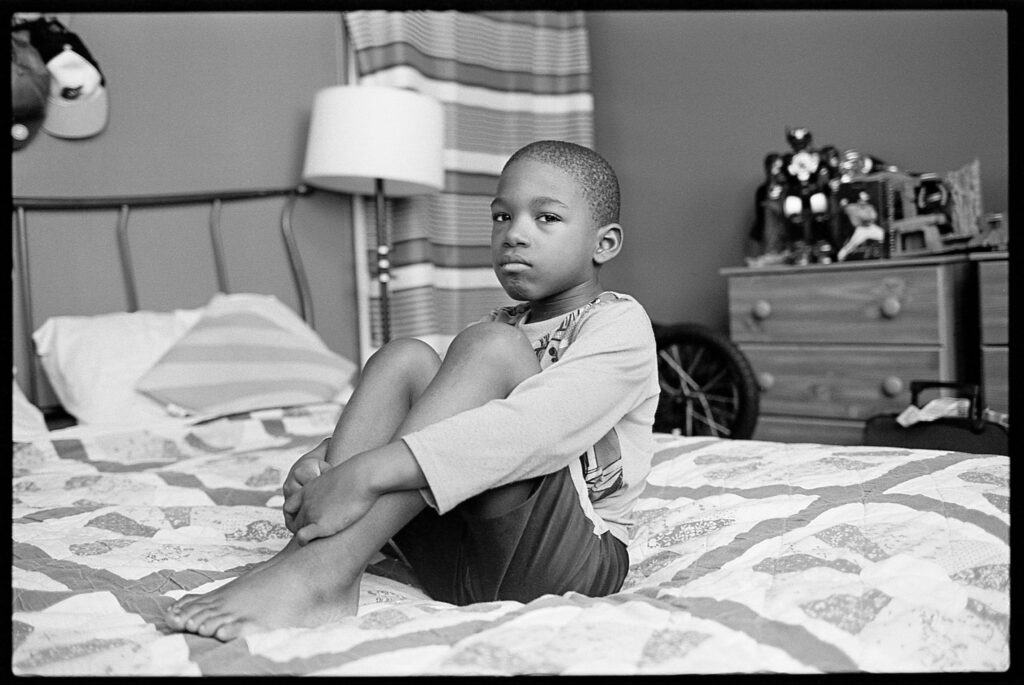

Your brother’s room boasts pictures of Three Six Mafia, the continuous smell of weed smoke, and a two-foot iguana named Rocky. Your mother’s room is classy and minimal. Ivory paint, glass bedside tables, and the smell of lavender pushing into the air. Your room becomes a shrine. Your twin bed sits upon eight discarded milk crates. You tape photos of Aaliyah to your walls and honor her memory with a swift punch to anybody who bad mouths her. You listen to “Rock the Boat” two hundred times a day and hear rumors of an Aaliyah compilation album at the end of the year. On December 10, a beautiful album is released for her, with all new pictures you’ve never seen, but the joy surrounding the album doesn’t suffocate the grief you feel from her loss. Sadly, your grief is just beginning.

The second week of September, 2002, you meet a boy named Kirby. He is sports-obsessed and extremely popular. He is a beautiful boy. You leer at him from your desk in Spanish class and sit close to him in the math class that follows. You shrink in the presence of the attention and respect he commands. It’s the opposite of how you’re treated—being called a fat faggot and sitting alone in the cafeteria. One day, when you’re wearing your brightest, ugliest, and most oversized red shirt, Robert McCormick tells everybody he caught you looking at Kirby’s butt. You deny this truth; he threatens to “fuck you up.” Kirby defends you. Kirby goes against the conventions of his popularity and commands that people leave you alone. The next afternoon, as you’re holding your books tightly against your rapidly forming fat boy tits, Kirby jogs up behind you and formally introduces himself. You don’t look him in the eyes; you are insecure about the dark circles beneath yours, but he is so beautiful. He walks you home and talks to you about your life. You are very quiet and don’t share too much. In front of your door, he asks if he can leave his notebook with you overnight as he goes to play down the street.

The next day you arrive at school, cheeks layered with the rose hue of a little white girl who just received her first kiss. You hold that notebook tightly against your titties, as if to exclaim to the world, this is my man’s notebook. Kirby is mine. All you bitches back up. You quietly slink toward him in the hallway, and when he sees you, he lights up. You spend the day staring at him in class. After school, he runs up behind you again to walk you home.

You have fallen so deeply in love that it’s all you know. You spend most of your free time with him. He comes to your house and builds a relationship with your family. He stays for dinner some nights and goes home late. He smiles at you with his whole face and you always look away—please try to embrace this. Please try to soak it in and open yourself up to it. You know that he likes you, even if you he doesn’t tell you. He does sexually explicit stuff, like slamming your head into his twelve-year-old crotch, but otherwise, you’re both very innocent. He is perfect. He treats you like you’ve never been treated by a boy, as if you are as fragile and deserving of love as you are.

In December, you spend the night that Aaliyah’s new record comes out with Kirby. You sit on your bed playing Uno and learning all the words to her new songs. Aaliyah fills your room with her presence, and you can feel it everywhere. You start to romanticize the idea that you will die at twenty-two as well, as some sort of deeper connection to her. Kirby cuts the edge off one of your Aaliyah posters to make you mad. It’s only a small tiny white corner, but you hit him with the Uno deck anyway. He goes downstairs, then comes back up when he realizes you are really upset. He apologizes with a hug, one of the warmest you’ll ever receive. You stare into his eyes for the first time in your friendship, hoping for a kiss. You don’t get it. He stays for another hour and then heads home.

The next morning, you wake up knowing that something’s wrong. It presses heavy against your chest; it nearly immobilizes you. By the time you get to school you can feel it vibrating in your body—a discomfort, a disquiet. In your second class of the day, where you sit behind an empty desk where Kirby usually sits, you are destroyed by the news. Kirby Hilton-Bey hung himself.

You visit Kirby’s mother, who feels fairly certain that her son would not have spent his free time with a “faggot,” but she won’t tell you this for two months. In the days leading up to his funeral, your very first, you stop sleeping. Your nightmares don’t know the difference between the real world and the dream world. You ride to the funeral with Kirby’s stepfather; you’re the first to arrive. You climb the church stairs alone as his family gathers in the front. You see his obituary and feel your heartbeat slow to a crawl. When you turn around, you see him, his body propped up in his angelic white casket. His body finally his. You don’t cry. You smell what might be Tide coming from the tacky brown suit they selected. You touch his cold hand and wonder why he looks so different. You lose your breath when you see the marks around his neck they tried unsuccessfully to hide. You become weary when you notice his eyes are sunken. You start to worry about where he’s gone and if he is still your Kirby. You’ll never know. You kiss his forehead and accept that that is all you’ll ever get.

You convince yourself that someone murdered your Kirby, though you can’t prove it. You don’t weep until they start to close the casket. A light scream that you try to unsuccessfully stuff back into your mouth escapes. You feel your heart is locked in that box with him. They carry your golden boy to Woodlawn Cemetery, where you won’t visit him for another twelve years.

You will lose two friends this way. Eleven years later, Kirby’s brother will kill himself after their mother dies of a heart attack. A neighborhood friend who knew Kirby and who tells you this will have just lost her baby brother to suicide as well. Although her brother is young when Kirby dies, he will feel Kirby haunting him in the weeks leading up to his death. He, too, will hang himself. You will be ruined by the unshakable similarities.

A few months before you turn thirteen, your mother has a baby girl. You try to get her to name your sister Aaliyah, but she settles on Melita, a mixture of her father (Melvin) and mother’s (Lolita) names. She will be the new love in your life. Your mother’s drug use increases. She stays out later and comes home less. You see more men in and out of the house.

You feel a need to protect Melly. You sleep with her every night, with her clutched in your arms like a chubby little ragdoll. You change her Pampers, and you give her baths. You do everything short of breastfeeding her. She starts to bring joy back into your life, adding color back to your cheeks. One night, your mother is gone—likely out getting high. It’s midnight and you and the baby haven’t eaten in two days. You start to worry about Melita. You ask a neighbor to borrow some food, but he’s high too, and tells you that he has none. You feel powerless. Your older brother comes home and you tell him to watch the baby while you head to your aunt’s house. When you get off the bus and bang on your aunt’s door, she doesn’t answer. You feel like you’ve failed, and you fear that your sister’s going to die.

An older man sits across the street from you, watching you from the stairs. He tells you, “come here,” and you go to him. Somehow, you’re not afraid; Kirby has desensitized you from fearing danger and death. The man, old and rusty, asks what you’re doing out so late.

RUN. Don’t tell this man that you need money for Pampers and milk. Do not follow your mother’s examples. Don’t follow this man into the alley and allow him to touch your innocent body. Don’t let him put anything in your mouth. Don’t let him have your body; your body is all you have. Don’t let Kirby’s death lessen your self-respect. Don’t let your fear for Melly’s tummy allow you to be sold, like a piece of cheap, rubbery steak.

But you do all of these things, and they scar you—at twenty-four, you’ll still cry about it. At twenty-four, you’ll still want to die. When Mommy comes home two days later, she asks about all the food in the house. You tell her that you found a hundred dollars coming from Juan’s block. She asks for twenty and starts frying up some chicken. You’ll never really return from that alley.

Twelve months later, you get evicted for the first time. Your mother has been late on the rent, and her addictions have been gripping her throat like Daddy used to. One morning the police surround your house, and your mother comes into your room whispering. You can see the fear as she perspires, huddled in the corner. You all assume that these are truancy officers because you haven’t been to school in weeks and are failing the sixth grade for the second time. Instead, they are the sheriffs coming to evict you from your “Section 8 property.” They yell through the door. Your mother opens it slowly. They tell her that she has to go to court right away to try to get an extension—the eviction is scheduled for 1 p.m. They warn her that if the judge declines the extension, they will begin evicting us without hesitation.

Mommy tells Tywone to take the baby somewhere else, afraid that CPS will get involved. And she tells you to start packing as much as you can. You tell her you can’t pack the whole house. She squats down, places her hands on your cheeks, looks into your eyes, and says, “Please try.” You see her eyes welling up, and you nod like a good boy. You scramble through the house, trying to pack your things. You start by packing your Aaliyah posters, then Tywone’s room. You’re trying to find boxes and bags to put everything in.

Your family has been declined. You hear banging on the door and see all of the neighborhood crackheads pushing their way in. You go outside in your oversized shirt, Parisian silk head scarf, and bare feet to watch as the neighborhood kids circle. They make a crowd directly across the street from you, and you wonder if they are truant too. You feel like a spotlight is on you, center stage with all your insecurities, loneliness, and shame illuminated. You are being evicted. As a group of men from the neighborhood enter your home they begin taking your life a part. You wonder where your mommy is. As all of your precious things start to line the grass in front of your house, you are torn between leaving it all in search of help or staying to protect it. The crowd of fellow neighborhood truants grows louder. You hear them making fun of your scarf, so you take it off, only to remember that you have some kind of mushy afro braid situation below, which they proceed to mock. The men hired to evict you are not being gentle. As your furniture starts to roll down the hill you hear the kids yelling, “Ahhh haaaa” and “We taking your shit.” You panic and run to a neighbor’s house, a neighbor who you’ve never seen and will never see again. Your mother doesn’t have a phone so you call your grandmother, she is in no position to help you. When you leave their house, your mother arrives with a truck. You are not alone anymore, but you are homeless again.

In 2012, you are twenty-two. You are about a hundred and twenty pounds heavier than you were at twelve, and suffering from crippling depression. You are regularly engaging in unsafe sexual practices with strangers. You sexualize the risk. You don’t care about your body; you just need to feel. The subconscious things you have suppressed about your father and your interaction in the alley have manifested themselves in the dank, lonely spaces of your mind. You are in college, living on your own, and you just lost your job. You have been trying for weeks to find new employment in order to pay the late rent. All of your friends are broke, and you are about to face eviction. You haven’t spoken to your mother in a year. You stopped talking to Aniah, your best friend from high school, a straight boy who you’ve been in love with since the ninth grade. He is written on every breath you take, so your heart breaks every time you breathe in. He can’t possibly reciprocate your love, and you fear you have lost him for good. You are worried that you won’t find the money to save your apartment, that you’ll lose what you worked for two years to keep. You are worried that you will fail this semester due to the stress. All your worries come true.

You move in with your grandmother after you get evicted, reopening the familiar wounds of displacement. Terry, a childhood friend with whom you’ve reconnected, drives you and your things across town and helps you schlep them up three hundred stairs. You feel like you’ve hit rock bottom. You get an email: the college has cut off your financial aid and you are on suspension. You appeal.

People’s kindnesses extend as far as they feel it should, not as far as you need it to. Your grandmother starts allowing your mother to visit the house, and you leave every time she comes. If you would just go talk to her, maybe fall into her arms, she might help save you from the heartache you feel. But you are steadfast in your commitment to stubbornness. You avoid her like the plague, until you can’t. One day, as you toil away in your grief, locked away in your temporary bedroom, you hear the familiar fragility in your mother’s voice ringing through the house. She knows you’re there but respects your wishes to not talk to her. You hear her crying to your grandmother, “What did I do?” and “I miss my baby.”

You stay up all night and compose thirty neatly written letters to everyone that you care to say goodbye to. You leave a page of instructions for your memorial and even designate a music playlist for the service, which is heavy on Feist. You write a letter to be featured in the Towson Towerlight, the student newspaper, about the importance of loving altruistically and the dangers of white privilege and white silence.

On the morning of June 22, when your grandmother goes downstairs to your Aunt Carolyn’s apartment, you go into her bedroom and collect about fifty of her pills. You grab everything, from her lupus pills to her heart medication. You chase the pills with twenty-two Tylenol PMs and play “La Sirena,” your favorite Feist song. You email the letters with instructions to your very best friend Phillip—although you have not spoken in months, you know he will handle this situation with care.

You cry as you start to feel tired. You decide to go downstairs to visit your Aunt Carolyn—she is one of the most important people in your life. You lie on the floor of her bedroom as she and your grandmother talk about the shootings that recently occurred in the neighborhood. The phone rings. It is a frantic Phillip. Your aunt hands you the phone and you hang up. You make up a lie that you were in the middle of a fight, and your grandmother snatches the phone. He calls back and you can hear his voice trembling on the other line. He asks her if you’re all right. Your grandmother hangs up on him. You have to come clean. The disappointment and shame settles on the room, like a plume of dust.

On your way to the hospital, you feel sincere disappointment. You wanted to die. You wanted it more than anything in life. You are repeating your family’s mistakes, everyone that you loved has disappointed and abandoned you, and you are a failure. In the darkest points of the silence, you think about Kirby and how he got out so early, and you think about Aaliyah and that perhaps your death was a few months ahead of schedule.

When you arrive at the hospital, they never pump your stomach. Nothing happens. Your body rejects every pill you took. You feel a bit sleepy in the beginning, but you never even take a nap. You spend the next week in a psych ward. You find no solace or introspective reprieve in this place. You walk around all day, afro unpicked, face sans makeup, barefoot, and empty. They offer you medication, but you refuse. Good friends visit you and call, but you can tell that they are almost afraid of you.

You tell a few lies and manage to get out early. When you check your email, your school has granted your appeal.

Two months later, you have another place and are back in school. A few weeks after that, you learn that your friend and former neighbor Duane has hung himself. Duane was a truly gentle soul, who loved nothing more than being a clown for you and making you laugh. He, too, battled demons. You allowed the distance between you to grow in order to protect your energy. You find out about his suicide three months after his death. You discover that he took his life just around the corner from your grandmother’s house, a week before you tried to do the same. You learn that he left behind a daughter who was only a few months old. The guilt is the pillow on which you’ll rest your head from this day forward.

When you turn twenty-two, you fall in love for the first time. You believe it’s the first time because love has never felt like this before. Diel is nineteen when you meet. He is kind of a nerd and is into photography and videography. You meet downtown at the harbor to swap notes and network. He makes you smile with your whole face. He seems genuinely fascinated by you, which makes you uncomfortable. You see each other every day that week.

You bond so deeply, so quickly, that it almost syncs your DNA. You completely isolate yourselves into your own private world. He moves in with you, and you lose yourself. For three months, he is the only thing that matters. You are open and honest with him, but it isn’t reciprocated. You constantly contort for him, trying to improve—also not reciprocated. You fight more. He leaves you. Your life ends again. You beg and plead for his love, and he ignores you. You posture and apologize, and he ignores you. You bare your soul to him for months, in an attempt to win him back. He ignores you. At this point, you have reached rock bottom. You feel a mixture of regret, fear, and grief—familiar feelings.

In 2015, you are still here. Suicide couldn’t kill you, twenty-two didn’t end you, and loss could not defeat you. You are living in New York City, where you’ve dreamed of living all of your life. It’s not as great as you thought, but you have improved immeasurably. You are angry and narrow-minded because of your newfound Black Nationalist ideals. You often feel lonely, but want to give the city and your dreams all you have. You go back to Baltimore every chance you get, and find solace in your solid friendships—you and Aniah are in a difficult place because he’s joined the military and is far away, but you’re still best friends. Everyone is proud of you, except you. You are still working on loving yourself and seeing yourself as worthy of love. You still have so much growing up to do, but you’re trying.

You spend a month in Hawaii; get eight of your photographs placed on billboards; get accepted into Parsons; complete your first photo series; and start working on a book of essays. You are more powerful than you’ve ever been. Your talent is growing and fostering your creativity. You are building a stronger relationship with your family, with a healthier perspective: You don’t blame or resent your mother—you love her now more than ever. You are learning to meet her where she is and deal with her alcoholism. She’s been clean from drugs for a few years, but still drinks her Steel Reserve. Although you still deal with depression, you are working hard to be kinder to yourself. You are still desperate to feel love, but you are more focused on reaching your dreams.

I know you are battling with yourself a lot these days, but I want you to take a moment to breathe in your accomplishments. You have lost so much, but you have gained so much more. Although you are not religious, you feel the grace, support, and spirit of Kirby, Aaliyah, and Duane. You know that they are with you, they forgive you, and they love you.