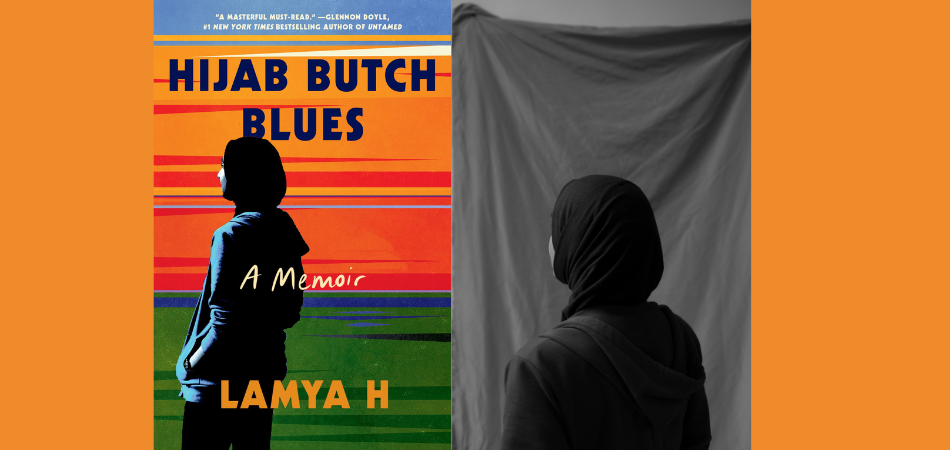

Taking its cue from Leslie Feinberg’s historic 1993 novel Stone Butch Blues, Lamya H’s debut memoir Hijab Butch Blues orients the emotional and political development of a genderqueer youth as they leave their South Asian birthplace with their family to go live in a rich Arab gulf country and then, much later, relocate to the United States to pursue an education.

The story structure resists simple categorization and this is one of the book’s most vital strengths. Here we find an author diffusing the simple chronology of life events that often keeps the format of the memoir confined to simplicity and linearity. Instead, Lamya embarks on a much more ambitious project. They name the different chapters of the book after surahs of the Quran, a tradition of queer scriptural adaptation popularized by Jeanette Winterson in Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit, and, employing their intimate knowledge of the Muslim holy book, they reckon with key figures in Islamic scripture by reassessing their allegorical interpretation.

In the Quran, Maryam, the mother of Isa, the prophet known in the Bible as Jesus, expresses her pain and remorse over her laborious pregnancy by the trunk of a palm tree, “She said, ‘Oh I wish I had died before this and was in oblivion, forgotten” (19:23). This is not a commonly cited verse. In fact, it is an extraordinary feat that Lamya is able to draw on textual minutiae and close read it for their own purposes. They feel a particular affinity to Maryam because they, too, want to die, “to disappear…to stop being alive,” and harbor no sexual interest in men. They’ve studied the Quran extensively and they know each of the surahs intimately. They are unconcerned with the authenticity of being “Muslim enough” that undergirds much diaspora literature and, for this and many other clever interventions, the book is a welcome relief.

Their assimilation into American culture is rife with challenges. They face homophobia among the Muslims in their study group and Islamophobia among the queers they meet at house parties, and it is their political integrity and intrepid moral compass that anchors all of these experiences. In wrestling with the meaning of the different surahs, they also uncover their own barriers to vulnerability. During the chapter named after Yusef, a Quranic figure who was left for dead at the bottom of a well by his jealous brothers, only to later command a ministerial position in the government where he comes to hold power over the fate of his brothers, Lamya debates the interpretation with her friend Manal, “I’m just saying that staying open to love is not some magic bullet that makes abandonment issues disappear, okay?” Yet it is not really Yusef they are debating. Both Lamya and the reader, though perhaps not Manal, are aware that the meaning of the surah pertains more pressingly to a woman named Liv, Lamya’s girlfriend of two years, who only wants them to “let your guard down” and “let me in.”

These are the moments of intertextuality that make Hijab Butch Blues a truly remarkable rupture in the literary fold. The teachings of the Quran here function to unravel their identity. Lamya shirks the expectation that they might embrace their queerness by way of abandoning their religion. Instead, it is through deep study of the Quran and engagement with the queer Muslim community in New York City that they finally discover a sense of spiritual belonging.

Like Feinberg’s book, there are sobering moments that point to the complexities and limitations of an intersectional queer community, as well as its joys and possibilities. In the Quran, Hajar is an enslaved Black woman who has a child named Ismail with her captor, Ibrahim. Lamya articulately questions the ethics of such an arrangement, “She is part of this, too, this woman, this Black woman, enslaved. But hers is the story that doesn’t get told.” With an unsparing eye for detail and injustice, they are invested in recuperating neglected or misrepresented figures like Hajar, and do not shy away from naming scriptural inconsistencies where they appear.

The final chapter resonated with me the most. Named after Yunus, also known as Jonah, the story is a famous one, of a man rejected by his community for his religious convictions and swallowed at sea by a whale, which is canonically understood as a consequence of having given up. Yet Lamya questions this exegesis. They see a similarity between their own life and the allegory of Yunus. Both have worn themselves thin fighting for the causes they hold dear and, in the end, both are left to decide how much longer they can struggle in vain to change the minds of others. It is both humbling and inspiring to read Lamya reassess even the language of giving up, “And I promised myself that if the conversation wasn’t constructive, I would—like Yunus, I realize for the first time—allow myself, and them, the dignity of leaving.” This principle invariably speaks to Lamya’s decision to abbreviate their surname and provide only contextual clues about the exact country of their birth and their migration as a child. Even in the form of the memoir, which by nature traffics in vulnerability, they refuse to surrender their totality.

The surahs of the Quran enable Lamya to sharpen their sword as an advocate for social justice. With a precision of prose that is at once riveting and clear-sighted, the ethical and spiritual lessons of the holy book are shown to empower their queerness instead of obfuscating it.

Hijab Butch Blues was published on February 7, 2023 by The Dial Press.