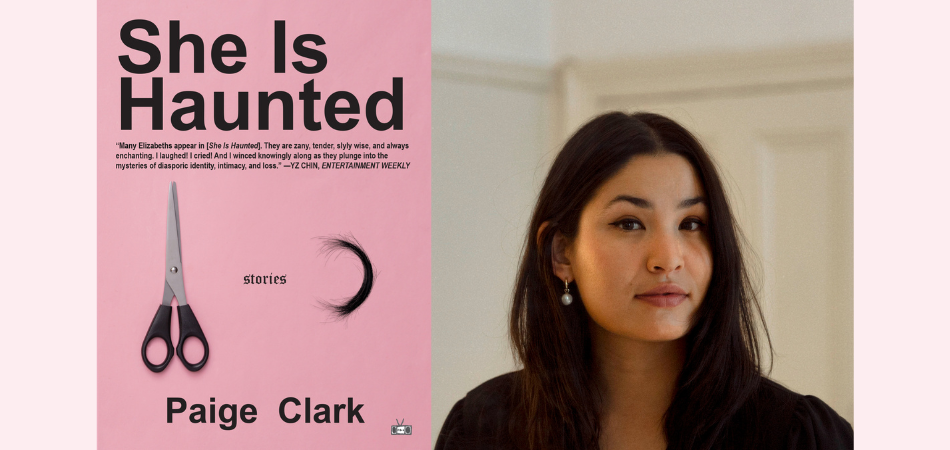

Paige Clark’s debut collection of linked stories, She Is Haunted, explores the shifting boundaries of selfhood amid loss and grief. Clark, a Chinese/American/Australian writer and scholar, harrowingly evokes our current moment: climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the rise in anti-Asian violence across North America all inform these stories. Many of Clark’s protagonists are mixed-race Asian women who grapple with how their heritage shapes their relationships with friends, family members, and lovers. More than a few of them are named Elisabeth (or variations thereof) and share overlapping histories and similar lexicons—as if they were parts of a single consciousness refracted across time and space. Clark’s prose is spare and precise, and she has a penchant for incisive satire that extends into speculative or surreal realms: in one story, characters have their brains surgically altered to better endure the rapidly warming earth; in another, the narrator works at a government call center for people who have recently experienced a breakup.

She Is Haunted was first published in Australia last year by Allen & Unwin. A North American edition was published by Two Dollar Radio this May. I spoke with Clark via Zoom about how her stories navigate complex questions of race and gender, and what it was like to edit and order the book.

—Michael Prior, Author of Burning Province

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Michael Prior: I wanted to start by asking about the stark, almost allegorical first story in She Is Haunted,“Elisabeth Kübler-Ross,” which explores one of the collection’s major concerns: the ways we confront grief and loss, and how such confrontations change us. The Kübler-Ross model of grief popularized the idea that one’s experience of grief progresses through five stages, beginning with denial and ending with acceptance. In the story, however, your protagonist struggles to accept the possibility of certain future losses and instead makes a series of deals with a figure referred to as “God” to preserve her marriage and her pregnancy; in the process, she ends up sacrificing her dog, her cat, and even her mother. Each deal she makes haunts her, recalling the book’s title. What inspired this story and what guided you toward its ultimate form? Why did you decide to place it first in the book? And how did you settle on the title She Is Hauntedfor the collection?

Paige Clark: Great questions. I have no idea how I did it! I think, as a writer, there are certain stories that I can come back to and remember what I did, and think, oh, I can do it again, but with that story, it was one of those very few times that a story just came to me. It’s the only story that has evolved out of my journals. I read this handbook about creative writing, and it said, “You’re not a writer if you don’t write every day.” So, I started this practice of writing every day; at that moment, I was at a crossroads with my partner at the time. We weren’t sure if we were going to continue the relationship or not, so that kind of bargaining, I think, was natural. There’s that impulse in the story of Oh, God, I’ll do anything to keep this relationship going—I even used the word God then, without meaning to. So, there’s something about that story that has all of that weight. But the voice of God and the woman speaking to God: that just kind of came to me during the writing. I wish I knew how I did it. It’s one of those things never to be repeated again, unfortunately.

As for the title of the story: It was originally called “Rumpelstiltskin” because I thought that it was a retelling. But after workshopping it, everyone said, Great story, but it’s nothing like “Rumpelstiltskin!”I really liked that title, and I was really set on it. But after everyone said it’s terrible, I went ahead and thought, Oh, well, this is about bargaining; I’ll just call it“Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.” Then, as the collection came together, that became its name. The name “Elisabeth” also became a theme in the book that ended up tying everything together—one of those beautiful things that you can’t plan.

And in terms of the collection, again, I had a different title for it, which was Of No Language, and my agent in Australia said “That’s a terrible title. That’s not going to draw people in: it sounds really stuffy.” As soon as she said that, I couldn’t unhear those critiques. And so she said, “Let’s just send it out as She is Haunted; we can change it later.” I really didn’t think it was the title, but my agent has really good instincts, and I trust her so much. So, we went with it, and then I couldn’t think of anything better. I kept thinking, I don’t wantShe Is Hauntedto be the titleand still workshopped other things. But in the end that was just what the book was meant to be called.

MP: It’s a great title! People and places in She Is Hauntedare haunted by the forces of history, the politics of their origins. In many of these stories, a relationship—romantic or familial—is haunted by events or other people from the past: I’m thinking of “In a Room of Chinese Women,” where an old flame of the narrator’s husband comes to visit, or “Why My Hair is Long,” in which the protagonist reflects on her difficult relationship with her estranged mother, observing that her mother’s absence is “like a phantom limb, the body’s memory of what is lost.” Then, there’s the Buddhist concept of “hungry ghosts” in the book’s title story (“The ghosts are preoccupied. They all have their own ghosts,” the deceased narrator wryly observes). How are you configuring the idea of haunting throughout these stories? Was this something that the collection was concerned with from the start?

PC: I think that’s eventually why I was okay with the title—because of these ghosts that follow the characters around. I was mostly afraid of the marketing side of that, and that people would think it was a spooky book: I was like, It cannot have a cover that makes it look like a spooky book!

I had a therapist who told me that I was dragging a bag of rocks around behind me. I lived my life just carrying a bag of rocks. So, I really thought of each of those ghosts as a rock, and, I think, in writing this story, I was leaving those rocks behind. But a lot of my characters can’t do that; I just see them all dragging their bag of rocks. So, a lot of the ghosts are very embodied in the stories, and I think there’s a real kind of physicality to them, and I really see them as being very present in that way.

MP: Speaking of embodiment, one of the things I really admired about these stories is the care and insight with which they explore race, gender, and embodied experience. Most of the protagonists are mixed-race women with Chinese heritage. Being biracial and of Japanese heritage myself, I’ve searched for fictional characters who reflect my experience, but I haven’t encountered many, and when I do find them, they often fall into reductive stereotypes. So, I admired the way these stories subtly depict their protagonist’s sense of their own identity—the various layers of who they are that, at certain moments, are thrown into sharper relief. How much of this was in your mind as you were writing?

PC: That’s such a big question. I’m still trying to unpack that for myself: how does one write one’s own identity? I think that, as you mentioned, it’s tough when you don’t feel like you have any models. I’m a real copycat writer. I look really closely at my heroes’ work, and that’s how I learn to write. And so many of the writers I admire are white writers, because that’s just what is being published. It becomes really difficult: how do I enter into that space? And for a long time in my writing I just didn’t do it—I guess this is my own narrative of being mixed and being really comfortable in white spaces. I think that’s maybe also why I don’t always feel the need to foreground race. I can slip into that state of being in my own whiteness, and that’s a real privilege that I had as well. But it got to a point where I couldn’t be a mimic anymore, and I needed to figure out what it was I wanted to say on the page—and maybe this goes back to this idea of the rocks, and how so much of who I am is in my body, and how people see me.

And then, there are the experiences that I’ve had which really are one mostly of a white American, because that was how my parents wanted to raise me: a very traditional, all-American kid. So, there’s this real duality and conflict in how the world saw me, and how I saw myself. At the same time, there’s also a longing to connect with my Chinese identity, and a longing to be a part of this great cultural history that my family has. I think all of those things came into the work.

Claudia Rankine talks a lot about writing into whiteness, so oftentimes writing the whiteness into my characters was a start. If I could show the ways that my characters were white on the page, I became more comfortable doing it. With myself as well. Oftentimes, I’ll make a point of making it obvious that certain characters are white to leave that space for the characters who aren’t, and not feel like I have to racialize the mixed-race or the East Asian characters in my story, because I’ve racialized the white characters. I’m still working through all of these things, and I also think that I have an obligation to write race outside of my lens which I haven’t been able to do yet, outside of highlighting whiteness. So, I’ll keep working at it.

MP: That’s a wonderful answer to a difficult question. I’m thinking about some of the stories in She Is Hauntedwhere the characters’ racial and ethnic identities are inextricable from pivotal moments in the plot. For example, in the final scene of “In a Room of Chinese Women,” both the protagonist and her husband’s former lover share a moment of worried solidarity while dining in New York’s Chinatown; I was struck by how the story alludes to the marked rise, or perhaps merely renewed visibility, of anti-Asian violence during the pandemic (“‘Do you get scared sometimes?’ she asked me”; pg. 82). I’m also thinking of how the mixed-race protagonist of “Lie-In” takes Chinese lessons out of a complicated sense of competition with another Asian woman whom she sees as a rival for her husband’s affection.

I noticed in your biography that you’re completing a PhD focused on the intersections of race, craft, and writing pedagogy. Has your scholarly work shaped this book, or perhaps changed your thinking about some of the stories here over time? How has your relationship with the book changed since its publication?

PC: My research started with my Master’s thesis, which looked at exemplification in popular Australian creative writing textbooks, and what writers they were using as examples. I did a count just to see how many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other writers of color were included in these books that were commonly being used—and still are used—at universities and sold in bookshops in Australia, and found that there are not very many, which was an answer that I was expecting. So, my PhD thesis looks toward what a more inclusive creative writing textbook would be, what that resource would be like and how it would help writers of color.

One thing that I had to get comfortable with—because I’m a bit of a perfectionist—is having things being out there that aren’t exactly perfect. In the edits of a book, there’s that final moment where it goes to print, and then you get it back. Those things you want to change—the discomfort that there’s an object out there that I will never be 100% happy with. That’s something I’ve just come to terms with.

In some of my earlier stories, I didn’t necessarily racialize the characters; I felt uncomfortable writing my own race. But I still feel like those stories are part of my journey and I’m okay with the fact that eight years ago, when I write wrote the first story that’s in the collection, I wasn’t comfortable with that part of myself: I didn’t know how to write about race. The stories that come next—I hope that they do a better job, or I hope that they gesture to something wider than what I’ve been able to do so far. But I’m okay with the fact that what I’ve already done doesn’t do that yet.

MP: What were some of the hardest and most joyful parts of editing this book?

PC: I love editing. I’m a huge editor. I think that’s where the writing really comes together. Sometimes I edit as I write, but I think that that’s a bit of a cop-out. Even if you edit as you write, you need to go back and edit and edit again. So, I think that the real joy of it was whittling it down and seeing the work become what I felt like it really should be, especially with some of the messier stories that hadn’t gotten as much editorial attention from me. The hardest parts were just the hours I spent thinking, Should this be a dash? Should this be a comma?while I looked at one sentence, feeling as though this decision was going to make or break the book. But that’s part of the writing process, and I know I’ll do that again when I’m sitting at the desk.

MP: I understand that completely; as someone who writes poems, I spend an inordinate amount of time debating between dashes and commas!

I often describe writing—or at least honest, attentive writing—as a process of discovery to my students. I was wondering what you discovered about yourself or about the book during the writing process?

PC: Yeah, that’s a good question. I get asked this all the time, and I never know what to say! It’s funny, because before I had ever been through the editorial process for a book, I heard other writers say, I learned so much about writing from being edited.And then when my book was finished, the only reaction I had was that I’ve learned so much about my writing from being edited. But I think the big thing that I learned—and this is something that Matthew Salesses talks about in Craft in the Real Worldas well—is that editing is so different from the workshopping process. Editing is a question: Was this intentional? And that’s really what the editor is going through and doing: asking, “Is this intentional? Is this intentional? Is this intentional?” That question really changed me as a writer, because now I can do that for myself. In my teaching, that really helped me to be able to ask that question of my students, instead of imposing my own standards or ideas about writing on them. I think I was approaching student work as a writer, which is actually not good for anyone. To be able to see how an editor would do it for me and then to put on the editing hat myself and be like, I can do that for you—that’s wonderful.

MP: She Is Hauntedcontains stories set in California as well as stories set in Melbourne. How does this transnational movement across the collection work for you? How have the different places you’ve lived and worked shaped you as a writer? And thinking back to our earlier discussion about race, how has having lived in both America and Australia shaped your awareness of race and ethnicity? Has that movement between countries allowed you to see the discursiveness of race, its material effects, in different ways?

PC: For me, moving to Australia, I was seen as an immigrant, but also as an other—not because I was an American immigrant, but because I have this Chinese face. Immediately, everyone thought that I was from Singapore or Malaysia, because Australia has a lot of immigration from those countries. I felt like I really had to unpack my identity in a new way. I grew up in Southern California, which is incredibly East Asian, and was in a comfortable space for much of my life. So, I think being thrown into these situations, where I got a new lease on my identity helped me to write that into the book.

MP: I love the humor in this book. The stories are often heartbreaking, but many of them contain these startling comic moments. In “Cracks,” the narrator describes her best friend as “a nitwit with a small head like a rabbit.” And in several of the other stories, sharp satire develops out of the stretching of a particular conceit to fantastic lengths, like a government department that advises people after they’ve been broken up with (“Gwendolyn Wakes”), or what it would mean to alter someone’s brain to help them better survive climate change (“Amygdala”). In the collection’s titular story, a woman experiences a Dantean journey into the afterlife, but her spiritual guide isn’t Beatrice or Virgil, but rather, Neil Armstrong. How did you come up with some of these more speculative conceits? And how do you know how far to push the satire?

PC: I don’t know if I know—I think I always push it too far, and that’s where editing is great: for example, maybe if I use this joke one less time, it’s going to land better. I think I’m guilty of that in my personal life as well: I hit on something funny, and I just say it one too many times—I’m that person—until the joke’s dead. I think I do that in my writing and I’m grateful for all my first readers and editors who pull me back.

Even if I know how a story should be plotted out, the magic of writing is when the jokes or the fantastic things just come to you. So often I start out with a last line, or a first line, or a structure of a story—I do it all different ways. I kind of know where I’m heading, but the beauty is where the play is, and maybe that’s something you can’t plan. I think that if you were to sit down and be like, I know! I’ve got a great story: Neil Armstrong’s in heaven—it sounds terrible, and it would never work. That’s the stuff, the magic that comes through in the writing. I always want to play on the page; that’s where I’m having fun. I find writing to be so painful and I hate doing it. I hate sitting down at my desk, and I’m okay with admitting that. But when I find the fun things, that’s what keeps me going and helps me get out the other stuff that I need to get down.

MP: Is that sense of play what drew you to writing in the first place? When did you start writing?

PC: I don’t think so. Not being able to go into that place of play is why it took me so long to find writing. I took a creative writing class in undergrad, and I got so scared I left after the second week. I just thought, I can’t do this, I can’t do this. Even then I wanted to do it well so badly that I was just absolutely petrified. I couldn’t even imagine playing on the page then. It took me years to get back to it. I worked in hospitality for about ten years, and for about five of those years I wasn’t even writing. But at some point, I just had this feeling that I was a writer. I kept telling people, “You know, I think I’m a writer,” and they said, “But you don’t write anything.” It got to the point where I couldn’t keep saying that without writing something, so I took an online course, and I finished my first story, which is the last story in She Is Haunted, and went from there.

MP: Earlier, you mentioned that the original title for the collection was Of No Language. That’s fascinating because in my annotations, I noted that the collection seems interested in exploring various languages, as well as thinking about different forms of language beyond literal utterance. Of course, the characters speak English and sometimes Chinese, but the book also casts other processes and forms of connection as language. In the story “Conversations with My Brother About Trees,” the protagonist meditates on how the language of biology might be the only language which holds both her and her mother in the same way. And food seems like another sort of language in many of the collection’s stories: it serves as a vessel for culture, a mode of communion, and a means by which to excavate the past. In a few of these stories, food is something that seems to bridge public and private selves, especially, perhaps, in the context of interracial relationships. Language-as-metaphor is a recurrent idea throughout the collection.

PC: When I sit down to write a story, I often think of it as a letter to someone. Usually when I’m inspired to write, it’s because I have something that I’m trying to say that I can’t figure out how to articulate in words—which is ironic, because words are my medium—but that is where that idea of “no language” came from. That there’s no language I could access that could convey what I was trying to say or ask of someone. I think that what you pick up on in “Conversations with My Brother about Trees” is exactly that: the mother character is of no language the daughter character knows—she often can’t be communicated within these stories. I am trying to reach out to someone or to capture a feeling that I can’t quite put my finger on; even in talking about it now, I can’t find the words. Maybe the ways that language fails us is something the book constantly returns to.

MP: This is sort of a sharp turn, but I wanted to ask about the way animals are incorporated into many of the stories: animals don’t share a spoken language with us, but we do communicate and connect with them in other ways. Joy Williams has this wonderful quote about how every story needs an animal within to give its blessing, and most of the stories here include animals, many of whom seem to assume figurative import. There are several chihuahuas; there’s a squirrel named Ron; there are quokkas; there’s a rat that falls out of a tree; a couple hamsters, who are, sadly hurled from a tree; even an echidna trying to cross a highway. Animal blessings abound! I was thinking about how these inhuman creatures emblematize not only otherness, but also the possibility of connection across that otherness—the estrangement we feel from ourselves and others at times, especially between cultural and ethnic backgrounds.

PC: That’s a great reading of it. The animals might go back to this idea of play, in that they bring me joy, even though some of the stories are quite dark. Especially with dogs; dogs bring me so much joy. I couldn’t help but bring them into the stories, because so much of my life is my relationship with my dogs over time—they’re really essential relationships in my life, and so I felt that had to be in the book, or that I just represented it in other animals without even meaning to.

I think “Conversations with My Brother About Trees” also touches on how my way of being anti-racist or engaged in social justice is through ideas of environment, through this idea that every single living thing—be it leaf, be it rat falling from the tree—all have inherent value and equal worth. Thinking about this in a philosophical way—about the value of everything—humans are definitely not more important in any way than these beautiful trees.

MP: That certainly speaks to the ecocritical stance the collection takes at many points, and the way it thoughtfully incorporates the current moment, be it climate change or the pandemic.

I was wondering which books were important to you while writing your book. While reading She Is Haunted, I heard echoes of Amy Hempel and Aimee Bender (later I came across an interview where you mention both those writers)! And there’s a line in one of the stories that riffs on Margaret Atwood’s re-writing of the Odysseyfrom Penelope’s perspective, The Penelopiad.

PC: There’s also a writer called Ellen van Neerven, and their work was important in terms of thinking about the collection as a whole. They have a book called Heat and Light, and it’s so exceptional, what they do in terms of expansiveness. I think that collection was probably the best inspiration for me because it contained both real and surreal worlds in the same way that my book does. I also reread Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, which, of course, is such a classic. I really am drawn to that singular narrative voice; it really does feel like it’s almost one continuous narrative, even though it’s short stories—that was another model for me as well.

MP: I hadn’t heard of Ellen van Neerven—I’ll be sure to read Heat and Light. Speaking of Australian writers, one of the things that seems a shame is just how little English language writing from the rest of the world crosses into the States. Who are some of the English-language Australian writers we should go check out?

PC: Well, there are so many, but definitely Ellen van Neerven, who I’ve just named. I also love the semi-autobiographical novel, Snake, by Kate Jennings, who recently passed away—her book is exactly the kind of writing that I want to do. Snakeis set in rural Australia, and I think Jennings does an incredible job of writing her own whiteness. It looks at the whiteness of being in a rural Australian landscape in the eye, which I think is bold. And her language is so great and full of play.

I also love Dorothy Porter. Do you know Dorothy Porter? She wrote a verse novel called The Monkey’s Mask, which is absolutely brilliant. And again, it does two of those things I love: it has such consideration for language, while also being full of play. It’s a fun kind of whodunnit or murder mystery, but in verse! And spanning genres, I also think The Drover’s Wife—which is a play by the Aboriginal author Leah Purcell—is exceptional.

MP: I’m looking forward to seeking out these books. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me, Paige!

PC: Your questions made me think about my own work in a new way. That’s the great part about publication: having a conversation about your work, and then being able to bring that to what you’re working on next!

Paige Clark is a Chinese/American/Australian fiction writer, researcher and teacher from Los Angeles. Her first book She Is Haunted (Two Dollar Radio) was shortlisted for the Readings Prize and longlisted for the Stella Prize. In 2019, she was runner-up for the Peter Carey Short Story Award and shortlisted for the David Harold Tribe Fiction Award. She has a Bachelor of Science in Mass Communication Theory from Boston University and a Master of Creative Writing, Editing and Publishing from the University of Melbourne, where she is currently at work on her PhD. Her research addresses the relationship between race, craft and the teaching of creative writing.

Michael Prior’s second book of poems, Burning Province (McClelland & Stewart/Penguin Random House), won the Canada-Japan Literary Prize and the B.C. and Yukon Book Prizes’ Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. He is the recent recipient of fellowships from the Jerome Foundation and the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Writers and Scholars. His poems have appeared in Poetry, The New Republic, Kenyon Review, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day series, among other publications.