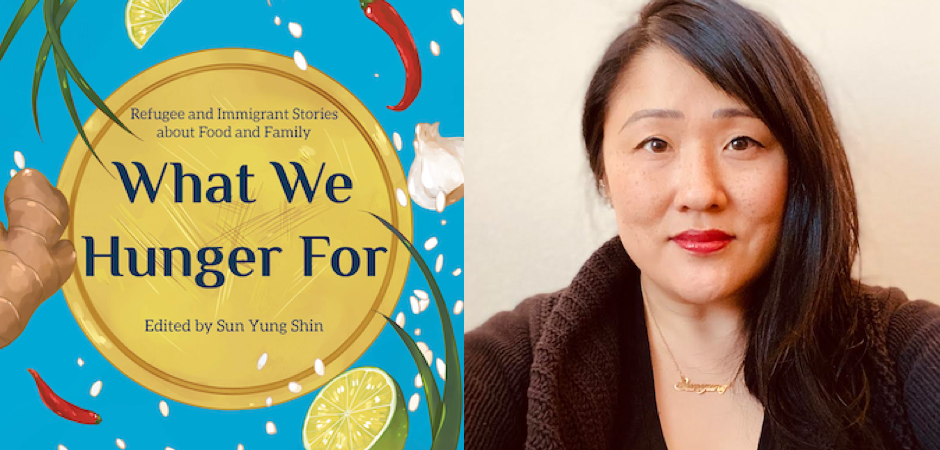

A Conversation with 신 선 영 Sun Yung Shin

In What We Hunger For: Refugee and Immigrant Stories about Food and Family, writers speak about all the contexts, ancestry, racism, and communities linked to their most cherished dishes. Editor 신 선 영 Sun Yung Shin brings us this collection of essays from writers of color living on the homeland of the Dakota people, also known as Minnesota, to showcase voices often minimized in prevalent conversations about what, how, where, and why we eat.

Food is active in these pages — it heals, identifies, connects, and resists. From conjuring up homelands and childhoods to validating ancestral lineage to sustaining communities during COVID, the writers probe the ingredients they associate most with themselves. These pages offer recipes, an acknowledgement of colonialism and white supremacy’s imprint on our plates, and a beacon of truth for those whose foods might have been a source of estrangement and shame in a white supremacist society.

신 선 영 Sun Yung Shin and I communicated via email in June 2021, as the pandemic waned, restaurants reopened, and people began to enjoy more communal food experiences.

—Victoria Cho, Contributing Editor

Victoria Cho: Reading this text, I had so many memories of my mother cooking, the occasions surrounding some of her dishes, and our freezer stocked with frozen fish and bones. What is a food memory you have from your childhood?

Sun Yung Shin: I remember watching the strawberries in my mother’s garden grow over the course of a few weeks, from small white flowers to little white beads with specks on their surface to bright red berries dimpled on the outside. This feels like one of many formative experiences that taught me how completely magical life on our planet is, and how so many delicious foods grow right out of the ground, ready to eat. I grew up as a Korean adoptee in a white family, which I discuss a little bit in the Introduction, and my adoptive mom told me about how her grandparents, who lived in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, moved to Menominee, Wisconsin at some point to try to be farmers. They bought some land that was “full of rocks.” They failed and had to move back to Chicago. My maternal grandmother, their daughter, grew up in Chicago during the Great Depression and had to leave school in sixth grade (and never go back) to work at a deli to support the family. My mom is also the one who taught me to cook and bake; she was a much better cook than her mother, may she rest in peace.

VC: The title, What We Hunger For, recalls a sense of longing, maybe even desperation. The book offers insights about ancestry, colonialism, recipes, trauma, and economy — an amalgamation of elements, such as those that might comprise a dish. When editing this piece, were you hoping to highlight certain notes that might complement each other, like one might do when putting a dish together?

SYS: What a lovely question, thank you. I was definitely hoping in the original call for submissions that we would make more visible to each other and to readers the threads that bind us together as migrants, and ultimately just as human beings, who ended up here in the United States as living beings interdependent on one another. The magic of cooking, of transformation that cannot be undone (once you make a cake you cannot reverse the process to end up with the separate ingredients in the same state), has so much to offer us, I think. I think of metamorphosis, and of a word that is sometimes weaponized against marginalized groups: resilience.

VC: I want to acknowledge your healing practice and hear more of your thoughts on food as medicine. I laughed and cringed with recognition when I read from Kou B. Thao’s essay about the white doctor’s instruction that Thao’s Hmong friend stop eating rice (“How the hell am I supposed to stop eating rice?!”). I’d love to hear more about how your healing practice might incorporate food. As Junauda Petrus-Nasah says in the final essay, “Lake Superior Looks Like the Ocean to Island Girls from Minnesota,” “food is truly medicine.” Do you have any specific healing philosophy related to foods from one’s ancestry?

SYS: Yes, I think so many people can relate to that! I consider myself an emerging healing practitioner. Also, so many people do healing work, whether or not they consider themselves healers or are recognized in their communities as healing others. Food is definitely medicine, or can be! And I want to continue to deepen my holistic understanding of that.

My somatic healing practice is hands-on; biodynamic craniosacral therapy and also Reiki. It is about the nervous system and all somatic systems, as well as qi or chi (energy). I feel like I am just beginning to learn about how to think about food and what some people call “vibration,” or eating for “high vibration.” I suppose that eating something that has had a life of pain and suffering at the hands of humans would be eating “low vibrations.” I know that sounds woo-woo, but I think we just don’t have great language in English for what so many of our civilizations have known for thousands of years. How to live in biological and spiritual balance, how to not take too much, how to give back, how to learn from plants. As my Native friends and teachers, such as Diane Wilson, Dakota, say, “plants are our teachers.” And as Robin Wall Kimmerer and others say, “we need to heal our relationship to the land.” I believe this at a deep level and want to continue to work to align my day-to-day life with this ethos, this way of being.

VC: With the onset of summer, I think about global warming and the catastrophic fires of the West Coast, along with other ways our land is deteriorating. I was reminded of the land, the stuff of which we’re made, when reading the writers’ Indigenous land acknowledgements and descriptions of terrain on which crops are cultivated. Have you always had a reverence for the land? Has your relationship with land, however you define it, changed over time?

SYS: I haven’t! I wish I did! No one I knew was talking about the environment or climate when I was growing up in the late 70s and 80s and early 90s. The American culture was more concerned with being bombed by the U.S.S.R. So my relationship with land has definitely changed over time. A big shift happened when I went back to Korea in 1987 and saw the beauty of Korea — the rice fields, the mountains, the greenness. I definitely felt a sense of belonging to all that in some primal way, although I couldn’t articulate it at the time. But it has deepened since then; I made my fifth trip there in 2018 with my two kids. Another big shift happened when I took a solo road trip to the American West Coast and traveled through so many different types of lands and climates. It gave me a much more visceral and spatial sense of the biodiversity and geological diversity of this continent and also the scope of the colonial project, and the violence of manifest destiny.

VC: Often food conversations in the U.S. neglect the Midwest and focus on celebrity chefs or cities on the coasts. What do you think might be the prevalent perception of food from Minnesota, and do you think that perception is shifting at all?

SYS: I really have no idea! I know that there are James Beard winners here that I would hope have the respect of coastal elites in the food world, but I really don’t know. I would hope that the perception would shift toward the positive, because there are a lot of exciting food-related developments here.

VC: Valérie Déus writes in “Haitian Kitchen” that “Food is resistance, and I just refuse to let the things I love about myself disappear for the sake of blending in.” I think of the ways in which I felt self-conscious about what I ate as a child, never seeing foods from my household in a neighboring household at that time and wondering how my friends might respond. Are there ways that you have consciously chosen what you cook and eat to assert your specific identity, rather than join a prevalent trend?

SYS: Yes, definitely — right now I live in an all-Korean household and we eat Korean food frequently, if not daily, and that has been so healing for me as an adoptee who has never lived with other Koreans — since I left Korea at age 1.5 — who weren’t my own children! Over my time in Minnesota, I have had wonderful Korean American friends who are very good cooks, and we eat Korean a lot. I have always eaten it at my own home, but I haven’t lived with anyone who has made it for me, and that has been so profound and wonderful. I’m very interested in Korean cuisine and hope to explore it through writing (and more cooking, growing) more at some point.

VC: I’m curious about the mutual aid movement in Minnesota, especially during COVID and Black Lives Matters activism. Simi Kang delves more deeply into mutual aid and the Sikh community’s alignment with this organizing principle in “Taking Langar.” Have you seen mutual aid movements in your area?

SYS: Yes! So many! Minneapolis has a lot of mutual aid efforts and ongoing practices, which have helped people survive and live. I’ve experienced Minneapolis (I won’t speak to St. Paul since I don’t live there, and the cities can feel quite separate and different) as being a place of mobilization and strong community the whole time I’ve lived here since after college. There’s been so much going on I don’t even know where to start — we could talk about the unhoused encampments, queer community mutual aid especially around housing, disability justice work around surviving the medical industrial complex, and the healing justice community. A recent concrete example is that I was able to participate in a community healing day at the Daunte Wright memorial site, organized by local artists and organizers Shá Cage and e.g. bailey and several others. Another craniosacral therapist and I hung out on the boulevard, along with people from The Million Artist Movement and many others, and offered support to anyone who wanted to sit in a chair and receive. Ananya Dance Theater dancers performed and there were a lot of people present, being there, being together. Grieving, connecting, hoping.

VC: I really appreciate Michael Torres’ insight in “An Unfortunate Mosaic” about food seeming like an access point for authenticity and for validating one’s identity. I’ve often felt this way about my connection to Korean culture — food might be the aspect of Korean culture I am most familiar with, and at times when I am feeling insecure about my Korean ethnicity, I will think about my relationship with Korean food. Do you have any experiences like this with food helping you access parts of yourself?

SYS: Definitely, especially since Korean culture is thousands of years old, and time is so important in, for example, fermentation, whether we’re talking about soy sauce or kimchi or 막걸리makgeolli (a low-proof cloudy rice wine), which has been brewed since the first century BCE.

VC: I want to highlight your jewelry practice, including your gorgeous line of earrings. I noticed your jewelry incorporates animals, such as snakes and cicadas, and natural elements like lightning bolts, suns, and honeycombs. Do you find your other artistic endeavors — jewelry, poetry — are as connected to the land as these essays?

SYS: Yes, I like to think so! Adornment is so universal, and as old as our species if not older. We need food to live, and our plants need soil and water and sunlight to grow, and we are all bound in an intimate, interdependent web. Well, other species don’t need us (except maybe our microbiomes) but we depend on other species for our survival. We should be honoring them if not worshiping them. We should humble ourselves before their age and continuity. The elephant shark has been here for 400 million years, the nautilus has been here for 500 million years, and the jellyfish has been here for perhaps 600 million years. The winner, cyanobacteria have been on the planet for perhaps 3.5 billion years. What are we (humans) even but a wisp of breath? Not even! Jewelry and poetry and tarot and other things I do are about reverence for the world, for the symbols that we use as portals to a more profound sense of connectedness to all things, including celestial activity. During this year’s planting season I read that the moon can dictate when it’s the best time to plant seeds because of its ability to draw water through the soil toward the surface. I’m not sure if that’s true, but it would make sense, considering the ocean tides. Even if it’s not true, that’s some poetry.

VC: What kinds of foods or healing practices have been helping you during the pandemic?

SYS: During the pandemic I was fortunate enough to work remotely and that gave me a lot more time to cook. So just slowing down and preparing food with more reverence and curiosity and patience has been healing. I hope to maintain and even strengthen some of that, some of the time, even though I am now attending more things in-person and will be teaching in-person, etc. I hope to continue to try to make Korean dishes that I haven’t made before, and enjoy harvesting my household’s vegetable garden, my apple tree, and doing some preserving this fall. Eating food that you have canned yourself, in the winter, is like opening bottled sunshine and time traveling. That’s pure magic.

신 선 영 Sun Yung Shin is the editor of the best-selling anthology A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota and author of the children’s book Cooper’s Lesson and three poetry collections, including Unbearable Splendor, winner of a Minnesota Book Award. She is also a biodynamic craniosacral therapist, cultural worker, and educator.

Victoria Cho is a Korean American writer who was born in Virginia. Her writing has appeared in SmokeLong Quarterly, The Collagist, Perigee, Quarter After Eight, Word Riot, and Mosaic. She is a Kundiman Fellow, a VONA/Voices alumna, and was Co-Fiction Editor of Apogee Journal. Victoria has received support from Vermont Studio Center and led creative writing workshops for New York Writers Coalition. She lives in New York City.