An Interview with Safia Jama

Safia Jama’s Notes on Resilience, the poet’s debut collection, mines the artifacts of childhood to ask questions about home. The collection expands simple ideas about grief, navigating not only the speaker’s grief over losing her father, but also the grief of missing her father when he travelled to his home country of Somalia for work; and the grief her father experienced when losing his own sister; the grief of separation from kin across the ocean. Notes on Resilience is part of the Akashic Books New Generation of African Poets chapbook box set. Order the box set here, and find a reading from the launch event here. Apogee Journal’s Executive Editor Alex Watson spoke to Safia over Zoom in late October of 2020. They discussed process, following objects and images, and respecting the pain of the poem.

—Alexandra Watson, Executive Editor, Apogee Journal

Alex Watson: The last time I saw you was right before lockdown began, at the beginning of March. You were the first person I heard say the phrase “social distancing”!

Safia Jama: I have thought of that moment, bumping into you on the airplane, sharing a taxi from the airport. I remember feeling like it was important that we connect, even in the in-between spaces. All of these memories feel so otherworldly now.

AW: How has writing been going during the pandemic?

SJ: I have been writing, but in a different way. Around the time of the quarantine, I instinctively started to keep a notebook. I have a notebook in front of me. I started this one in December, this pink composition book, which I bought when I finally had the courage to go to the drugstore. Everyone was kind of in shock, we had been told to stay at home, and my CUNY classes were suspended. I had this sort of weird free time. So I would take my little notebook out on a walk. I live in Brooklyn, pretty close to Prospect Park. It has been a real gift to be able to escape into the park. I took notes during my walks dedicatedly for a couple of weeks. The idea of recording things became important, not drawing from my imagination or memory but more so just writing down my day-to-day mundane existence. It became a kind of grounding practice for me. That’s been comforting.

And the practical writer in me wants to be able to look back at this time, and know how I spent my Monday in some July of 2020, because these things, we can forget so quickly. So it’s been more of a practice than a product at this point. That being said, I have created a few new poems. I have a little folder on my desktop: “Poems 2020.”

AW: I like how you talk about materials, or different modes of approaching materials, like memory, imagination, and recording. It sounds like when you look at the recording in the future, perhaps you’ll construct a moment in a more artistic way, when you’ve made more meaning out of these experiences.

SJ: Hmm, I like that idea of the memory kind of filling in the gaps, rushing in like water around the rocks.

AW: Well congratulations on your debut poetry collection Notes on Resilience! Can you talk a little bit about your vision and process in creating the chapbook, and how you upheld or deviated from that vision? Did anything about the final product surprise or satisfy you?

SJ: The editors, Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani, invited a group of African poets to submit to the boxset series. This is the seventh year of that series. I had submitted a full-length collection to the Sillerman First Book Prize. They saw my poems through that avenue, and I was invited to submit. It’s almost like a hero’s adventure, where I got the email last spring: this is Kwame Dawes, you have two weeks to submit a chapbook manuscript. I had to reinvent a mini manuscript for this chapbook, rather than try to submit a short version of my full length. So I went with a new title. And I didn’t think so much about a concept that all fit together. I thought more in terms of what’s my strongest work.

I think it’s important as artists, having a sense of our reader. I think that’s what sometimes makes it so hard to go through the submissions process, because you feel like you’re sending work out into a void, or into an unknown, but I think it’s a real gift when you know that a writer who you admire and respect will be reading your work. I think that experience causes you to grow and to see your work in a different way, in a way that is healthy and helpful.

Kwame Dawes was my editor, and he hand wrote edits on my manuscript that were then scanned and sent to me. Speaking of materials, that had a real tactile quality. There were some long notes, and some line edits, and I hadn’t really had that kind of feedback since being an MFA student. It was intense, but ultimately, I knew that Kwame had my best interests in mind. So I trusted his feedback, while also trusting my poems. I tried to keep those two things balanced and then we met in some intermediary place, so I saw it as a collaboration. And he brought a clarity to the vision. We cut a number of poems. I think that that lent the final work a clarity that was a surprise to me, because we all have those favorite two poems that we just always keep in the manuscript and it would never occur to us to cut those poems. But then, the other poems shine brighter without those favorite two poems of yours. They may be needed for another manuscript.

I have to shout out a friend and a poet I admire, Matthea Harvey, because I was pretty much on my own when I was putting together the manuscript–I hadn’t had time to ask anyone for help. There wasn’t a red button in my room that I could press, or a phone like in Batman. I happened to be meeting up with Matthea and I ran a few titles by her. And when I said “Notes on Resilience,” she’s like, “That one!” I think that little nudge helped. That was like a little secret boost that I got in the process. Like I said, hero’s journey–we always need that mentor to appear at the right moment.

AW: That’s fantastic. I was going to ask about how poems made the cut. Do you have a sense of the criteria by which poems were included or excluded?

SJ: I think the poems that knew who they were included. There are those poems that are maybe wearing a fancy dress but they’re not really sure. Kwame saw through that. And, and for those poems I’ll be looking at them and saying, oh I wonder who this poem really wants to be, whereas the ones that just were, they were doing their thing.

I think clarity is the quality that made the cut. It’s almost like a sculpture or something. And sometimes the sculpture just isn’t quite done, there needs to be more chippings away at the form, in order to really find out what’s inside the rock that wants to reveal itself. And some of them just were fully formed, you know. Sometimes a poem may know who it is and be its full self and some people won’t like it. That’s okay too. At a certain point, it’s about, knowing in your own heart or gut why it’s special to you and why you remain loyal to that poem, regardless of what anyone else says, and that’s something I’d like to make more room for and cultivate in myself. I kind of admire those poets who don’t really run their poems by anyone, that independence that some people have. I don’t know if I’ll ever be that poet, you know.

AW: I love that you describe clarity as such a central value in revision and also building the collection. This book is very accessible, not to say that it’s not complex and dynamic and doesn’t have references in it that I am not familiar with–there’s a lot to learn from it. But at the same time, I’m not getting caught up on what the line means. I’m curious about in your journey, from the MFA to being an editor, as well as a writer and a teacher. Whether that kind of value of clarity has emerged over time, whether it was something you always held up as a value or whether you might have been like me, assuming good poetry is kind of confusing or something that I don’t really have full access to.

SJ: It’s a great question. I have gone to the other extreme. I remember writing some poems when I was in Brenda Shaughnessy’s workshop at Rutgers-Newark. I had some poems that were pretty out there, you know, and she was open to that, experimenting. I think there’s value in that as well, to be obscure and difficult has its own pleasures. Like the way you might enjoy a certain food that is more difficult to appreciate, and some people taste it and think it’s disgusting, and other people will think it’s the most refined flavor they’ve ever experienced. You know what, I still remember one time I was in a sushi restaurant trying sea anemone. I couldn’t eat it. I had to spit it into a napkin. But to this day, I still think about it. I think maybe there’s some way I could have appreciated that. I respected it, it conquered me. I hope at some point that I will write and share poems that are impossible to understand.

But I do really treasure clarity, above all. I was inspired by the work of Lucille Clifton, which I was reading when I got back to writing poetry, when I was in my late 20s early 30s, and reading poems from her first collection, Good Times. All of her poems, they’re so clear. And there’s nowhere to hide, behind any phrase or sentence, they are laid bare. I do want my poems to be accessible to as many people as possible. Not just poets.

AW: I’m always stressing to my students that the clear sentence can hold the complex idea. In a way, the reader gets to grapple with the complexity of the ideas when they don’t have to worry so much about the complexity of the sentence or line.

SJ: Out of that clarity can emerge the most complex ideas. I think there’s a problem if we rely on vagueness and pretend that it’s complexity. I think vagueness is to be avoided if at all possible. I try not to be too critical, but sometimes it’s good to know what your values are as a writer and poet.

And there are political ramifications for clarity, versus vagueness. This being Apogee Journal, I think we can go there. I never really felt like I had the privilege of being vague, I could not lean back on that, because it is a privilege to be vague in your art. Because you don’t have to expose yourself, you don’t have to make yourself vulnerable. You can sort of hide, and no one will challenge you.

AW: I’m theorizing about what creates the feeling of clarity in this collection for me. I think that it’s about people and things. I mean, it’s not all concepts. It’s very grounded in people and also images and objects. I was struck by, in the first section, the way toys (the Fischer-Price toy castle in “Dad’s Last Visit,” the carousel of horses and flashlight in “Two Gifts,” the “menagerie of beasts” in “My Brother’s Menagerie,” even the “mother’s old polar bear collection” in “Lies”) become these artifacts for storytelling and memory. Can you talk a little bit about how you think about the relationship between images or objects and ideas? Do the images come to you first or the ideas?

SJ: The objects come first, the imagery comes first. I don’t set out with an idea of what truth will emerge in, say, writing about the carousel or the toy castle. These are real objects from my memory. I love that you call them artifacts, because it is a bit of an archeological dig, where you have this fragment, and it stays with you and you’re fascinated by it. It won’t leave you alone until you write about it.

I do have a fascination with these toys from my youth, and that’s important. There’s something about these toys. I’m not done with them; there are other toys I want to write about.

AW: It’s a good lesson for beginner poets, that the specificity of something material can often get at an idea in a more surprising or interesting way. It can sort of fall flat if you start with the idea, in some ways, because it’s giving you nothing to discover about the artifact.

SJ: Yes. And it is an act of play, writing a poem. Any creative act is fundamentally, for me, on a higher level, an act of play. Children don’t need a lot to sit down and play and feel engaged in life. During this pandemic I’ve been fascinated, walking around and watching children, and seeing what they’re doing. They don’t have enough to do, but I think the ones fortunate enough to be able to go outside and play, have gotten better at playing in a sense, because they have not had as much regimented activity. I see them climbing trees or digging in the dirt or playing make believe, and that’s been wonderful to watch.

But I think in the same way, when I sit down to write, it’s hard to let go of those ideas. Yeah, it’s hard to let go of one’s agenda. It’s hard to do as an adult. But I think that’s when the poetry really happens. I want to cultivate that more, where I really make the writing into a moment of invention.

AW: Childhood and play feel relevant to my reading of this book. It really mines the experience and feelings of a child, even while it’s a mature perspective, it explores childhood. I love the figure of the brother in these poems. I’m assuming he’s an older brother. As someone with an older brother, I related to the torment and petty struggles, especially in “Two Gifts.” “My Brother’s Menagerie” ruined me in the best way (“I keep a menagerie/of beasts my brother set free/ then set upon me.”) For me, the word “keep” feels so essential to that line–it takes the experience beyond the realm of the past and into the present and future. Can you talk about how the idea of “keeping” might inform your poems? Sort of like the recordings of your daily walks, but more constructed?

SJ: I was recently thinking about that line, and thinking about how that “keeping” claims a certain agency in the line. And it’s paradoxical, too. It may take time for the meanings to reveal themselves to me. I think that’s natural for a poem. Sometimes it may take years to really understand what your own poem has to teach you, or what someone else’s poem has to teach you. But the paradox of keeping the menagerie of beasts that have been released. And yet the cages are empty. And so, wait a second, you know what’s going on here, where am I keeping the menagerie of beasts, if the cages are empty now? Maybe it’s the poems that are the cages. The act of writing the poem is an act of containing those beasts, in a way. So there’s mystery in it for me too.

There’s also pain. There’s a lot of pain in these poems. There’s something about that word keep that strikes a note, even the sound of the word keep. You catch your breath. There’s a longing, but there’s also a note of pain.

AW: That last line is so powerful: “Animals may hurt each other in captivity / but a baby elephant left alone will surely die.” There’s the pain of the beasts, but there’s also the alternative of loneliness.

SJ: Yes. I remember first reading that poem at Cave Canem, when I was a graduate fellow in 2015. I read that poem the week I wrote it. And Tameka Cage Conley came up to me and said that was a tender poem, and she could see the love in that poem. It was not just about my pain but it was also about love. That’s important to me too, that my poems are concerned with love, in some shape or form. And that may be love for myself in some cases. But, also love for other people. It’s a hard line, “a baby elephant left alone will surely die.” But it’s also true.

AW: I feel that that pain and love coexisting through so many of these poems. And the one that’s coming to mind for me right now is “Two Sisters”. I think especially because we sort of have this separation and yearning and loss, especially around the father in other poems, and in this poem, we’re actually inhabiting his loss. It feels different from the other poems. Can you talk about that act of imaginative empathy, to reimagine the loss of the sisters?

SJ: It is different. It’s a different set of responsibilities when you’re writing about someone else’s experience and someone else’s pain. I had that poem archived for a long time. That’s one of the oldest poems in the collection. I remember thinking, I’m not going to send it out to any journals. Part of my process is reading a poem publicly. I enjoy that particular act of speaking the poem in front of people. There’s a performance element to that, too. I remember I read “Two Sisters” at the Bureau of General Services—Queer Division. I remember Omotara James was also reading, and she was sitting in front of me in the first row. I had read that poem before without too much emotion, but I remember there was a full moon in Scorpio that day. That day was supposed to be emotional.

I read it, and I wept. It hurt, but I’m glad, because I felt like I was respecting the poem and respecting how much pain was in that poem. After that I felt better about publishing it, and that’s partly what inspired me to include it in in the chapbook, and for that poem to be housed in the box set and to be part of this larger conversation. For my Somali aunties who inspired the poem. It felt like it was the right place for that poem.

I inherited that story, I didn’t invent it from my imagination. It was imparted to me. And so I just tried to do my best to present it in a proper way.

AW: I felt what you said about your Somali aunties inspiring this. There’s something about inhabiting someone else’s experiences of pain. Sometimes the thing that makes me cry is thinking about someone else’s pain. Like you’re channeling your own pain through someone else’s experience.

SJ: When I cried when I read “Two Sisters,” it wasn’t just empathy. I think I was also crying for myself. That poem gave me access to a part of myself that I wasn’t able to access before. Empathy can be a gift to the person who feels it. If you can feel for someone else, you can feel for yourself, too. It goes both ways. I always felt like I wanted to be able to feel that poem fully, to feel the loss fully, and to better understand my father’s loss.

I’ll interchange back and forth–sometimes I’ll say “my father,” sometimes I’ll say “the father,” or “I” and “the speaker”–I take license to switch back and forth. What I’m saying is, there’s a relationship between feeling one’s own pain and feeling the pain of others. I don’t think we can just do one or the other–I think they’re connected. I always knew that I would have to fully investigate my own pain in order to fully appreciate the pain of others. And that is fundamentally, you know, a useful and moral thing to do, as a person, you know, it’s not frivolous, it’s not self indulgent. It’s a very practical thing to devote time to feeling your own pain and understanding it, and then you will be able to have more space for other people’s pain.

AW: I hope readers of the chapbook will recognize not just the powerful explorations of grief and loss and resilience, but also the humor–that emotional range. I’m thinking of “The Victorian Era” which pokes fun at the British Empire (“It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities, and national self-confidence. And crumpets”) while also alluding to the more serious topic of how the empire partitioned Africa. I’m wondering whether you think actively about the role of joy, fun, or humor in your work, even when discussing serious topics.

SJ: Thank you for getting my humor. It’s refreshing to hear you talk about humor. It’s one of the crayons in my color box. It’s that stubborn insistence to not hold back different parts of my voice. Oftentimes we may feel like we have to have a particular style or a particular note. Or if you’re writing about painful subjects like colonialism or trauma, you’re not allowed to crack a smile, you’re not allowed to find humor. But I think we need that humor. That’s part of the resilience–that’s part of how we survive. Making room for that humor. I think it’s something I grew up with. My mother has a very dark sense of humor. Somalis also have a dark sense of humor. A writer that comes to mind when I think of that poem is Evelyn Waugh. He had a book Decline and Fall. He would write about these terrible British people doing terrible things in colonial outposts, and I remember always being surprised at the humor, but admiring that dry, British humor.

My father went to a British colonial boarding school in Somaliland. I sometimes think about that inheritance. That he was learning English, he had these pseudo-parental figures when he was sent away to school, these colonial Englishmen, and I wonder where that is in my makeup. So if I’m reading a novel by Evelyn Waugh, somehow that’s built into my cultural DNA, it speaks to me in some odd way.

AW: That’s fascinating. I’m interested in the fact that the poem mentions Ireland. Poems can make connections between empirical projects. You’re using sources, but you don’t have to make an argument for why the partition of Africa and Ireland’s population decreasing are connected. They’re just in the poem together so they speak to each other in some way. I guess that’s how I’m thinking about it, the way poetry can bring together what might seem like discrete contexts and topics. Is there anything about your process in working on a poem that uses sources that you’d want to share?

SJ: Well, that one was a big one because I did borrow phrases from a Wikipedia entry on the Victorian era.

I’d like to do more of that. Sometimes I feel like it’s cheating a little bit, but I’d like to allow myself to do more of that. Particularly with respect to history, because there’s so much rich material. And I think poets need to get at history, we need to rewrite it–queer it, or mess with it, to get at the truths that lie in the silences.

AW: Yeah, that makes me think of Layli Long Soldier’s poems in Whereas, the ways that she uses these legal documents and rewrites or undermines them in different ways. While saying “I’m not a historian,” but that’s not just a lack, not being a historian is not something that a poet lacks. It’s a benefit in some ways, because there’s something, a meta reflection on the way that language shapes these historical narratives, and just drawing attention to one’s own language is something that maybe destabilizes our sense of the historical record.

SJ: I’m thinking about that question you asked me earlier in our conversation about, to what extent an idea comes before the image, versus the image coming first and then out of that springs the idea. With the Victorian era, that may be an exception to what I said, because that very much was an idea. There was something about the idea of the Victorian era–a curiosity about the history that preceded that poem, moreso than any image. I’m glad that that poem is in the collection because I think it’s important to have some historical context as a part of the collage, the larger narrative. And because I think that these historical forces do find their way into our lives. They impact us in profound ways. And so I wanted that to be part of the narrative. I know sometimes narrative is looked down upon by poets, but I think stories are helpful and historical context can be very informative for poets.

AW: I have to mention “My White Mother Makes Lemon Meringue,” it’s one of my favorites. The poem also reminds me of the power of images in your writing (“Mother makes lemon meringue / separating yolk from egg white”). In this, the metaphor feels explicit (“the way ocean religion melanin / keep me from my kin”). I wonder how that idea of separation informs the larger themes of “Notes on Resilience”–whether one of the major resiliencies is enduring separation that can’t be reconciled. Do you have like a philosophy on how, you know, how many lines, a stanza should have–is there any symbolic importance to couplets versus tercets, or other visual representations of stanzas?

SJ: To be perfectly honest, for me it’s almost always an intuitive choice. And it’s also very visual. Almost like the way you might judge the framing and the composition of a photograph, you know on paper, or on a screen where to crop. After the fact, I might come up with excuses or reasons for a couplet, for example, two halves of the eggshell, the number two, the relationship, two people, the speaker and the mother. But that last line is just one line: “I lick the bowl clean.” It feels right for that to be on its own, because ultimately the speaker is on her own. You know, there’s this, there’s a sense of loneliness, and also something’s been erased. So after the fact I can create rationale for why it feels right.

I was recently revisiting Audrey Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” And Lorde emphasizes to go with that voice inside that says, it feels right to me, and so I think that’s a perfectly valid way to decide how many stanzas or how many lines in each stanza.

AW: About that idea of the intuitive guiding the visual layout–does that intuition ever change in revision or do your drafts usually come out in a similar form to what they end up being in revision?

SJ: That’s a taboo question, because there are poets who will say every first draft is supposed to be this half-formed thing, and then it all comes together in revision; writing is rewriting. But I think that it can go either way. You might write a poem, and after 12 minutes of writing, it’s done. However, not always. There are some that will take years to discover. So I don’t think there’s one rule, though it can happen that the poem emerges fully formed. I was listening to an interview between Naomi Shihab Nye and Krista Tippett, and Nye was talking about her poem “Kindness,” which is one of her most beloved poems. She goes into this reverie on kindness, and what it really is. And it’s a beautiful poem. In the interview, she reveals that she wrote it all in one sitting in this town square after she and her husband were robbed, and they had no money, nothing, and she was left to wait while her husband went off and tried to figure out how to get traveler’s checks. A man came up to her and was kind to her. After that. she sat down and wrote this poem, and she said it was given to her by this voice in her head and she just wrote it down. And I believe her. I do have that mystical belief in poetry, there are things that can’t be explained. It’s not all about craft or knowing the right form, there’s a lot of mystery to the process. Don’t let anyone tell you different.

AW: So, the question was taboo but the answer was fantastic. I appreciate you sharing like some of the poets that you find your work in conversation with Lucille Clifton. Are there other poets or, or writers in other genres, who you see sort of this work in conversation with or being influenced by?

SJ: I was pleased that in the preface Hope Wabuke referenced Natalie Diaz. I definitely was influenced by “When My Brother Was an Aztec.” That gave me a certain permission to write about family in a complex way that did not leave out cultural traditions and the complexities of being, you know, American and/but also not American.

I’ve really been appreciating Audre Lorde, her poetry. I can’t say that this book was influenced by Lorde’s poetry because I frankly had only read a little bit of her poetry by the time I wrote it. But now I feel a close kinship to her work. I’m reading it now. And I got the big Collected Poems of Audre Lorde. I love her work. It’s a perfect balance of clarity and complexity, with a whole lot of edge. The emotional potency is really off the charts. I think everyone should read more Audre Lorde. Not just her quotable statements, but her poems.

AW: Anything you’d like to share about the chapbook box set project?

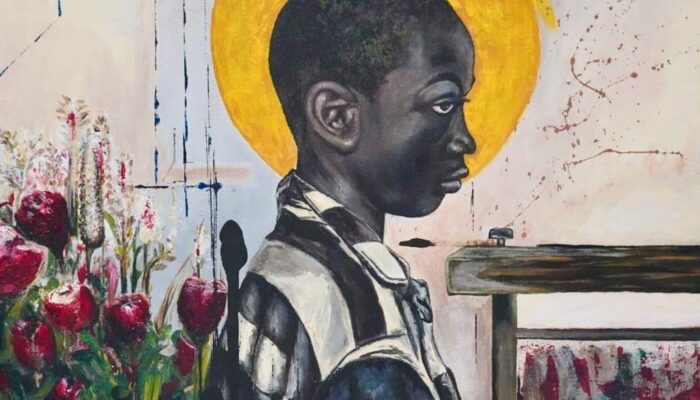

SJ: There’s beautiful artwork on all the covers by the Ethiopian artist Tariku Shiferaw. I couldn’t be happier with the cover art, the painting on the cover of my chapbook. It’s called “Grinding All My Life (Nipsey Hussle).”

I’m just really appreciative of the care and the excellence with which the whole box set was constructed by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani, and also by Akashic Books. They have a wonderful editor, Johnny Temple. Everyone was just extremely professional.

And it’s a real honor to be part of this community of African poets from across the diaspora. I am very excited to be part of that cohort and community. It’s been very profound, you know, to be able to connect with the other poets.

Safia Jama was born to a Somali father and an Irish American mother in Queens, New York. A Cave Canem graduate fellow, she has published poetry in Ploughshares, RHINO, Cagibi, Boston Review, Spoken Black Girl, and No Dear. Her poetry has also been featured on WNYC’s Morning Edition and CUNY TV’s Shades of US series. Jama is the author of Notes on Resilience, which was selected for the New-Generation African Poets chapbook box set series (Akashic Books 2020). Image credit: Jess X. Snow