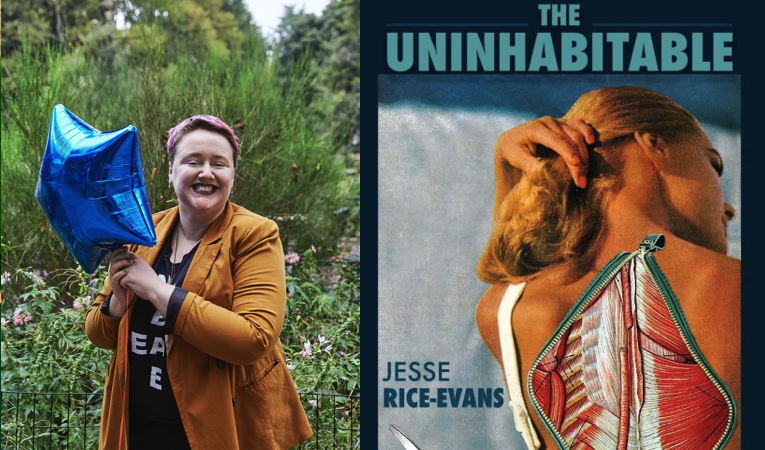

An Interview with Jesse Rice-Evans

I was on my way to meet Jesse Rice-Evans at a French bakery in the contemptuously trendy part of Brooklyn, albeit late, as the MTA could not bear to have it any other way (in my defense, it was a Sunday). Some three odd years passed since my brief stint and premature leaving from the Language and Literacy program at City College where Jesse and I first met as graduate students. What changed during that time? What stayed the same? Can it be discerned with just the naked eye?

When I finally stepped into the bakery, Jesse was sitting with her back to the window, the overcast sunlight illuminating the inked winding of tattoos across her skin. Anybody with tattoos knows the labor of getting one or several. The pain is best described as a dragging of a vibrating knife across the dermis. I asked Jesse why she chooses that kind of voluntary pain despite regular pain she cannot control—the chronic aches, depression, and the medicated or unmedicated fatigue. She smiled and said, “You said it already. I chose this pain.”

The Uninhabitable is therapy for those bodies that endured traumas through lyrical exploration of the subject’s own internalized anger, judgement, and ableist scrutiny of fallible bodies. Evans’ debut collection asks readers to imagine violence and war beneath the skin and tempers it with gentle and forgiving language. In our conversation, I asked about her techniques, mentors, and being “at home” as a disabled femme writer.

—Crystal Yeung

Crystal Yeung: What space does The Uninhabitable occupy and how does it interact with the social climate of body politics we currently live in? What kind of diagnosis is given to it from the larger hetero able-bodied world?

Jesse Rice-Evans: I find this question challenging. Something I want my work to do is that I think is important is taking up space with pride and commitment and holding it so that other people can get into it, too, especially with bodily difference, disability, disfigurement, pain, or augmented bodies of any kind. I think that the level of disconnect culturally between non-normate and normate bodies is huge and bizarre, so I wonder about that representation, like what about disabled bodies is so confusing and upsetting for people? You know, 20-25% people on the planet has a disability, and it’s still a sideshow fest. I’m not able to understand the terror that abled-bodied people feel being near disabled people. So much of the book is about me and my experience but that is always situated in the larger context of my professional and personal and broader socio-cultural spaces. My biggest takeaway is that I don’t understand what is so scary. Unless people are scared about Freudian questions of how my body is fallible and I’m going to die.

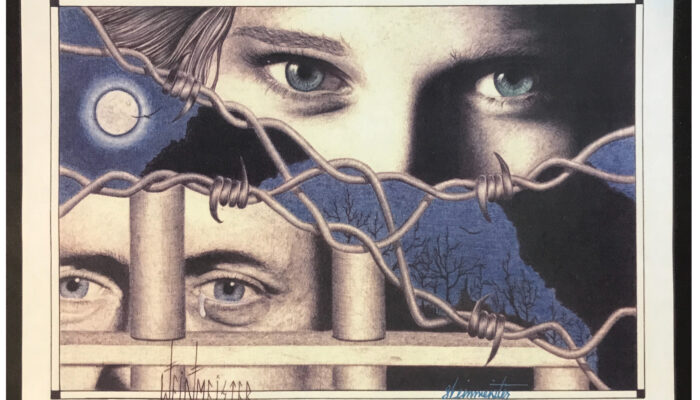

CY: Talk a little about the cover art, “Underneath It All” by Eugenia Loli. Is this an accurate embodiment of your work? And why does it make my skin crawl?

JRE: That’s a great question, Crystal. It’s funny as I was thinking of cover art for the book, I was looking at a lot of places and initially didn’t want something that was super literal that correlated too much with the title. Sibling Rivalry has worked a lot with Eugenia Loli in the past, her work being on the cover of Bryan Borland’s book Tourist and sam sax’s madness. Her images have that kind of gritty, vintage feel to them that I really responded to. So when I was looking at Eugenia’s work on Instagram and scrolling through her work back years and years, this was the piece that reached into my gut and grasped me and informed me that this was the cover. I’m trying to trust that kind of instinct across my work more broadly, that kind of gut feeling of intuition or truth that just stays. I’m super thrilled to get to use it. And I do think it’s creepy! That’s why it might make your skin crawl. We don’t want to see what’s under the skinsuit. People don’t want to go in there. And that fact that there’s lines to specify different anatomical features you can imagine in a medical textbook. It’s really taking from this disembodied context of “this is an abstract objective thing” and shoving it into a human body. I like that unsettling feeling.

CY: How did you decide the chronology of the poems in terms of themes and sections? What was most labor intensive about putting together your collection of poems?

JRE: A lot of it goes back to what I just mentioned about the gut feeling. I almost feel like I didn’t make many decisions about this book. I feel like it informed me the way it needed to be played out and connected. I just trusted that the pieces organized themselves in a way that felt right to me. As far as the difficulty aspect, there’s always the fear of claiming disabled subjectivity which is not what I want to do here, speaking for a group of people with such a diversity of experiences, identities, histories, and cultures. The difficulty for me was articulating my own experiences while still acknowledging the greater stories and work being done by disabled writers whose politics are something I aspire to have and practice.

CY: What is conscious in your specific use of the language of pain, illness, and healing? I notice the naming of a certain kinds of pain, illnesses, and medications—fascia, propranolol, orthopedist. What do you intend for it to do?

JRE: I like to use extremely precise, sometimes jargon-y, language. Part of being in academia is being around all this hyper specific language that is intentionally rendered inaccessible, which is like the ways in which people who are sick and must consistently access care in that they have to know a lot of this language in order to be taken seriously by medical professionals. I think that when so much of this book is written from a space of intense pain and a desperation to heal and feel better, hanging onto the very specific nouns and things that I regularly interact with is like a tether to the world outside my body and sometimes the world inside. You know what fascia is?

CY: I think I looked it up, but please remind me.

JRE: It’s the gunk on your muscles, like a ropey net over all of muscles in your body. One of my pain conditions is fascial, which makes my muscles tangled and stiff and lock up. That’s one of my daily things that I cope with. Being able to point to something in my body that I know is causing the thing or like a central character to what’s going on is reassuring when it feels totally unmanageable.

CY: I notice a lot of the poems look like prose on the page, running from one end of the margin to the other. Is that a decision to eschew poetic forms or are you creating ones as you go?

JRE: One of the main things I was working towards in this group of poems was not over-intellectualizing the language. I trusted that the pieces made the shapes that they needed to make. This is tricky for me to talk about because I teach first-year academic, professional, and technical writing and I talk a lot about this with my students. I’d say “trust your gut” or “develop your writing through your gut” and “try to listen to it and honor its needs.” But they’re all engineers so they’re like “what the fuck are you talking about?” It is a skill that you develop in writing and I don’t know how you develop intuition. I try to just believe the poems and not try to ask them to be something that they’re not.

CY: Who are your poetic, queer, or disabled predecessors and theorists you look to in navigating your work?

JRE: It’s so weird because I do read a lot of poetry but it’s not often that poetry informs my poetry but other forms and types of writing. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has to be up there and I think Eli Claire and Natalie Eilbert has to be up there. Those are the folks I return to again and again with this book. There are many more AMAB and BIPOC writers I am obsessed with these days.

CY: There are references of North Carolina, your home state, and New York City, where you live now. How does the landscape or anatomy of these two distinct places interact with a disabled body? How do you navigate these spaces?

JRE: New York is the only place that has ever felt like home to me and I don’t totally know why. In North Carolina, I never had to think about my body so much. But I go home now and realize that I have to drive everywhere, that there isn’t reliable public transit for me to get out of the obligation of taking myself everywhere. Even though the subway is wildly inaccessible in a million, million ways, I can get on the train, put on my headphones, and listen to an audiobook. I can do that and be on the same train for an hour to get up to Harlem and that is a real blessing for me.

CY: In “Cervical Function/Sub-Occipital Release,” there is a sense of not feeling at home in one’s own body, in the internal sense and how clothes do not fit, overlaid by descriptions of daily exhaustion and malaise—which to my mind mirrors visible and invisible illness. Can you speak a little bit about that?

JRE: Going back to the first question and thinking about how people react to illness and disability in public, invisible illness means being able to pass as abled but being subjected to hyper-scrutiny when you ask for access or when you show a symptom more visibly. For example, I’m thinking about being in class and being on different psych meds and not really being able to not yell at people. Or there are instances where the illness that is invisible becomes more obvious to people who weren’t looking for evidence of my illnesses and that being read as crazy or disruptive or disrespectful, instead of assuming that someone is just having a shitty day or changing their meds. When I started using a mobility aid and I would leave the house, it became a very different public space to be in, wherein strangers come up to you and say they’ll pray for you or give you recommendations for the camu camu juice that healed their cancer or ask really personal and invasive questions about your body when you’re a stranger. Being femme and younger has a lot to do with that. But it’s getting attention that you really don’t want. I just want to be fucking left alone, whether or not I have a cane. It’s very weird to have a bunch of strangers feel like your body is available for commentary. This happens to femme-presenting people in the summer, where a lot of folks feel entitled to comment on strangers’ bodies and with varying degrees of threat or implicit power bullshit happening. But I find a lot of parallels there that are uncomfortable but also maybe a point of connection between abled and disabled people whose bodies are seen as permitted to commentary.

CY: And this is a frustrating process that also happens in clothes shopping?

JRE: Finding clothes is challenging. When I was first developing pain as a regular daily symptom, I had gained a ton of weight after a traumatic IUD insertion. All of a sudden, none of my clothes fit me. It was traumatic. I don’t have a problem being fat. I like it, I like my body. But all of a sudden, the things you’re comfortable wearing suddenly becoming not available to you and being poor and unable to buy new clothes is frustrating. I just can’t take that all at once.

CY: Your epigraphs cite people from vastly different fields, genres, and periods like Antonin Artaud and a shout-out to Kanye West. How do these people inform or relate to a poem or theme?

JRE: I do want to use this question as an opportunity to talk about my unending grief over losing Kanye West to some ugly cultural forces. He has been a creative inspiration of mine forever, since I first listened to The College Dropout album back in 2004. It was a source of power and representative of the kind of expansiveness in creative work that I’ve always been drawn to. It’s been an ongoing process of leaving that behind me, trying not to get into fights with people who have a lot of strong opinions about him—which is mostly other white people practicing anti-Blackness by using him as a target. This is largely me finding my own way to understand that this enormous force in my life is something I don’t need anymore. That’s kind of the way I’ve been framing it in order to feel okay about it.

The poem the Kanye epigraph is in, “ISO Femme Top,” was written several year ago before things got really weird and ugly with him. I thought a lot about taking out that epigraph. When that piece was published in Dream Pop Press, I ask the editors if a caveat can be included about the epigraph. I didn’t want to pull it. I didn’t want to erase the historical and personal connection that piece took from Kanye’s work, but I also felt self-conscious being like a white person using a Black man as an object to deal with my issues around sex and gender in that piece specifically. So it’s been really complicated and difficult but I’m trying to embrace a gratitude for all that he was able to give to all of us, but especially to me, while honoring that people change not always in ways that I would be supportive of. Even though that’s a kind of grief that’s been hard for me to live with.

CY: There is a constant you-character who is addressed, but readers never truly get to see the face of “you.” Are they a lover, a projected version of yourself, the speaker, or a representation of an institution that is causing pain? In “Better Skin,” “you” is regarded tenderly. In “Poison Season,” “you” suffers the speaker’s anger. How does this/these person(s) factor into modes of living—in femmeness, in queerness, in pain, and for survival?

JRE: It’s like you crawled inside the heads of my undergraduate poetry teachers who had a never ending slew of questions about this ”you.” The “you” has always showed up in my work and I don’t know if I can answer who or what “you” is. You hit a couple of important observations about “you” that it is often a projected version of the self or the self of the speaker in various cases or “you” in plural forms, although I do try to use the “y’all” form.

CY: It’s a North Carolinian affect, right?

JRE: Yes, goddammit, and I encourage people to adopt it and to appreciate the cultural values of the places that it came from, which are Black culture and Southern culture. But I do think that sometimes “you” is the public in the spaces that I go into.

CY: Or sometimes it is yourself.

JRE: Yeah, sometimes it is the version of me that is super ableist and judgmental about my body and its needs. Sometimes it’s a figure that I’ve created to police my body, my gender, or how I speak about my experiences. And disabled people get policed like crazy. I was listening to the Disability Visibility podcast hosted by Alice Wong yesterday; in one episode about food accessibility and the activist and writer Shona Louise who was featured in the episode was speaking about her experience in being in the UK and being disabled. She was explaining that there is a hotline that people can call if they think that someone is faking or exaggerating their disability to get benefits from the state. It is very widely used and this happens a lot for people who have more fluid, chronic health issues, like for those who uses a wheelchair one day and not needing it the next. A lot of ambulatory wheelchair users exist and I use a wheelchair at museums and at festivals because if I walk for that long, I’m going to get sick. I don’t want to be exhausted and unable to function. It’s a matter of people figuring the needs of their body and how to express those needs in appropriate ways and sustainable.

I thought it was interesting that you pointed out that “Poison Season” has a rage-y vibe. I can see that in what you pointed out. To myself, it was more like a sexy flirtation with someone that you’re also annoyed with for saying something ridiculous. Like, “Goddammit, I’m pissed off at you. Let’s make out.” So some low-key rage.

CY: With The Unhabitable, you give readers an imagistic, roiling kind of liminality that is all at once excessive and constrained. This liminality is something I see in the collection and the way it is partitioned, from “Genesis” to “The Final One”; in between is a warring of the body and mind, its traumas, histories, and diagnoses. From all of that, what is the antivenom or relief you’ve made in your work?

JRE: I love the idea that it’s antivenom or relief. It really is and I’m so glad that you felt that that was happening here because I’ve always been a pretty cynical yet jolly person. I think a lot of things are funny when it’s probably inappropriate to think so.

CY: For a lot of people, I think those two things need to be in tandem. Don’t you need to have a certain kind of lens to handle the absurdity of the world?

JRE: Right, but there are also parts of me that want to cave to depression and believe in the futility of things, even things that are really important. But then I see the work of disabled activists, writers, and scholars that are generous, curious, thoughtful, and patient. I am so motivated by their practices; if I can do anything that resembles that, I have to do something to bring the practices I find incredibly valuable into my personal day to day life. This is auspicious because my first academic mentor, Katherine Min, is an amazing writer and teacher who died recently because of cancer.

I have spent a lot of time over the last few weeks missing her and thinking through what her relationship meant to me and how it’s affected my life and realizing how dramatically she impacted me, in how I thought about myself, my scholarship, my writing, and realizing how utterly different my life would be if not for my relationship with her as an undergraduate. So while I’m having these feelings of deep grief and sadness for her children and everyone who loves her and not being able to dance and party together until we’re both really old, I’m incredibly appreciative and in awe of how giving she was. Every small thing she did meant an incalculable amount to me in ways that she couldn’t have known that I needed. So I’ve been thinking about that a lot about how to move forward with her grace, her humor, her ability to face something really dark and to be able to find beautiful things along the way. I aspire to center duty and care and the needs of the people I love, including myself, while still being able to look at the world critically and still laugh as much as possible.

CY: What are you currently working on right now? What kind of future work can we expect from you?

JRE: I’m often made fun of by Zefyr [Lisowski, co-editor at Apogee], like “what book are you working on right now?” I have two: one manuscript that I just finished called ACNE. It’s a collection about the body-mind connection. It’s a little lighter in tone than this collection, a little funnier and more self-deprecating in a move towards humor. I’ve started to look at presses I’d like to work with.

CY: So you wouldn’t be working with Sibling Rivalry?

JRE: I asked them about it. They’re awesome and I would love to work with them until the end of time but they encouraged that I use the momentum from The Uninhabitable to seek out other presses that I like and who I would like to collaborate with on the next project. So I’m appreciative of that, the freedom and the encouragement. So I’m shopping around, submitted a couple of places. It was shortlisted for the Metatron Prize for Rising Authors, which was super cool. The other one which I have been tweeting about off and on for many years is about a collection based on the episodes of Grey’s Anatomy, which is an ongoing project that I have to move away from and return to because I can’t just watch fifteen seasons of Grey’s Anatomy. It’s an ongoing project that I will continue to develop. Also, if there are any presses that are trying to talk to me, they can reach out to me @riceevans 🙂

Jesse Rice-Evans (she/her/hers) is a white neuroqueer femme and Southern poet based in NYC (unceded Lenape territory) studying chronic pain rhetorics and femme pedagogy. Read her work in Hematopoiesis, Peach Mag, glittermob, and Nat. Brut, among others, and in her debut collection The Uninhabitable from Sibling Rivalry Press (2019).

Crystal Yeung is an almost-poet and holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the College of New

Rochelle. She received her BA in English literature and was a part of the Language and Literacy MA

Program at CCNY. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in Rabbit Catastrophe Review,

Poets & Writers, Perigee, and TAYO. She is a recipient of the 2017 Amy Award, serves as poetry

committee chairwoman for the PEN Prison Writing Program, and is on staff for Apogee Journal.