On Aldrin Valdez’s ESL or You Weren’t Here

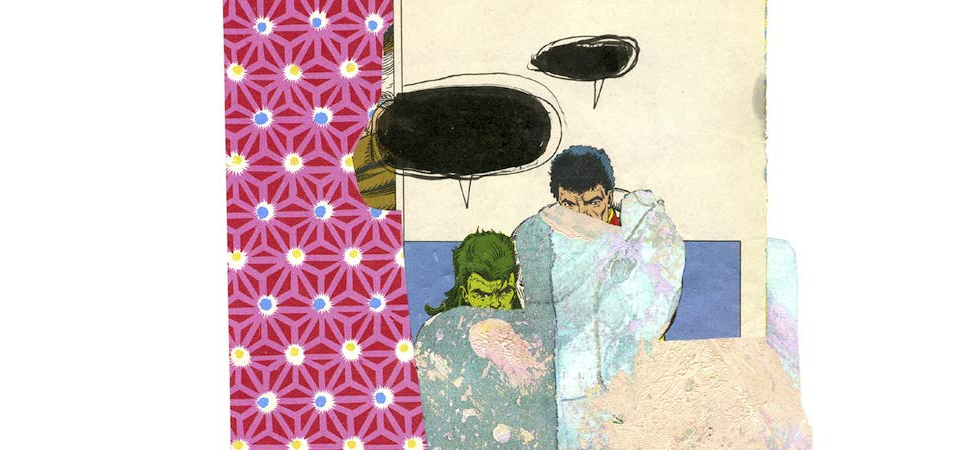

On a neurological basis, recalling memory is often likened to a jigsaw puzzle or a collage of associations. One corollary of this is that memories are not frozen in time, and new information and suggestions may become incorporated into old memories. In a sense, remembering can be thought of as an act of creative reimagination. In their debut poetry collection, ESL or You Weren’t Here (Nightboat Books, 2018) Aldrin Valdez does just that in a diasporic tradition, marked by movements across temporalities, cities, and generations. Their words flit across the page evasively to “eschew a linear and totalizing narrative for the gracious form of fragments.” The queer Pinoy writer and visual artist also applies this description to their poetry collection’s cover image depicting a torso in metamorphosis, as if simultaneously noting the unreliability of human memory.

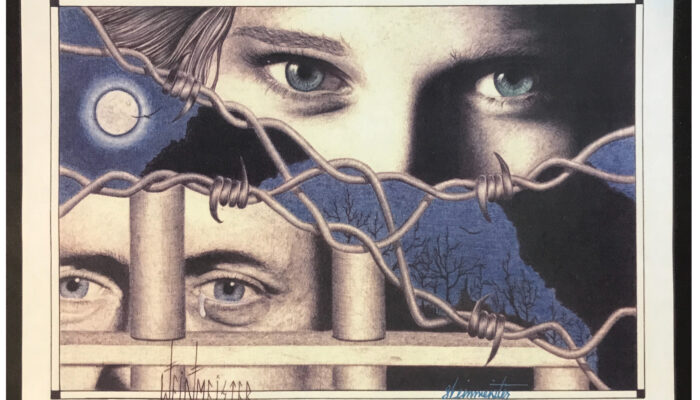

ESL or You Weren’t Here doubles as a love song and lamentation for the Philippines. Valdez organizes the collection into four sections: “ISA,” “DALAWA,” “TATLO,” and “SHUFFLED SLIDES OF A CHANGING PAINTING.” The sections are numbered one to four in the Tagalog language, echoing the Philippine-Catholic doctrine of the Holy Trinity and subverting a fourth “existence” with poems that are numerically shuffled. Valdez’s collection grapples with themes of migration, pain and convalescence, grief and celebration, and languages and bodies that are transformed and translated. Colonial vestiges are indelible in the Tagalog vernacular, as a result of American intervention of Spanish colonial rule in 1898 and subsequent occupation until 1946, which is further examined under the scope of identity and the body, sex, and gender’s mercuriality.

ESL is marked by its dual use of Tagalog and English. In the broader context of multilingual writers, the burden of translation means that meanings often do not pass through the sieve of English as the dominant language. As such, Valdez foregoes translating Tagalog. Their grandmother, or Nanay, does not negotiate with the imposed language in the poem “Tagalog,” which opens the collection:

Nanay once joked that when it came time to move to the U.S.

she’d beg the pilot to turn back. Or she’d jump out of the plane

swim back to Manila.

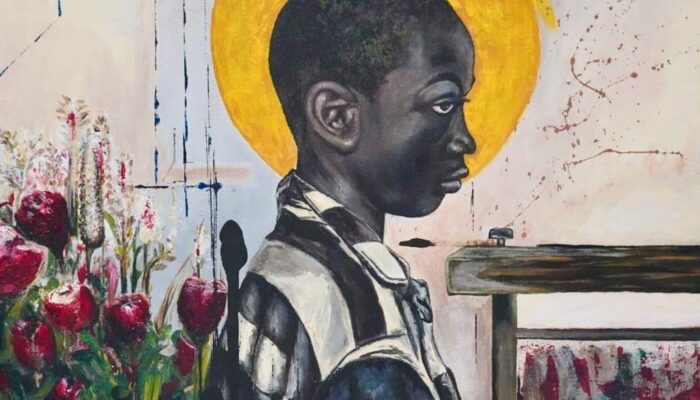

Motifs of water and fluidity run thick in the poem, as “Tagalog” and its iterations (“Sa ilog/Taga ilog” meaning “in the river/from the river”) is consigned in Nanay, who is a kind of primordial fluid intrinsic to the collection’s speaker, a characterized needy bakla (Tagalog slur for “homosexual”). Pain, sickness, and the wide-eyed mystery of youth is evident in “The Albularyo,” where a witch doctor in the Philippines cures Aldrin’s astasis, and in “Purple Gender,” where a white doctor performs circumcision as the speaker’s rite of passage to enter manhood. Remedies are starkly different, insofar the treatment is racialized and even violent: young Aldrin has upset a dwarf witch, so they apologize and the numbness in their legs lifts; to be a man is to have added length, so a boy is cut by white hands. In both, young Aldrin is wordless, small, and unheard. The ailments are different, the distance between Manila and the US are palpable, parental figures and names shift, and each poem—or rather, each remembrance, prefaces with color, the cosmos, or meteorological phenomenon.

From “The Albularyo”—

Remembering is a nebulous blue breathing. There

is this side and many other sides. Tagalog words

filter through with little English clouds attached to

them. LUMALAKAD is a cumulous puff: walking,

across a serrated sky.

…and “Purple Gender”—

In the red room stands a purple gender

a nervous color.

Me. Surrounded.

I remember when I was circumcised.

I counted down to one.

I was not alone but I was without—the right context?

The poems lament a series of losses to sterile whiteness: “I miss my foreskin./Not its added length/but its petal-ness.” There is a fly-on-the-wallness evident in a young person’s precocious and innocent comparing of queer bodies to the petalness of a penis, the phallus as a flower. Newspaper, tabloids, and photographs measure temporality as in the case of “P/PH/F,” where pictures serve as archives and poems as portraits of grief. The poem cites an account of a Filipino man who cuts off his own penis in the late ‘90s, but the speaker cannot figure if this happened in the Philippines or in Queens, New York. As a result, it becomes “a (touch) & go situation.” Their thoughts remain parenthetical, ultimately unsure if the article was in Tagalog or English, and the details are reimagined. This can be attributed to either scenarios: the unreliability of the speaker when memory becomes muddled or the poet taking agency and reimagining the event. Despite the unreliability, there is a sense of reaffirming and proclaiming identity, the only feeling that is certain despite the phonetic voicelessness inherent in both F and P:

Lately I’ve been identifying myself as PILIPINO and PINOY, and

become conflicted as to when to use the terms and, in conversation,

with whom.

[…]

I am PROM the PEELEEPEENS.

I am PAIR, PEARLESS, PACTUAL.

This becomes an invitation to the speaker’s interiority, an inhabitation of both pronunciations. At the same time, the poem discloses inherited trauma and contention with imperialized language from American occupation. Leftover words such as‘kanos (white Americans), balikbayans (repatriate boxes), and jeepney (recustomed or chopped up military jeeps leftover from WWII) make their appearance early on in “Tagalog.”

But what if control can be measured by using the passive voice? There is special attention paid in the act of bearing witness to assault, violence, and shame which are captured by lens of both the human eye and a camera. During scenes of a cruel childhood assault in “Opened,” a camera’s eye is turned upon the speaker’s small nakedness: “They took him unawares./Yes, they took him unawares./Purple Gender in this telling is telling you/they took him unawares into his sister’s bedroom./” The memory is archived and reaccessed by its repeated irregular syntax. “Bakla” (fag) and its other forms like bumigay (to give, get broken or damaged, to come out of the closet) and bading (homosexual) lives in the same poem that has emblazoned in the middle of the page “SHAME./SHAME./SHAME/on you/.” This, and other acts, occur in the home; as a result, the home becomes a site for violence. Photographs and memories meld, as in the case of the brain and long-term potentiation, which is a process of synthesis and encoding memory as a circuit. Perhaps that is Valdez’s extended manifesto of truisms: we are programmed to repeat our perversions and proclivities.

If home is a site of violence, Valdez constructs sex as a site of healing; every orifice, both natural and created, is of pleasure and injury. In my favorite poem, “Sagad,” they proclaim:

[…] O—let my mouth

be a site for feeling!

In Tagalog, I tell you, there’s a word

for this fullness—Sagad: to the hilt,

as in a sword or a screw.

And just like that, violence

punctures the field of conversation.

This is the speaker and their words at the most centered and controlled on the page. Both body and words are celebrated with a lover. Closing the third section with “Sagad” makes sense as the collection opens to “SHUFFLED SLIDES OF A CHANGING PAINTING,” where Valdez invites readers to dip in and out of the pieces. No sequence or pattern of reading is needed thereon as Valdez numbers the titles out of order. Despite the lack of sequence, embodiment is a constant crux of conversation in this collection: their grandmother Nanay embodies their mother, while they embody the space between the hyphen, between oceans, cities, temporalities, and the amorphous body. This is performed through tart and mindful lexical leaps of a young Aldrin as the speaker.

Subjects I often revisit are the act of translation and, as a second-generation Chinese American, living in the hyphen. How do you live between worlds? How do you communicate without meaning being warped or misunderstood? Why does Colgate become the de facto toothpaste brand for the rest of time? (Aldrin writes about the toothpaste in “Purple Gender”). I am reminded of what Coca-Cola is in Mandarin: kěkǒu kělè (可口可樂). Simply kělè will suffice; its meaning can be understood as “allowed” or “permitted happiness.” Suffice it to say, whatever happiness is felt is probably assigned or allocated.

I remind myself that this is a portrait of a hurt youth written by an older self in hindsight and the unreliability of the speaker is tacit. However, I can’t help but want more exploration in the poems, either imagined or real memories, to be cut further by their poems. I want the speaker to ask the gods—the Christian and the Greek variety cited in ESL—how do they square with hurt, inequity, trauma, and being lost in translation? What would a picture of Pinoy masculinity look like if drawn by the speaker’s father? Some poems span over a few pages like stream of consciousness writing, like “Tagalog,” “The ancestral sense of HOLD is preserved in BEHOLD…” “Memory,” and “Sagad.” These poems read full and complete, whereas others (“ESL or You Weren’t Here” and “33”) read fragmented and not articulating a full sentiment. Though I am reading for fuller intent and sentiment, Joseph O. Legaspi says it the best: “But through it all, at the heart of it is a pursuit of connection, of totality.” What have I got but eons and an appetite for transgressive, diasporic work? So I will wait for totality to come as I can enjoy ESL again and again at my discretion and non-sequentially.