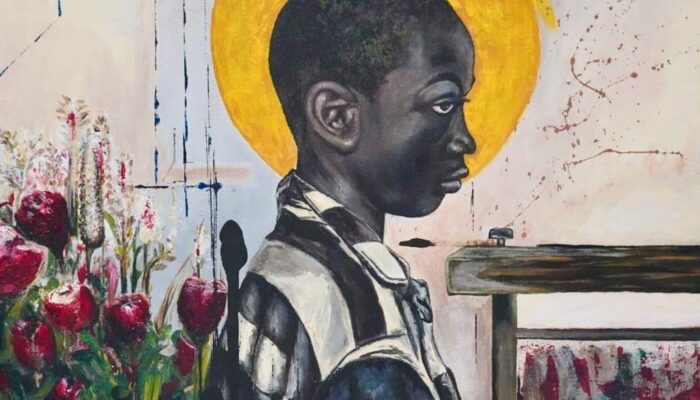

Mother of Yves, Jahmal B. Golden is iconic in our community of creators in New York City. They are brilliant, creative and out-here, dedicated to bringing femme community together. Among many commitments, Jahmal curates Fox Wedding, a reading and performance series in Brooklyn and has work forthcoming in The New Museum in collaboration with RAGGA NYC. I was thrilled when they offered to share with Apogee Journal their collection in advance of its publication. Yves, Ide, Solstice (Easy Village Publishing) chronicles losing at love in triptych-form. It explores the ways in which love (or losing at it) complicates perceptions of self and identity-formation. Yves, Ide, Solstice launches this April and is available for sale online.

From the forthcoming collection, Yves, Ide, Solstice:

lambent

for yasmin

i heard this story

of a pair of old lovers

in florida. the woman

was succumbing to cancer.

in her

boomed thunder and

a constant breaking and resewing.

she was becoming a rag-doll

when her lazy eyed husband

found himself a cure for her illness.

it was a lamp that was meant

to suck the sick out from her – a machine that glowed

with healing rays.

no.

the lantern did not work.

yes.

the lamp did cost a fortune.

all of that to sit and wonder

whether we should all believe

in light as much as george —

even if it can’t cure cancer.

all of a sudden

summer, 2012

suddenly,

my days were made of this —

hot air. bare

chests bobbing. emptying often.

breathless. sudden desert –

savoring each gust like a kiss.

reading scorch marks

on the palms of your feet.

shadow puppets.

mirrors. ashtrays.

constant cold showers,

tea tree oil.

dizzying in bed. plus one or

two. invisible bruises.

humming to myself thinking —

will i ever lose what i have made here?

amethyst

like tethys

she

quenches the thirst.

she

has plenty to give.

filling each glass

with her aubergine dreams.

she

seduces – a curtsey, a twist –

her

days are made

of this.

—–

JDJ: I’m curious about the consolidation of these three sections—can you speak to their conception? How the poems found themselves in each section? How does the triptych support the architecture of your long narrative?

JG: I think it started with my favorite name/alter ego/future child, “Yves,” and how they long for affection tirelessly—a lot of this collection is in their voice, especially the third section of the same name. I like that an “eve” can be beginning or conclusion. This is, in some right, a mirror of my gender and life. I am at once beginning and ending always—a shapeless collection of ideas, memories and intentions. At the very least, that’s what I aspire toward.

“Ides” is in reference to the Roman calendar; presumably, it is the time of the full moon, in the middle of a month. Naturally, it’s situated in the middle of the book—a moment where the speaker realizes that their surroundings are a lot colder than they had originally planned for. Things start to lose color in this section as the speaker become more aware of their cycles. “Ides” is a tongue-and-cheek moment for me, but still a harsh chapter in ones pursuit of true intimacy.

“Solstice” is the period of connecting with another person (or, even, connecting with yourself) where you can affirm and assert things that you can’t justify later. It is the moment where you suspend your cynicism and choose to be generous to another—selfhood and body suddenly both offerings. The only thing I can say in addition is that this is how “losing at love” begins—it is the overextended reach of a tragic host while the other sections are their retracted and empty palms.

JDJ: Can you speak to the imperative for love poetry today?

JG: Confessing love (or love lost, for that matter) is crucial now because it’s so much harder to grab people as they scroll through usual dosages of carnage and corruption. I cannot deny how desensitized this world is—how out of touch we are with our capacity for love.

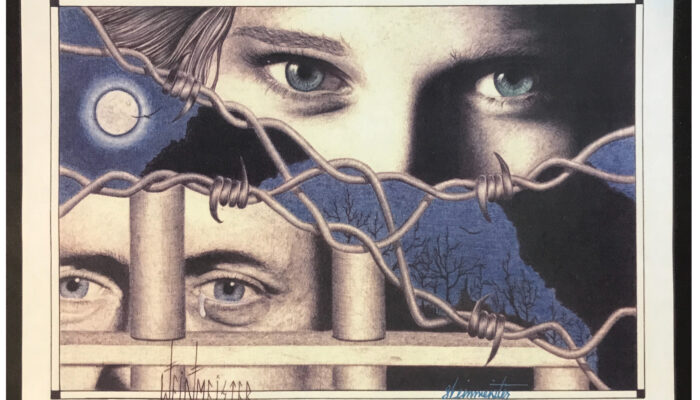

Sometimes I think the language of love has changed or that we have to create a new language. When I began writing about desire I found the words for a feeling I’ve experienced constantly, even since I was little: this feeling of “losing at love.” Pins and needles envelope my body—the physical discomfort that arises with “hurt feelings.” This experience isn’t confined to how I relate to intimate partners. It is just as present when I extend myself to the aching femmes of the world—mothers who lose their children, battered lovers, missed connections, our attempts to escape ridicule or loneliness in digital/imagined/anonymous spaces. The second to last poem in the collection takes its title from this sentiment.

JDJ: The brevity of “amethyst” and its ending with a flip slant rhyme is very tasteful—it carries an echo of Dorothy Parker—what catalyzed this moment in your writing? How did you know this poem was done?

JG: There is this moment for poets where you truly gag yourself with a thought and the easy part becomes laying it out in the daylight, trimming stray thorns and branches. There is this moment for poets when it is absolutely fun—bringing on sudden laughter or a well-deserved drink. Suddenly, your work for the day is done, so you put the pen down, undress and dance naked for a while.

I feel like Dorothy Parker made herself chuckle quite frequently—I’ll gladly take a glass of what she’s having.

Writing “amethyst” was a divine experience with an even more divine muse (though she hates the word in reference with herself). I was looking at my friend and former employer (also a personal inspiration of mine) as she marched slightly ahead of me towards the cafe we’d be meeting at for the day. For all of us who know this person, and her effortlessly alluring gestures / posture, we know how much space and attention she commands. To me, she attracts love the way amethyst is said to. This poem is for her.

JDJ: Can you speak to the power dynamics depicted in “the last one”? In what ways is this text subversive of an apparent norm in Poetry publication to assuage white guilt?

JG: I almost named this piece “show me the receipts”. “the last one” is a poem for the femme who returns to sex as a tool of self-harm, repeatedly. Femme pocs may drag whiteness and misogyny through the mud in these prolonged cyber-crusades but that doesn’t stop them from becoming willing victims of the same ol’ carry. It is exhausting. I, for one, keep a lot of my chaos to myself because I am neither saint, nor prophet.

JDJ: Can you speak to your writing processes—I’m curious how you conceptualize your writing life in the context of your life as an artist of several media.

JG: My thoughts are mostly in verse. Some sentiments I need to capture and verbalize instantly. Other thoughts I leave to ferment. The written thoughts are the poetry. I evoke the fermenting thoughts through performance.

I am a very dissociative person—I leave this world behind when I conceptualize, materialize and perform. I, oftentimes, act out scenes I’ve left brewing in my subconscious when I perform. It is a meditative act, like astral projections. I know I am the same, but everything else around changes. It is like discovering a labyrinth you’ve erected.

My 2D works (particularly sculpture) are like extractions from the walls of my subconscious. I use this motif of crystals and decaying wood in some of my pieces because I envision the body as ship wreckage or a geode in my “self-excavations”. When I remove artifacts that prove that I once existed, they are crystallizing and, once they’re displayed, they are decaying. The sculptural works mirror text and the worlds I document when writing.

In fact, not only does my work regularly reference the writing, but it solely exists because of the written work. All that to say, my writing process is the same force that fuels my exploration of other mediums.

JDJ: I know you are a model—obvi—to me what’s so fascinating about modeling is this intersection of hypervisibility and invisibility—that, as a model for another’s designs, you are simultaneously both. Might you see a relationship between this paradox in modeling and poetry?

JG: Oh, wow. I have to make this distinction so often; it’s no great matter to do so. I am not a model—that would imply that it is a pursuit of mine fueled by my unabashed passion for modeling. I am a person who has modeled and will likely model in the future, but it doesn’t fulfill me the way dressing / reinventing myself daily does—doesn’t sustain me the way other mediums do.

But I do have plenty of thoughts on the matter of hypervisability and invisibility. I hope to exist between the two poles in my poetic practice as I do in my waking life. I don’t want to be tokenized for how I look or where I’ve been , but I know that a lot of things rely on context—how I look definitely will change how I’m read and why this work is important or interested (or whatever).

SIDENOTE: This is a factor that deters me from some of the self-portraiture work I’d like to experiment with and I’m working through it.

Jahmal B. Golden is an artist currently living in America. As a self-identified femme POC, they are constantly finding new ways of conveying their intersectional existence through their creative abstractions. Their dominant medium is poetry, though after participating in an interdisciplinary performance/installation curated by New York artist Yulan Grant at MoMA Ps1, they began experimenting with performance as a mode of testing out concepts they’d investigated in their written work. They spend most of their time pondering the pendulum that swings between ‘nature’ and ‘grace’ – measuring the predictable force that propels them back and forth in daily meditations. Golden’s current exhibitions include MoMA PS1, The New Museum and ArtSpace Mexico.

Photograph by Cassandra Church.