Apogee Journal Poetry Editors, Muriel Leung and Joey De Jesus, sit down with Saretta Morgan to discuss performance poetry, working across different mediums, and why “being published—speaking publicly—has a political weight.” An excerpt of Saretta’s larger work, “(Auto) Index” is now available in Apogee Journal’s Issue 07.

Muriel: We’re so excited to publish an excerpt of your larger work, “(Auto) Index” in Apogee Journal’s forthcoming Issue 07. In particular, we’re thrilled to see this in conversation with other published excerpts of this project in Tagverk and The Felt. What is it like to see excerpts of this larger work in print and on electronic platforms? What do you hope the reading and interactive experience would be like across each presentation?

Saretta: My first thoughts about seeing the work in different places revolve around relationships. I don’t contribute work blindly, so when I think about this piece in Tagvverk, The Felt, Apogee, and soon Aster(ix), I think about the experiences I’ve shared with the people behind the journals.

I remember walking into Sweat Pea Cafe in Tallahassee and having a warm and sincere-feeling conversation with Steven Perez of Tagvverk, who was behind the bar. We were strangers at the time and in most ways, still are. The following fall, he reached out to me about submitting work for the journal. I didn’t feel like I had anything to share, but I knew that I wanted to publish with him because it felt like a way of picking up our initial conversation. Not a thematic continuation, but the exchange of mutual respect and generosity of thought. Months later when I finally got together some pages to offer them, I was honored by the care they took in editing my work. The space for conversation that they opened up, and the patience they exercised in an attempt to understand what desires and visions I had were helpful for me in thinking about my relationship to the project. That’s only one example. Each time, things unfold differently, but for me, publishing is about care and conversation, and I’m always honored by opportunities to have those exchanges with people who feel similarly.

When I started this project, I felt strongly that I was writing with the experience of a book in mind. Which is not to say that I wanted to publish and distribute it as one, but that I thought about things like the feeling of paper in my hand, the positioning of a book in my lap, the distance between text and my face, and the physical sensation of progression through something bound—the distribution of weight from one hand to the other.

There was a mental hurdle I had to clear before I could open up to the idea of publishing this particular piece in journals, but once I did, it became very exciting for me to see the work in different sizes and formats, and to consider, for myself, how the experience changes through different material decisions. For instance, at Tagvverk, they were able to hyperlink a Hortense Spillers lecture and music videos, which provided a wider experience of the work—an experience that more closely resembled the circumstances under which it was created. In The Felt, a print journal, I only gave them one page, the first page: “9.30.2016 / Boris Gardiner’s Every Nigger is a Star,” which is also a musical reference, but without hyperlinks or other pages of the text to rely on. The experience becomes more focused.

It feels very appropriate to me now to see sections in various journals. The work is sparse and depends on accumulation over time and on the willingness of a reader to accept the deferment of sense-making. Perhaps indefinitely? In a way, publishing in a dispersed fashion mirrors that aspect of the text. I’m starting to wonder if it should only ever exist this way.

I don’t feel a desire for any particular reader experience. This work is very open and I give a lot of that power away. For instance, in the case of Tagvverk, Apogee and Aster(ix), I didn’t choose which entries to publish together. I passed along some things that were available at the time and allowed the editors to cobble together what they wanted. What’s important to me is that there’s space for imaginative leaps to take place around/between the entries, and for that reason, I’ve remained committed to certain aesthetic choices that remain constant regardless of the publication.

M: I love the way you talk about the experience of the “book” as something that is both conceptual and also very material at the same time. I think we often think of the book as only something that exists in paper form, but it is fascinating to see how the experience of reading on paper can translate across different media. Additionally, I think of how much professional pressure is placed upon the publication and distribution of the book. There’s a certain social and cultural value placed upon a certain way of publishing and disseminating one’s work, which may inform how one creatively interprets their work. How do you think this particular project engages with the expectations of the professionalization of art-making in addition to your instincts towards craft? When are there harmonious moments? When are there contentions?

It also seems like collaboration and conversation is important to you in building relationships with publishers. Do you find that building these relationships mitigates the power differential built into the publisher and author relationship? How has this relationship panned out between you and Apogee Journal?

S: As far as harmony and contention. I guess I’d say that for this piece, as with all of the work that is published anywhere: what’s harmonious is what you’re able to see. What has survived the process of being made public, even if the terms of that survival aren’t yet clear.

I don’t hope to engage expectations in the marketplace; I’m not yet at the point of making work with a public in mind. When I make things, it’s less about communicating interiority to others than it is about translating what I believe myself to understand into physical material, and watching that process happen. For me, this means that I don’t publish a lot. And right now that’s okay.

I understand that for some poets, poetry is a livelihood. For many others it is a desired livelihood. I’m not in that place. Not because I have a spectacular alternative (yet!) It’s mostly because my relationship to language and making is still too fragile or too unknown for me to imagine leaning on it for survival. I hope that doesn’t sound self-disparaging. It’s not.

Recently a friend premiered the film Icaros: A Vision, which his wife began after receiving a terminal prognosis. Last night, he gave a talk at the Rubin Foundation on his experience of moving through illness with her and moving through the life of the film. One thing he talked about that resonated with me was around allowing pain to be an aesthetic experience, which is in opposition to our culture of anesthetizing everything. From the first time they looked at the scans of her breast cancer tumor, they were able to verbally acknowledge that the visual representations were beautiful objects (both in fact and in possibility) and that the scans had a moving effect on their bodies and emotional landscapes as such. That’s the kind of space I want available to me while I’m working. To be able to spend time with things that are awful—the devastations out in the world as well as the tightnesses in me—and see all of the things that they are/can be. And to be moved by that.

If that sounds simple, it should. What I don’t want to sound is romantic, because I say this all as someone who has dead-ass considered anti-depressants many times. But I want to foreground my view on craft: it’s not always what one sets out to achieve or what we imagine will pose a critique or opposition. It can be a map of what’s already happened. Little wakes trailing the navigation of our own particular pleasure and pain. And by that, I’m referring equally to the choices made when we sit (or stand) to write and to the ones made while moving through other parts of the day.

Building relationships with publishers is important to me insofar as publishers are people with whom one might have a conversation. My relationship with Apogee has spanned years. My introduction to writing was as an undergraduate at Columbia. I would go into the creative writing department for cookies before class and I remember when Melody Nixon, who worked there as a graduate assistant at the time, told me about the journal she was starting with other MFA students, and why they felt it was important. The journal itself (the idea of journals, even) was abstract to me, but here was this person who had existed physically in my life in a very small-talk kind of way, and then out of the blue one day, I found that she was saying things that had real impact on my understanding of the literary world and my position in it. Things that none of my writing professors at Columbia could’ve (or would’ve) said to me. Apogee didn’t become intelligible in my life as a journal at that point, but it was a catalyst for another kind of interaction.

For the past year, Joey has been the physical embodiment of Apogee for me. We’ve read together, we’ve complained about shit together, he’s been a guest in my home. In a way, being published by Apogee is my sense of being a guest in his.

Of course there is also power. Being published—speaking publicly—has a political weight. Publishers get to decide who can flex their weight and how. I wouldn’t say that having relationships mitigates that differential. In some ways it might obscure it. For me, the most helpful thing has been trying to maintain a strong sense of my possibility as a person and as an artist independent of access to power in the ways it’s recognized. Making sure I continually ask myself what I need, as opposed to choosing between what appears to be offered.

There’s a passage from Le Corbusier’s “Argument” in Towards a New Architecture:

“The primordial instinct of every human being is to assure himself of a shelter. The various classes of workers in society to-day no longer have dwellings adapted to their needs; neither the artisan or the intellectual. / It is a question of building which is at the root of social unrest of to-day: architecture or revolution.”

Often “the table” is used as a metaphor for power and decision-making. We say, “who are the voices at the table.” I’ve not understood the table. Is it in an office building? A restaurant? Some white dude’s kitchen on poker night? (Maybe mystery around the imagined location is an intentional barrier.) Regardless, I think a house might be a more appropriate metaphor to build out. Because 1) it’s real estate, which people fight more fiercely to secure, and 2) because the table assumes more intention, cooperation and collective knowledge on the part of participants than I believe is likely.

The house, depending on its organization, facilitates or obscures relationships that occur within it. A house provides a wider setting for observation. For questions. Not only who is allowed in the house, but in which rooms? What’s happening in the attic/cellar/garden while the family circles around the table? How does movement occur from one room to the next? What view is possible from one floor verses another? What feeling is possible in the walk-in closet as opposed to the balcony? Maybe even, where is the greatest potential for pressure/pleasure/pain located—can we track the accumulation and displacement of those?

A lot of babbling to say that my understanding of power is that it is structural, and new kinds of relationships require well-thought-out and intentionally built spaces. In my experience, those spaces are small and exist within a larger set of circumstances or institutions (friendship with a co-worker, friendship with my mother, gardening alongside the home-owner next door, community organizing with veterans, making books with the Belladonna* Collaborative, 501c3). Maybe that will always be the case, the important—and pleasure-filled—thing for me has been intentionality about where things meet and how. I say pleasure-filled because I want to acknowledge that the authorship of space is explicitly an exercise of power.

Joey: Saretta, I’m curious about this transfiguration of the body into somatic landscapes—I think that comes across beautifully across “(Auto) Index” entirely. It seems as though you forecast a contemporary climate, one in which poetry is valued by what one is able to see, not by when it moves. Are you implying a norm among contemporary poets? One in which poetry is market-tested? Do you craft in a sort of geosomatic time?

Also, hold up. Do you think your relationship to language and making will ever be less unknown, less fragile? Every time I’ve felt as though my relationship to my language has become more known, it has been lowkey traumatic. What I mean is that some drama rears its demon-face and I feel wiser though triggered. How does that move within you? That, like, impulse to make your relationship to language less unknown?

S: I wasn’t implying a norm. I was responding to Muriel’s inquiry about my engagement with professionalization, which I see as being only one movement in poetry communities among many. But yes, for those who choose poetry as a profession, I’d say that whether or not a publisher is willing to invest in one’s book is a significant factor in how easily one appears legible as a poet and can find/attract work. That’s something we talk about in Belladonna*—the material impact of publication on an author’s life. We look for work by poets who are doing challenging things with language that might be difficult to publish elsewhere. I imagine similar conversations go on at other micro-presses.

With regard to transfigurations/somatic landscapes: I’m very honored by that reading. That’s something I think about often. And since I was so long-winded earlier, I’ll respond by gesturing to two things.

A quote from Harriet Tubman, which appears in Cedric Robinson’s Black Movements in America:

“I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person now I was free. There was such glory over everything. The sun comes down like gold through the trees.”

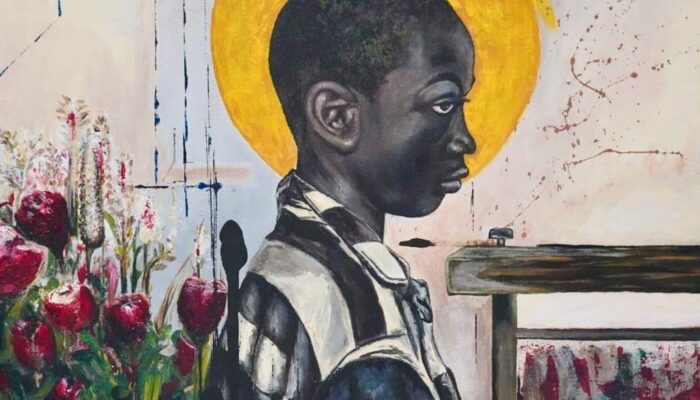

And this painting from the artist, Torkwase Dyson:

Strange Fruit Dignity in Hand (2015)

When I look at Dyson’s paintings, which I read as representations of Black bodies, I try to imagine the kind of language that would come out of that particular visualization of the body. And maybe in that way, transfiguration of the body is related to in/stability of language and fragility of understanding. Like, as my perception of my body (and bodies generally) evolves, my understanding of the relationships between myself and others/objects can change, and new kinds of language are needed to hold those interactions.

In any kind of meaningful relationship, there is an accumulation over time. I don’t feel differently about my relationship to language. Things become less known and more known simultaneously. As in, moments of realizing that I have been mistaken are also moments of knowledge. The writer and artist Youmna Chlala said to me: Erasure is a mark. It’s cumulative. And I think that’s a perfect way to think about it. As time goes on, you can only know more.

Andohmygoodness yeeeeeesss. It can be so traumatic. Holy shit. But one thing I’m realizing is that it doesn’t have to be.

A few weeks ago, a friend and I spent half the morning in bed having a conversation that I later came to realize was about sentences. And during that time, something I’d considered fundamental revealed itself as an apparatus. Later on in the day, I was alone reflecting on the conversation, and I was shocked that I hadn’t been devastated. But I think it was due to the fact that the conversation was so… felt. Like, not in a sexual way, but there were bodies and there was deep laughing and touch and curiosity, and that dynamic corporeality was what the thinking moved through.

So I guess more than I want a fixed understanding, I want to know more about how disruptions in understanding move through me under various conditions. Does that make sense?

M: This makes total sense. I definitely want to echo the sentiments you and Joey express regarding the relationship between language and trauma. I wonder if the triggering comes from not just compelling oneself to remember and record but also from modulating one’s body, voice, and actions so that this trauma is legible to another. As a survival mechanism, this is how you reach out, to touch and be touched, right? To articulate fury or grief? To understand your feelings as not just singular to yourself but sometimes shared? For me, I struggle with an urgency to write it but also the sense of loss that follows. Have I compromised something within me to make this experience hyper-clear? Why is the act of writing always such a perpetual movement between pleasure and pain?

I love your offering of the term “accumulation over time” to describe your relationship to language and trauma, which shifts the focus from “legibility” to aggregate forms of experiences and feelings. I think this gesture allows for the writing of textured experiences that acknowledges structures of power without feeling beholden to them for definition. How do you compose and structure this sense of “accumulation over time” in “(Auto) Index”? How would you describe the trajectory of this project as it unfolds from beginning to end? (And where is the beginning and end for you?)

S: What’s interesting to me about the formatting of “(Auto) Index” as it appears in Issue 7 of Apogee is that it suggests horizontality in the text. As opposed to any one section leading up to or following another specific section, movement feels possible from any one point to another. The beginning is wherever one enters. In a way, I experience the beginning as wherever I leave off writing in this piece on a given day.

I’ve been reading Renee Gladman novels this summer, and now I’m reminded of her narrative impulse in To After That (Toaf) “to move and go nowhere,” which might be the impulse in all of Gladman’s writing. Yesterday, I was talking about Gladman with poet/photographer Ariel Goldberg, and they said, “When I finish a Gladman novel, I don’t feel as though I’ve read a book.” That’d make Gladman proud, I think.

I feel a similar simultaneous progression/stalling in “(Auto) Index”–: that because there’s no unique beginning or end, the trajectory is continually under construct(ion/ing). A lot rests in/on the formal choices. I’m interested in the pursuit of heterogeneous yet nonhierarchical space. Not saying that I’ve achieved this (or that it’s achievable), but the goal is/was to move toward a structure in which all of the content might assume equal value with regard to narrative potential.

There’s a show of contemporary Japanese architects at MoMA right now, and I think this concept is gorgeously demonstrated in many of their buildings.

For instance, in Toyo Ito’s Tama Library, each floor is broken up into a fluid network of compartments through intersecting arches. None of these compartments present themselves as primary. Yet, because the intersections are not uniform, each compartment has its own particular specifications, which perhaps lends it to certain uses over others, but at no place in the building would one have a sense that they are experiencing a more (or less) significant architectural moment or that they’re being guided toward a central space or localized element. Also, the arches don’t direct the programming of the space (for instance, a series of stacks or an arrangement of tables and chairs might flow through several archways or use the archway as a boundary). Rather than impose an organization throughout the space—as solid walls might—the arches provide a multi-setting where organization can occur.

J: Just going back a little, I love how you discern aesthetic from anesthetics and was hoping you could speak a little more to this. See, I’m struggling to see the difference between the two. Your experience at your friend’s screening certainly moves me, but it raises this question in my mind: is beautifying curative or is it another form of anesthesia? When I read work that features aestheticized suffering, something often feels insincere, though I’m not sure what… What are your considerations around aestheticizing pain that results directly from acts inflicted upon the body and how are those concerns different from writing into other sources of pain? Is crafting innately aestheticizing or do you detect differences? Often, I wonder if the aestheticizing of violence illustrates some type of luxury; or rather, in light of acts like Kenneth Goldsmith’s at Brown, I wonder about aestheticization specifically in relation to the suffering self, the suffering other, and how it functions as a tool (sticking with your metaphor) in the house of the master. Is allowing oneself to derive beauty from one’s own suffering giving in or giving up? (Or do i just need a hug? lmao) I’m a pessimist.

S: Pain doesn’t need to be aestheticized. It’s inherently so. And by Aesthetic, I don’t mean beautiful or pleasing. I mean that it elicits sensation whereas anesthesia masks sensation.

In the case of my friend, he and his wife weren’t beautifying tumor in that instance. The visual they witnessed was a medical rendering—one that many people might look at and only experience fear and resistance. I’m not saying they did or didn’t also experience that. I’m suggesting that moments of emotional intensity are charged in various directions simultaneously. And that an important part of my experience as an artist has become finding ways to hold all of those vectors for myself at once, while remaining intact.

There’s a short essay from David Levi Strauss, “The Documentary Debate: Aesthetics & Anaesthetics,” where Strauss traces a relationship between attitudes in art criticism and chronic pain as an epidemic in the United States. The end of that essay has stayed with me: “The Aesthetic is all questions, disequilibrium, and disturbance. As with all other parts of the allopathic complex, the anesthetic only masks symptoms; it does nothing to treat the root causes of pain, to trace it back to its source, give it meaning, or counter it with pleasure.” What that has meant to me is that aesthetics (to include quality hugs) provide for a map through which one might begin to construct meaning.

I don’t write things down to make them beautiful. I write them down so that I can see them. And while doing so, I try to maintain an awareness that I’m not only looking at my pleasures/fears/ideas. I’m also looking at how those impulses are mediated by the particular material (to include the history of the material) I use to represent them.

If I had to choose between aesthetic and anesthetic (perceiving and not perceiving), I’d say that anesthetic is the master’s tool (writes she from a just-bolstered Percocet cloud!) in that it prevents us from registering and tracking what’s done to us and what we do to others/our environment.

When I mentioned power and houses earlier, I knew that a reference to Lorde would come in. I feel very careful with her words. They’re true. What cautions me is the inevitability often assumed in their interpretation. Tools exist alongside materials and within conditions of possibility. None of those things are fixed in their position. Depending on who/where/when you are, the potential of objects and processes can change.

J: Can you speak to your relationship and experience using mixed media in the performance of your poetry? Do you see yourself using mixed media in the performance of this work? If the authorship of space is an exercise in power, do you see mixed-media work as disruptive of the architecture of “the reading” space?

S: What will be disruptive depends on the particularity of the place. My experiences are within a narrow range of reading spaces, and I don’t use media a lot (though as I recall the night we met, Joey, we both used video/visual projections in different ways). I don’t think it’s ever the fact of multimedia that makes a difference, though by altering the way a space is used, one might come to realize new things about the potential and limits of the existing architecture.

Media (I’m thinking of video and audio recordings) in readings is becoming very popular. Particularly among readers who aren’t present. It’s been interesting to watch how the recording stands in as the person. In most instances, not much changes. Audiences even talk back to the non-present reader.

It takes a lot less than multimedia to change a space. Last week, while we were all feeling very acutely the impact of state violence on black and brown bodies, Erica Hunt sang during a reading at Pioneer Works. I wasn’t there, but when poet/friend Christina Olivares told me about it, she said: “Erica moved something.” And I believe her.

I’m also thinking about Cecilia Vicuña and how her readings feel more like vigils than performances to me. Her observance of the moment and engagement with the energy of the people in it opens a door to another kind of experience. Once, all she had to do was clap her hands. She discusses her approach to performance in this video. For her, performance is largely about the practice of detaching from ego, which is an exercise in power that we don’t see often.