Publish, Perish, Other: A Talk-Back (Part 1)

Apogee Journal Poetry Co-Editors Joey De Jesus and Muriel Leung chat about their anxieties stepping into the editor role, their thoughts on the state of literary publishing, aesthetic, subjectivity, brujeria, hybridity, and dead things. They pop off. (you’re welcome).

Muriel: Joey, I’m interested to know how you came to work for Apogee Journal? What informs your commitment to this literary space from its founding until now?

Also, of all the literary joints in this town… what brought you to poetry editorial work? What goals do you have for the larger literary community as well as your own creative work through editing poetry?

Joey: The story of how I came to work for Apogee is maybe kind of boring. The fun part is that the marvelous editors of No, Dear Magazine invited me to participate in a reading they’d put together at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and I was like, absolutely.

My mother had been complaining that I never invite her to readings. So I was like, come to this one mom! I mean, the Nuyorican Poets Cafe means something in my home. I figured it’d be perfect. It was also a good opportunity to prove that I wasn’t just out here—on stage—talking shit about the family.

Being the thoughtful person she is, my mom brings several meaty empanadas for the friends in attendance. She also provides me with a steady supply of drinks from the bar, all the while warning I might be getting a little sloppy. The lights dim & here we are, munching ever so softly on empanadas in our foldy-chairs when Mahogany Browne gets up on stage and drops the house. I am somehow expected to follow her.

I’m like…

Somebody, anybody drop a house on her ~ Lirael

She leaves the stage. I turn to mom and my friend Caitlin, and whisper I can’t follow her, but I’m already tips and volume-control is the first thing to go. Everyone hears me panic. From the shadowy recesses of the audience behind me, my baby sister loudly deadpans a long, yeah…

So, whatever. I get up on stage, do my thing, feel real weird and whatever.

This night is also the first time I hear Julia Guez. Her poems communicate this rare effortlessness that I am very envious of. I really don’t understand how she arrives at it. Cuz, I’m like tinker tinker tinker and what I’m left with is a mess. So, after the reading, I go up to Julia, just to be like, I was really moved by your work and to like, talk a little, you know? Now, in the background, my tiny mother is teasing me because I’ve mispronounced Julia’s last name. She was just like, Joey, what kind of Puerto Rican are you? and I’m like, Mom, this is why I don’t invite you to things! And that was when Apogee‘s Melody Nixon approached me and invited me to apply for the position.

Truth is, I never really wanted to be an editor.

I didn’t want to be an editor for several reasons:

- I’m very judgy and don’t like a lot of poets, so the thought of navigating the various and nefarious literary spheres of NYC to establish connections really repulsed me. I’m just a Smeagol grimacing from the shadiest corner at weird literary events… like, in a cloak. I’m literally always cloak-on-cloak these days. I witness careerism and it seems like such a distraction. There is such a concern over prestige. Aversion. Averno. Party at this press, party for this person, mediocrity, let’s salon somewhere near NYU, etc. I’m not interested. I have my community, and it is one not wrapped up in lit world nonsense.

- On this tip of like, the various literary spheres of NYC: I was deadass tired of finding myself the only non-white person on a reading roster / in a room of poets. The alt-lit scenes, the MFA readings circuit–I never wanted to mold my voice to fit into those predominantly white spaces. So the thought of putting myself in those environments to search for what I perceived to be talent seemed potentially unsafe.

- I did not and do not want to find myself stepping into the role of a gatekeeper.

- I worried that being an editor somehow detracted from my merit as a poet; that I would get published not because my work was good but because I was well-connected. Now, I’m like, merit is a myth and I don’t give a shit if my work comes out tomorrow or ever because I’m writing and that is all that matters. If I really need an audience for whatever reason, I can just post poems on social media & test the material.

To me, being a “Poetry Editor” meant being complicit in all of these anxieties. It was the idea of building a platform to surrender to poetry that sold me. I thought, if I can use this platform to shine a spotlight on poets whose work I admire then, whatever, I’ll do it. Not for the sake of community, but for the sake of the craft itself.

Initially, Apogee felt like a low-stakes space where I could just build without fear. But that has since changed… You know, if a shadow can puppeteer an entire government, I’m like, scadoot! maybe I can do the same with the literary communities from which I’ve found myself excluded. I’m done fighting for inclusion. But I’ll never not fight to tear down the oppressiveness and elitism of a “lit world” status quo. Anyone who knows me knows that if I’m really not about you, I will drag your wayward soul through the nether-realm mud into oblivion b/c that’s where I live.

Okay. Now it’s ur turn to answer that question. But since I’ve spilled my anxieties all over the floor~ Have you ever felt anxious about stepping into the role of editor? If so, how are those anxieties different from the expectations you have of yourself as a poet? If this is a dumb question, let me know~

M: Joey, I was telling someone the other day that I’ve always lived a contentious life and don’t know if I would prefer it any other way. And I believe a lot of that bleeds into my role as Poetry Co-Editor with you at Apogee Journal.

When I say “contentious,” I don’t mean that I’m flipping tables (as much as I’d like to).

I mean that I was selectively mute when I was five and didn’t realize how much that mattered to people around me. As a non-native English speaker, that fall to silence is not uncommon. But I remember adults and other authority figures feeling particularly affected by this self-selected silence, which for me was a protection in a strange and sharp place. After school one day, I tried to go back into my classroom to retrieve a backpack I had left behind and couldn’t understand why my teacher was so infuriated by my inability to ask for permission. She grabbed me several times and shook me, demanding to know where I was going. I stared her down without sound. This experience taught me that resistance could take on multiple forms, which is how I feel about poetry and its possibilities.

As for my role as an editor, I’m always aware of moments of impasse, particularly given what has transpired over the past year in poetry–poets in positions of power being outed as perpetrators of sexual violence, the violent seizure (and consequent erasure) of black bodies in the name of conceptual poetry, etc. What do these events do to poets who belong to the communities directly affected by this assorted violence? I’m against amnesia, of forgetting for the convenience of forgetting. I don’t have any desire to witness the same hurts reproduced year after year. There is a good amount of social and literary responsibility to this role that extends beyond the publishing realm. So of course I’m anxious!

Joey, I think I experience the same anxieties as you about assuming a role of authority when it comes to determining aesthetic representation as an editor; to be one of those “gatekeepers” as you’ve said. All my life, I’ve moved out of positions that exhausted their radical potential for me. I have no desire to be in a position of power for the sake of that power. But I do chase after possibility. I long for spaces where resistance can look as loud or as quiet as it wants to. With that in mind, I do try and fulfill my role as editor with both wariness and a desire to destabilize what editorial work can look like. I think it means paying attention to what’s around us, to experiences that have been historically marginalized, and the immediate present.

As a literary journal with an explicit focus on marginalized voices, I think we at Apogee have to especially critique diversity politics; to work hard to not be subsumed by the “melting pot” theory. Morgan Parker in “Reports from the Field: White People Love Me: Dispatches from the Token” and Loma (Christopher Soto) in “The Limits of Representation” both penned essays about the contentious nature of diversity politics, describing how publishers gravitate only towards a handful of visible writers of marginalized identities and pat themselves on the back for having fulfilled their diversity quota for the issue. I want to keep celebrating writers who have gained visibility oftentimes through much struggle, but I also want to challenge why we don’t put in as much effort to seek out other marginalized voices who, for various reasons, may not achieve the same level of visibility without someone or some space to create the starting platform. I’m with Loma when they say, “REPRESENTATION IS NOT LIBERATION.” I joined Apogee because I’m not interested in having conversations that begin, “Why don’t more poets of color submit to our journal?” or “Do we have enough Asians? Women? Queers?” I want to insist upon the worth of writing that is commonly overlooked because of its aesthetic strangeness or because it speaks to experiences that white editors do not recognize firsthand. And I want to keep celebrating and supporting these writers that publish through Apogee all the way through their writing life.

I want to believe this work is part of a larger creative challenge. To live a poetic life for me means to reach my fingers as gently as possible into the spaces that will allow me in order to learn a more tender touch. I write about people I love and people I lose over and over. This work, as both a poet and editor, means constantly being disappointed as well as being surprised. In my poetry, I tell myself, “Do not reproduce the harm you see in the world. Stop it here.” In my editorial work, I tell myself, “Do not reproduce the harm you see in the world. Stop it here.” In these repeated utterances, I learn to fail remarkably and open myself to learning better each time.

Of course, we can’t pretend that being an editor means we are without subjective aesthetic tastes. There are works we gravitate to over others. What works are you drawn to? What speaks to you on the page and leaping out of it?

J: Muriel, I love this: “Do not reproduce the harm you see in the world. Stop it here.”

I worry I’m not very good at doing that. It makes me really thankful that we function as a team in that we both find struggle and knowledge from remarkable failure. I fear I reproduce the harm. Sometimes, I find myself tearing others apart as I have been torn. Not literally, but the harm that I’ve experienced has transformed me into a cutty bitch and if I eventually self-destruct as a whirlwind of rage, I wasn’t meant for this plane in the first place. It’s not that I’m intentionally harmful, I’m just generally miserable and often find myself most critical of the poetry, poets, anything really, in which I see the clearest reflections of myself.

Envy informs my taste.

Muriel, I’m still figuring out what my taste is but what follows is what I got. I’m most interested in work that constructs and performs signification systems that are alien, hybridized, or dead to me. To interpret novel signs and decipher the context in which those alien signs are written or vocalized, I live for it. To me, this looks like punning, transliteration, code-switching, portmanteaus, slang, mistranslation, polyvocality, pidgin, accent, patois, gibberish, etc… it looks like work that flexes a multilingual tongue to construct signification systems that are new to me, but also, in which I hear echoes of my own hybridity. (Dance Dance Revolution, TwERK, Corpse Whale, A Swarm of Bees in High Court, Mess and Mess and, Hymn for the Black Terrific, Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands / Rebelión es el giro de manos del amante). I think Caroline Bergvall, Cathy Park Hong and LaTasha Nevada Diggs wed soundplay and sound poetics to hybridized signification systems in ways of which I am super envious. I love work that flexes it double-jointed literacy—the code-switch as lil volta—because it gratifies me to see the dominant rhetoric around literacy neutered by that which it cannot contain.

I think of these poets (and several others) as the harbingers of the polycephalic goddess, poets who venture into the liminal space where a preexisting signification system fails. These poets utilize the gift of a split-tongued code-switch to create limitless language futures. This production is political because it encourages those of us at the margin to invent and imagine our own futures, a realm of imagination which we have been denied.

I may denounce the approaches of several white conceptual poets, but that does not mean I haven’t learned from them. I’ve learned from every trauma I’ve experienced, and I would not exchange those experiences for anything—except a mil, maybe several thou… Point is, I’ve learned something from these poets too. My biggest frustration with the “Conceptualist” moment in writing, is the belief that found text can percolate through a subjective gaze and the textual product can somehow reveal an objective truth. That’s how people think of the Bible. The awareness of subject-position (which those of us at the margin know through our lived experiences) was a way to disregard non-white writers producing conceptual work. Is a poem that abides by the rules of an imagined hybrid signification system not conceptual work? What about Robin Coste Lewis’ radical assimilation of found text? Her book exists within a tradition of conceptualism not wrapped in white privilege… so there’s that. She is not an anomaly. These works cannot be tokenized or disregarded as conceptual writing precisely because poets and gatekeepers frantically work still to erase and omit non-white conceptual writers from literary history.

A poet recently came for my neck about me being some sort of “textual purist.” If anything, I’m a cave troll who loves a faulty dichotomy born of contradictions. I just believe that the poet who uses erasure exerts their agency over an original text to transform that text into a subscript or a superscript of itself, so that the writer may contextualize the original as subordinate or superior to the poet’s (re)vision. Scoot to the left so I can center my gaze. To employ erasure is either appropriative or assimilative and that is dependent on a poet’s subject position, the subject position of the original author and the original text itself. When a poet of the margins constructs poetry using found text or erasure, and her result is poetry that illuminates the shortcomings of the pre-existing, dominant rhetoric designed to smudge her out. I see that and say, pop the fuck awf. I see it as a performance of radical assimilation. The act is quite opposite from performing the appropriation of the autopsy of Michael Brown. Although both are “conceptual.”

So I’m into and would love to field more conceptual work through Apogee—I just want to read the conceptual work of woke-folk, who I think get how these techniques can be employed to reveal political truths as they pertain to themselves. You cannot siphon symbols through yourself and call it objectivity. That’s the same idiocy that’s lead several of my fellow citizens to not believe in dinosaurs.

I also love concrete poetry. We published concrete poetry in the last issue! Again, you look at the anthologies (concrete poetics never ever came up in graduate school) and you’d think concrete poetry is cis-white-male (and like, not an American thing). And I’m like side-eye; Thomas Sayers Ellis had a short series of them in Skin, Inc. I think of Basquiat’s work in the language of concrete poetics. And while I question his celestial alignments, I love and learned a lot from reading Christian Bok’s Crystallography.

Basquiat but wait, can I spiral for a minute????

For whatever reason, I’m very critical of ekphrastic poetry. I, like everyone it seems, got into Thrall. But when everyone is getting into a thing, I grow skeptical. And now, I’m tired of these same approaches. So I love Thrall, but I love work that leans in a little too close to Trethaway a lot less. I seek a poem that bewilders me in my ignorance, one that some might consider bad, inaccessible or weird by the standards I was taught to celebrate in graduate school. I prefer a freak lyricism over the poem that exercises the same techniques, same rhetoric, same content as something I’ve seen beautifully done before—you might replicate beauty, but can the poem do anything else? I believe in Horse in the Dark, Vievee Francis writes, Why make something beautiful when I’m not? I feel that.

#teamnotbeautiful

A few years ago, I had a very lit late night conversation with a friend, in which I asked him about his use of pop culture references in his poems. He anecdotally referenced witnessing specific cues embedded in his poems lose their cultural significance, or watching their significance change over time. That stayed with me. I think that when we are celebrated by our editors and mentors for turning to pop-cultural iconography, hip-hop iconography, whatever, we’re being told to date our work. (That is not to say that people do it really well.) But I have a fantasy-futurist streak and it doesn’t excite me all that much as a technique–I’m a hypocrite …this email is littered with obscure-enough references. Roberto Montes posted about this on social media recently. I want to echo his concern. I’m just weary of POC writers being pigeon-holed as producers/commentators of cool culture. The marketing of POC “coolness” reinforces the status quo that we are out here to produce a “cool” culture, a culture that’s dated and to be exploited and monopolized by our white counterparts who just wanna be us. And then we are made invisible and our work is stuck in the past. *sips tea*

I am happy to contradict myself. Michelle Lin’s poem “Portrait of my Mother as Mystique from X-Men” is the only poem that we’ve published that I’ve brought into my own composition classes.

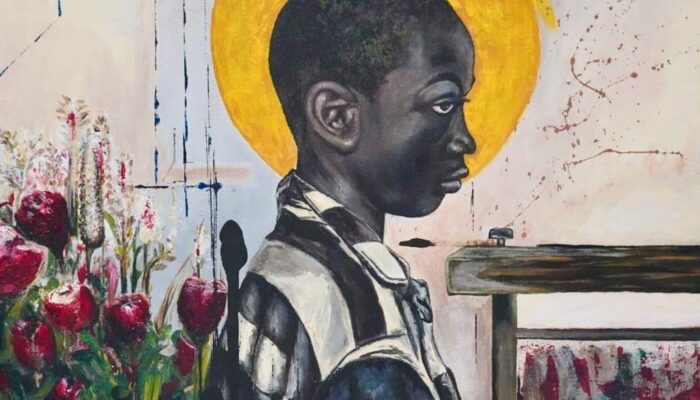

My fave type of ekphrasis:

Otherwise, down with the lyric poem—love a good lipogram. Again, I envy. Writing in closed forms, syllabics, rhyme—I suck at it all. I’m down with writers who bring that duende heat. I think Thylias Moss’ and Spencer Reece’s narrative poems have that slow magic, the poems don’t rush me to where I’m going. The Road to Emmaus was excellent. I love work that performs absurdity, I’m thinking of Mathias Svalina, Heather Christle, and Roberto Montes’ I Don’t Know Do You? I dunno. I’m versatile.

I just wonder… Cathy Park Hong once wrote that some folks poets get rewarded because their work slakes white guilt. I believe this to be true. I’m trying to figure out how… I have a few thoughts…

Anyway.

Here’s a poem I absolutely love of Zubair Ahmed’s from City of Rivers:

I’m drawn to poems in which the speaker mythologizes the self as a necessity of survival.

I am drawn to work that reveals the speaker’s conviction (belief? faith?) as imperative and/or imperiled.

I want to feel both the infinitude and the finality of death in every full stop dot.

*which publishing experiences are the most positive for you? which have been the most negative? Which communities (poet/or not) do you find yourself most comfortable in? and why?

*what would you say to someone who accuses us of commodifying identity?

M:

Yes! I’m so with you, particularly your thoughts on conceptual poetry and how writers of color can disrupt signification systems. I echo your sentiments too about being interested in works that subvert the relationship between signs and meaning, which I think becomes increasingly important when dominant forms of language-making drawing from white supremacy, misogyny, classism, etc. also come with an appraisal system for what constitutes acceptable work that they choose to welcome into its folds. Certainly, writers of color can ascribe to this system without challenging it. But like you, I’m interested in writers who flip the script–Robin Coste Lewis’ debut book being one of them. I also just started Douglas Kearney’s Mess and Mess and, which so brilliantly explores the static between identity politics and the process of art-making. It’s a book that seems to insist upon laying out all the shit that makes up who we are rather than offer up some neat assemblage. I too want that mess.

I still have some apprehensions about conceptual poetry that I’m still trying to work out, which I think has more to do with my own personal induction into that movement and the overwhelming whiteness of that exposure. For example, I love erasures. I teach Mary Ruefle’s “Melody” since it utilizes so many different forms of redaction that it always yields productive conversation in class. But I also think of Solmaz Sharif’s essay, “The Near Transitive Properties of the Political and Poetical: Erasure” in which she troubles the popularity of erasure poetics and how, if not careful, it can become a tool of the state rather than one that tries to challenge it. She writes, “I believe social quests for freedom have much to learn from freedom enacted on the page. And that this conversation should happen on the level of reading and not, as it often is, solely on the level of intention.” I guess this is my way of saying I’m not interested in puns for the sake of being clever, cute or gimmicky. I love the kind of conceptual poetry that realizes that there is more at stake and that upsets the very tools that enact violence upon marginalized people. And I care less about intention these days.

I’m a staunch defender of the lyric. Why is it no longer sexy to say that?! I was with a group of poets once and someone said, “The lyric is dead” and I was like:

I love that the “I” is becoming something other than itself as the world transforms ever so rapidly. I as more singular in some instances than others and other times, so inextricable from the multitude. I love when “I” fall apart. The fragmented lyric. Myung Mi Kim’s poetry as a record of trying to reconcile the violence of war and colonization through these varied utterances. Some place between coherency and incoherency. Metta Sama, in a different way, folding the “I” into itself repeatedly to see its new forms as a way of contending with trauma–the way her lines are constantly pushing against themselves and against traditional ideas of testimonial (what it means “to tell”).

I love too the lyric poem that plays with affect.

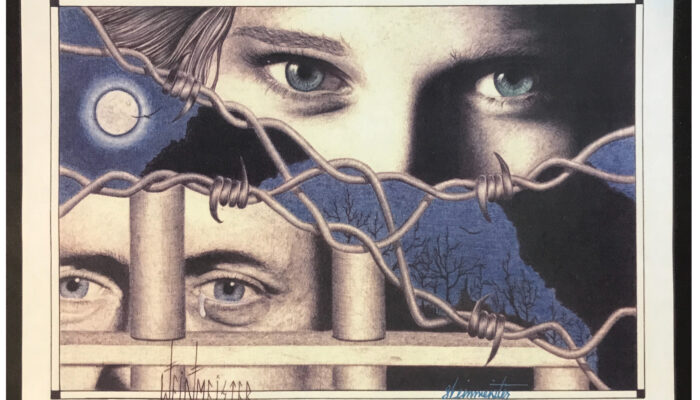

And I love cyborgs and chimeras. Poems that look like Wangechi Mutu‘s mixed media collages:

I love hybrid work too! Work that confounds its readers about genre. Work that draws from botany, topography, and the fine science of nose-blowing. The poem that is also a diagram. The poem that is also the torn seams of a burning flag. A poem written entirely in shadows. A poem that is half girl and half wolf. A poem that is at once the unhappy queer and concordance.

Joey, I’m noticing that you and I share an interest in liminal spaces and celebrating the tensions that exist within them. I think what this means for our readers is that we are interested in work that explores tensions in identity politics and aesthetics, because in our own artistic practice, these are the things that continue to confound and move us.

And I think these are productive tensions. Staying true to those moments of uncertainty and laboring over the answers is what keeps us from the trappings of turning identity into commodity. When you say commodity, I think not only of what can be physically bought and sold but also the intellectual exchange that can potentially instill upon a static presentation of identity that offers up rigid categories of how race, class, gender, sexuality, etc. can function. It’s why I’m wary of literary magazines that have identity-themed issues. For example, Rattle‘s most recent “Feminist” issue that features a crying white woman on the cover seems to reinforce what women of color knew all along, which is that the gatekeepers of feminist ideology are white women and their aestheticized pain means much more than the experiences of women of color. I think that’s the danger of commodifying identity, which is that it forces out other voices on the margins in favor of visibility of the other.

This is not to say that Apogee is not a flawed machine. I think we ask these questions of ourselves at every turn, especially as we grow as an organizational body, welcoming new editors and seeking out alternative sources of funding. We carry the burden of representation with us. What choices can we make to enable us to continue to ask these urgent questions and deploy the right actions that do not reify the systems we seek to destroy? I worry when things seem too easy. Capitalism builds in so many opportunities to exploit and we need to be wary that as publishers we do not become susceptible to these false ideas of scarcity. We need to keep making chasms in the systems that hurt us.

I have my very first short story coming out in Fairy Tale Review and I was so moved by the editors’ thoughtful comments on revisions for the story. One of their comments was about a headless character who utilizes gender neutral pronouns in the beginning and then takes on masculine pronouns when the figure’s identity is revealed towards the end. They wanted to make sure that I wanted that pronoun switch to appear seamless and when I said “Yes,” they asked no further questions. There was no tiresome back-and-forth about lack of clarity for the reader or narrative consistency, but rather a quiet acknowledgement of my queered approach to pronouns and gender presentation. This socially conscious approach to editorial work is one I hope to emulate (and many thanks to Fairy Tale Review for setting such a good example!)

Choice and agency are so important to me when it comes to publishing. Once I realize I am part of something that is more interested in advancing a legacy of whiteness and band-aid change, I revolt. Once I realize someone wants to make an example of me as a queer woman of color to taut a diversity that is not there in a publishing space, I take myself out. My worst experiences in publishing have to do with how people retaliate when they realize the jig is up and that they will have to do a lot more work (that is not mine alone to do) to change the paradigm.

I believe in being strategic by being as precise as possible with my words and performance. Community organizing has taught me how to deal with shit that hurts in creatively strategic ways. The community organizers that I admire are mindful and believe in social change through small movements creating large ripples.

I struggle to find communities where I belong because I see so little of the above happening in academia and in publishing. Perhaps it speaks to the messiness of my needs as a writer, activist, and professional grump. The closest for me is Kundiman, my beloved Asian American literary community, comprised of writers who are educators, academics, organizers, and so many other things across an array of experiences. As a Kundiman fellow, I get to spend three summers with Asian American writers who sit in a circle where we swap stories about our struggles and the sacrifices we make to become writers. Every retreat is like shit talk, write, cry, eat, cry, cry, eat, eat, write, cry, write, listen to Sarah Gambito give precious love advice, and try to avoid looking at Joseph Legaspi’s face because if he starts bawling, you’ll start bawling. The kind of crying that comes with knowing that something so beautiful can only be accessed in small snatches of time. Or maybe I just cry too much. I don’t know.

There’s my Kundiman community and my community of sea crabs.

My hope is that Apogee becomes a community for our contributors. As we move forward, I want us to continuously celebrate our contributors’ successes long after their work appears in our pages. I know it is asking a lot to entrust in a community when the rest of the world is so barbed and cutting, so it means a lot when writers share their work with us! Especially to two outlaw poets just trying to collect their bounty in deep space.

^USx∞

photo: Xeno

Muriel Leung is from Queens, NY. Her writing can be found or is forthcoming in The Collagist, Fairy Tale Review, Ghost Proposal, Jellyfish Magazine, inter|rupture, and others. She is a recipient of a Kundiman fellowship and is a regular contributor to The Blood-Jet Writing Hour poetry podcast. She is also the Poetry Co-Editor for Apogee Journal. Currently, she is completing her MFA in creative writing at Louisiana State University. Her first book Bone Confetti is forthcoming from Noemi Press in October 2016.

photo: Xeno

Seems almost everybody hatesJoey De Jesus but it’s whatever. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Barrow Street, Beloit Poetry Journal, Blunderbuss Magazine, The Cortland Review, Devil’s Lake, Drunken Boat, Guernica, RHINO, Southern Humanities Review and elsewhere~ He is Poetry Co-Editor at Apogee Journal and lives in Brooklyn.