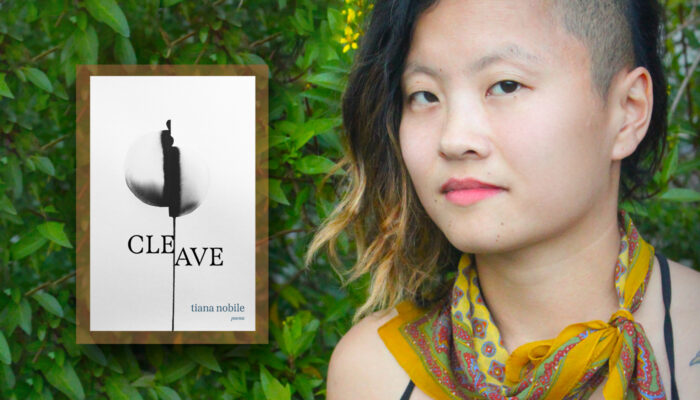

(Pictured above: The author teaching English in Cambodia)

by Victoria Cho

My elementary school classmates ask, “Are you from China?” “Are you from Japan?” I say no to both. They ask, “So where?” I say, “My parents are from Korea.” They ask where that is. I say, “Close to China and Japan.” They don’t ask any more questions.

***

My brother and I are sent to a summer camp for Korean Americans in a small Korean town. The other campers are surprised we don’t speak Korean. The teachers give lessons on Korean music and food. My brother and I are bored and play basketball. When we return to Virginia, my parents ask if we picked up any Korean. We shrug and say, “Not really.”

***

I am a college freshman. I join the Korean American Student Association. We’re planning the first outing of the year, and someone recommends a club. Someone else says, “That place is too white.” I realize the only places I go are full of white people. I realize I’d feel uncomfortable at a place full of Koreans. I drop out of the Association. I make new friends. None of them are Korean American, but a few are not white. It is my first time with not white friends.

***

In Thailand, locals greet me with, “Konichiwa.” I assume my colorful outfits and short haircut reflect Japanese trends. I almost don’t get a job teaching English because the school principals don’t believe I speak English. I tell one principal, “English is the only language I speak.” She asks, “But your face?” I get this question everywhere. Vendors and tuk-tuk drivers ask where I’m from. I say “America,” and they ask, “But your face?” I say my parents are Korean, and they nod with satisfaction.

***

People say “Konichiwa” and “Ni-how” to me on the streets of New York. They are usually non-Asian men and occasionally teenagers or children. My responses range from, “I speak English” to silence to curse words. Sometimes waiters or shop owners in Chinatown or Sunset Park say “Ni-how” when I enter. I speak English, and they switch. The transition is fluid and forgotten.

***

A guy I am dating says I am the third consecutive Asian woman he has dated. I think of the time one man told me Asian women are known for having small, tight vaginas. I think: everyone I have dated has been Caucasian and male.

***

A drunk young man on the subway asks where I’m from. I say, “Virginia.” He asks where my parents are from. This is what people ask when they want to know why you look like you do. I reluctantly say, “Korea.” He asks if I speak Korean. I say no, and he wags his finger at me. I stop speaking to him and look annoyed. He apologizes. I think of my guilt that I do not speak Korean the rest of the ride home.