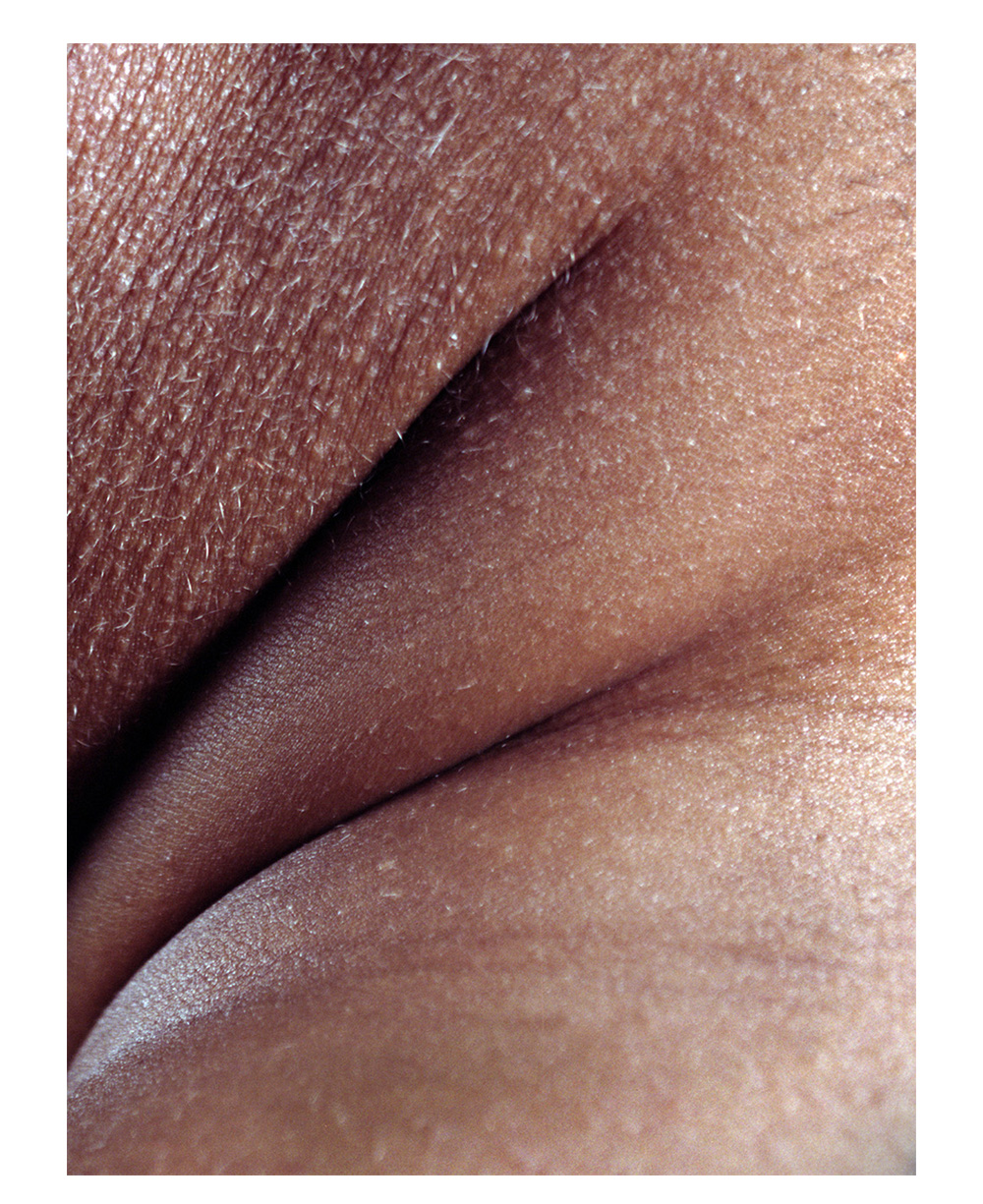

Like All the Red Things We Say to Describe Blood but Blood Itself

Sydney Jin Choi

to my back, flatten my body, take deep swallows to keep blood from leaving me. Funny how the color of blood doesn’t remind me of rust.

Rust is brighter. My uncle, a mechanic, called it cancer for metals. The quiet decay of a machine. They found the rust in his lungs. Scarlet flecks in his handkerchiefs—hybrid carnations in bloom.

Bloom, as in to grow, to open. As in petals peeling away from a center. As in the sun emerging, radiating, the first spray of light that paints the morning.

In Oregon, my uncle rests at home. Thumb rubbing against the knuckles of his missing fingers. I don’t remember how he lost them, but he was born left-handed and learned to adjust. A first-born son, a Chinese man in Portland found

religion. Wine as blood. Sacrifice as blood. Blood like tar, like fresh paint on a fire hydrant, like canned tomatoes on the kitchen floor. My mother says, perhaps, they’ll convert me

at my deathbed. In the morning, blood flows down the back of my throat, taste of metal, rawness of sinuses. I think I hear my mother weeping. Soft hiccups before coffee, scrape of silverware against Teflon, more rust in our breakfast eggs,

scrambled. I leave bed, face streaked with a line of ink. In the bathroom, I succumb to the blood, tilt my head forward and watch it stain the porcelain sink.