Happy Thirtieth Anniversary New Jack City

Xavier John Richardson

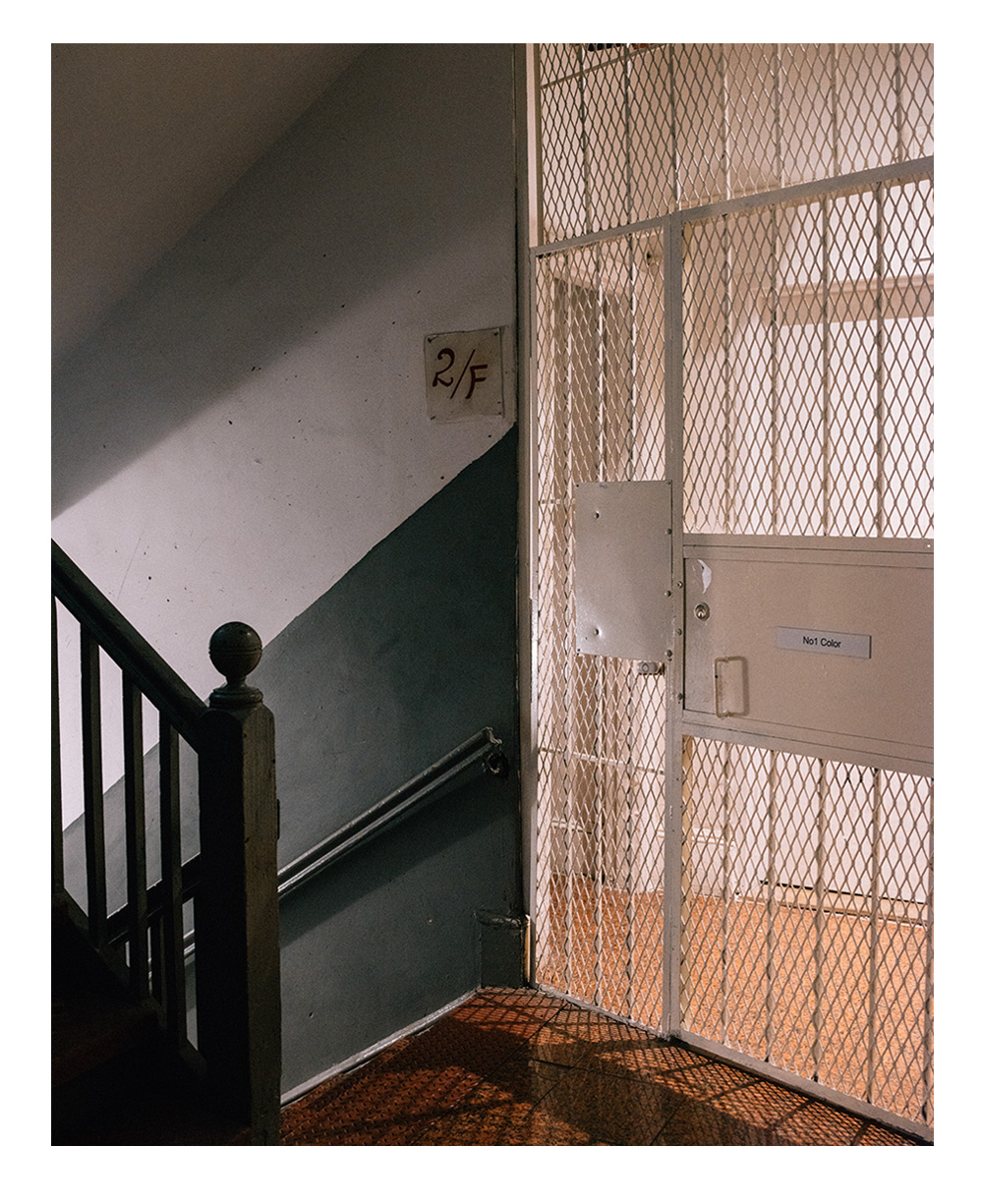

I remember that movie in theaters. I remember the war on drugs that inspired it. Walk with me. It’s June 1, 1991. Me and my boy, Danny Boy, are walking past the GCC Walnut Mall I, II, III, on the UPenn campus, just four blocks from crack vials that litter the sidewalks, drug boys with pagers, their clientele circling, scarves around their heads or matted, dried-out dreads, always circling for someone to beg for money they say to get something to eat. Or want to buy a date? Want to buy these Nintendo cartridges? All three, ten dollars. No, five! Five dollars! This is what the headlines call the “Wild Wild West” of West Philadelphia.

I live three blocks up the street. In the Neutral Zone. Danny Boy is around the corner from me. We pass here every day, coming home from the train we take to our civil service job, typing that data, lifting that phone, like Paul Robeson—whose house is just a few blocks up this same street—singing about a different “Ol’ Man River.” The first of June, with nothing better to do, we buy tickets to see the film New Jack City. Fifteen minutes into the film we’re tossing our popcorn, still hot, and cold sodas rattle the plastic bag in a garbage bin, raising up a sour air. Mostly we’re mad at ourselves. We should’ve known better—Denzel Washington, in Glory, before that Jamaal Wilkes in Cornbread, Earl and Me, Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs in Cooley High, Brock Peters in To Kill a Mockingbird, Jesus in the Bible . . . all are murdered before the end credits role. Besides Spike Lee and Robert Townsend, when is the last time Hollywood came through for us?

Danny Boy is a college graduate, was a SEPTA train conductor. The house, the car, the wife he adored, the dream, he put that in a pipe and smoked it up a few years before I met him. Now, Danny Boy drinks St. Ides malt liquor like it’s coffee. Or methadone. Danny Boy and I have nothing in common except the color of our skin and where we work. I rarely have much in common with friends, other than where we are at the time.

We head up the street to tell our boy, Marvin, don’t waste his money. Chris Rock, the comedian, in a dramatic role as a crackhead turned snitch. That’s hilarious. Ice-T, the anti-cop gangster rapper, has the nerve to be playing a police detective. (I know, since 2000, most people know Ice-T as detective Odafin Tutuola on Law & Order SVU.) Judd Nelson is the obligatory white lead. No other black film could get a Judd Nelson in the 80s. His calendar is more flexible by 1991. Mario Van Peebles, the director, plays the lieutenant who needs “New Jack cops to handle New Jack crime.” Wesley Snipes, the dancer from Michael Jackson’s “Bad” video, plays the over-the-top villain. Wesley Snipes seems to be the only actor not taking himself too seriously. Almost like, if you think this is what a real drug kingpin looks like, Wesley Snipes is going to have some fun. In real life, if your crew is a dozen coldblooded killers, try to punk them like Wesley Snipes’ character did his crew and see if they just sit there around the table, quaking in their boots. Marvin is a former SEPTA bus driver. Failed drug tests did him in. Marvin likes to snort the cocaine he doesn’t step on with baby laxative, mix it with baking soda, add water to boil it hard, break it up into crystals that fit inside little plastic vials sealed with a bright red top. The vials, called “caps,” go 2-for-5 dollars. Each high lasts 10 or 15 minutes. That’s Marvin paying the rent in a lower key New Jack City kind of way. Marvin is a family man. He has adult everyman responsibilities and perhaps a level of maturity that Danny Boy and I haven’t reached.

When we get up the street, there’s a light in his living room, the inside door is open, the stereo loud. Fatima must not be here. We knew the lady of the house would hold us accountable; even if we wanted to, we wouldn’t each other. Marvin and his boy Maurice sit around a hexagonal kitchen table with a glass top. There’s a high school science scale. Marvin would laugh at being compared to Nino Brown. Maurice would have liked it, but he was a wannabe. They’re dividing up caps, smoking Newports and drinking Heineken, heads nodding to a spitfire rap over a phat track.

Danny Boy’s eyes light up like a cartoon character. Let me get one of them jawns?

You want one? Marvin turns the music down, asks me about a beer.

Noises from the back. A brother, Leem, walks out of the hallway, buckling up baggy stonewashed jeans with those question marks inside, inverted Guess triangles all over him: What up, fam? By the time Danny Boy gets back from the kitchen with our beers, a crackhead, not that far gone, walks out of the bedroom with that smokey complexion, those swollen chapped lips, burnt fingertips, and old man rivers running red in her eyes. Marvin asks: You want her? I pass. I already have a beer in my hand. Marvin motions to Maurice. Maurice picks up two crack vials off the table. The crackhead holds out her hand. Maurice lets the vials tumble into it. She closes the caps in her grasp as tight as the hold they have over her. Back toward the bedroom she returns, never looking at Danny Boy. He follows, taking his time.

Maurice gives me that look that insists that I think I’m too good to do what they do. Nobody belongs here. But no matter where you come from, when you’re here, you’re here. There is no there that matters here. You learn that fast. Or you become a history lesson.

There’s a local television personality who comes through. When she needs to get high, how low will she go? Lawyers and politicians. Several pro athletes. Usually, the jocks don’t get out of the car. A tinted window is powered half down, they wait, like they’re god’s gift making a drug run. Marvin swears he knew about Doc Gooden’s habit long before the New York Mets did. Too many cops, firemen, teachers, housewives, civil servants. That tan line around a naked ring finger. No longer earrings, only holes remain as remnants of a past. No longer a lot of things, including shame. They left it in a pawn shop a long time ago.

No matter how many people you’ve seen lose a job, a house, a car, getting up from where they’ve crashed and picking up where they left off without combing their hair, they don’t change clothes or otherwise pay attention to themselves. They start doing things you never thought you would see a human being do, just to get that 2-for-5, put it in a tin soda cap with the liner popped out, a hole punched through to attach it to a piece of hamster bottle glass straw, light a match under it, give suck over an open flame. They’re chasing the ghost of that blast the brain releases that one time, it can be the first time, never the next time. It just has to be this time. But never again. They’ll try again. Because nothing can shake their faith in ghosts. They have the proof. They are becoming one themselves. Knowing all that, having seen it firsthand, you’d think somebody would have to already be high to try crack. Many are already elevated on trees or laced Js the first time they let somebody light up the pipe for them.

Crack doesn’t put anything into you, it brings things out. Brings out the worst in a person. Revealing what you were already capable of. There are some crackheads who will never get on their knees in a water puddle, between an open car door, and let a 12-year-old boy grab their 32-year-old-mother-of-three’s head between his legs, never to look at any woman the same way again. Crackheads who will steal from everybody, never lift a dime from their own mother. Others leave their child in a car with the windows rolled up on a too-hot summer day and get charged with second-degree murder. They follow an old man into his home, pick up a ball-peen hammer off the kitchen counter, beat that old man’s skull to mush for an old transistor radio—another unsolved crime nobody’s trying to solve. Then there is Gary Heidnik, four years ago at 3520 North Marshall Street, riding around in a caddy, kidnapping, torturing, murdering, dismembering, and cooking crack-addicted women. Heidnik’s notoriety inspired The Silence of the Lambs.

Like dogs, guns can smell fear. This time last week, Danny Boy threatened to shoot me with a chrome-plated 357 Magnum he found in a paper bag on an empty SEPTA seat before we met. A month prior to the threat, I had gone with him to get the gun out of a pawnshop at the bottom of Lancaster Avenue. He didn’t want to go into that neighborhood alone, because we both remember the night the Jack of Hearts was stuck up, on Lancaster Ave, right near where the women wait for the 43 to visit their baby’s daddies at Eastern State Penitentiary. The police never came. I don’t even remember the music stopping. As a matter of fact I know it didn’t. Marvin had to shout to me what happened over the Soul Sonic voice sample in Doo Doo Brown.

The threat began when Danny Boy wanted to watch Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls go for the sweep against their arch nemesis, Isiah Thomas and the Detroit Pistons; Game Four of the NBA Eastern Conference Finals, and I have a big screen color TV. All Danny Boy has is an old 12-inch portable I gave him:

You’d die over a basketball game?

If you shoot me, you still won’t be able to stay here and watch it.

I’ll shoot you in the leg then.

How does that improve your situation?

Jump cut to Chris Rock in New Jack City, whining about how crack “is calling me, it’s calling me.” Everybody knows that the only time a crackhead thinks about crack is when he has the money. Withdrawal is for heroin addicts. A crackhead can work all week and not think about crack one time. Then, as soon as that paycheck hits his hand, crack is all he can think about. Until he’s smoked up every last penny. I say “he,” because a woman can always get money. She can always think about more.

Sheeda, the young girl who lives next door, stops by. Probably on her way to a party with some guy who drives a nice car, fires up fat blunts, and isn’t above buying groceries for the house. Sheeda dropped out of school at 15 when she got pregnant with her daughter. She’s a blunt hawk, there are always fat blunts here. Marvin’s generous. He keeps up with what’s where on a given night: Where the party at? Sheeda likes that too. The crackhead comes out of the bedroom looking like Danny Boy wasn’t nice to her. Nobody says anything. She’s out the door. Danny Boy must have heard it close. Here he comes, smiling. Like . . . Danny Boy was never really my friend. I was his.

We met on Danny Boy’s first day on the job. He was living in a boarding house in North Philly, tying his clothes up in a plastic bag and hanging it from a doorknob to keep the mice off them. I introduced him to my landlord, vouched for him to get an apartment, took him to the bank and showed him how to open an account. He had been taking his wages to Chinatown, letting them charge him 1.65% to cash a paycheck, 3.2% for a tax refund. Danny Boy didn’t even own a wallet. He’s 32, four years older than me. He wears denim overalls like that’s cool if you’re not a member of TLC. It didn’t hurt me to help him. I didn’t need a reason. That puzzled him, and maybe fueled distrust. My mother always told me that it was going to throw people that I had that way about me. The moral of the story? When somebody doesn’t have a friend in the world, they will usually show you how come.

But Marvin is cool. And I like Sheeda, with her dolphin inside a bamboo hoop, electroplated, gold earrings, nugget rings and chains, red, white and blue FILAs. All kinds of women come around, even those who don’t get high. Not like those who send love letters to serial killers, but not unlike them either. And to be fair, not just women. After all, I hung out with Marvin too. The rest of them, we tolerate each other mostly because we’re neighbors in the Neutral Zone and Marvin thinks I’m alright. Sheeda’s sister, Ishe, digs me too. But she’s only 17. Ishe’s mother stepped to me one morning when I was out on my front step reading the Sunday Inquirer. Ishe’s mom said, if I want to be friends with Ishe, she doesn’t mind if sometimes I spend the night. I tell Marvin, thinking he’s going to see this as I do.

Marvin asks, if I don’t get with Ishe, do I think that’s going to stop somebody else? At least with me I’ll treat her halfway decent. Some other brother is just going to dog her out. Ishe’s mom is looking out for her daughter the best way she knows how. Herself too.

A brother like you won’t let Ishe go without. Ishe isn’t going to let her mother go without.

Ishe is too young. Let her enjoy her senior year.

What are you talking about? Ishe’s still in ninth grade.

What’s wrong with you? Danny Boy wants me to say something about what I think he’s done with the crackhead, so he can brag about it. Where the rest of us can do things we aren’t necessarily proud of, Danny Boy takes pride in things nobody should. The next time Danny Boy tries to pull a gun on me, one of us is going to use it. He’ll definitely have been drinking. I like my chances. I’ve never felt farther from God. But I like to think that even when I didn’t believe in anything greater than myself, something greater than myself still believed in me.

In At the Movies, Gene Siskel praises New Jack City’s authenticity compared to other black Hollywood movies. Roger Ebert compares its authenticity to the layers of complexity in 1989’s Drugstore Cowboy and finds it wanting. For me, authenticity is something those who weren’t there make up the rules for so they can tell those that experienced it that our truth doesn’t feel real to them.

Danny Boy says he’s headed home to check out Game One of the NBA Finals between Chicago and the LA Lakers: Jordan versus Magic Johnson, baby. Marvin asks me to take a run with him and Maurice. In the car he tells me, There isn’t a $20 bill in Philadelphia— no matter if it’s in the mayor’s wallet, or hidden in the widow’s picture frame behind a smiling grandchild—not a single $20 bill in the whole city, that doesn’t have traces of cocaine embedded in it. Nobody will claim that every single $20 bill in the city has passed through the hands of somebody lighting up a crack pipe in the inner city. The crack trade deals mostly in fives and ones.

Powder cocaine is where the big money lies. Nobody in the inner city, except drug dealers, can afford powder cocaine. Powder cocaine produces the suitcases full of Benjamins in movies like New Jack City. In real life, those Benjamins have to come through a bank, the financing system, through financiers. Some of them cokeheads themselves.

If there was a war on illegal profits from the drug trade, there would not need to be a war on small-time users. There may not be all of the new construction downtown either. An investment in cocaine promises returns that make a mockery of the stock market, tax free, with none of the volatility. More than one respected economist is blaming the commodification of cocaine for stock market losses deepening the recession that caused George Bush to break his promise: “Read my lips. No new taxes.” And yet the Brady Bunch Belt thinks it’s just a “those people’s” problem.

People like Marvin are subject to the volatility in cocaine futures. People like Marvin and the neighborhoods where they do business. In his way, Marvin is just like the front men at after hours spots like The Jack of Hearts, The Watusi, Top Shelf, Brass Rail . . . Those guys throw their weight around like they’re New Jack City’s Nino Brown running things, but like Marvin, they show their books to someone a lot paler and higher up the food chain who takes the lion’s share.

Marvin himself tells me all of this, because unlike the others, I wasn’t born in the city, taking for granted how cash rules everything around me. The system works you. You work the system. That’s how it goes. Everywhere.

I lay out how creating a maze of shell corporations can take care of Marvin’s family if the law should ever come for his assets. Marvin turns to Maurice. I see Maurice smile for the first time since we’ve known each other. A limousine passes, speeding in the opposite direction. On the next block there’s a white stucco crack house, at least five stories, that was never cut up into apartments. No doubt that’s where the limo is coming from. This dude called Clutch, eating a soft pretzel out of wax paper with too much mustard, waves us down. Did you see the limo? He asks, offering the pretzel at us, the scent getting into our ride. That was David Ruffin. “My Girl,” The Temptations: David Ruffin. Dude looked pretty bad. He’s not going to make it.

Yeah, we saw it. Maurice says. Let me get a bite of that pretzel.

The moral of New Jack City should have been, no matter how many Nino Browns are taken down, others will take their place until we take seriously who profits from their rise. What measures can we take to hold those behind the scenes accountable? Not with a war on drug users needing to escape the hopelessness of everyday life.

If we may concede that in order to become a Nino Brown you have to have one of the most brilliant criminal minds of your generation, where would we rank our own minds, criminal or otherwise, within our generation? What might a Nino Brown have become that we can’t? Could a Nino Brown have been instrumental in halting a viral outbreak? Make the production of energy more cost efficient and environmentally friendly? He was definitely a leader capable of uniting people against tremendous and dangerous odds toward a common goal. Our politicians promise these things.

Marvin pulls up in front of Papa Docs, where the drinks are poured generously and it’s almost as dark inside as it is outdoors. Once inside, settled in a booth, Marvin says the Jamaicans told him Danny Boy is hitting the pipe again. I pick up my Long Island Iced Tea. Too sweet. The Jamaicans have a reputation for inviting brothers to the island, never to be heard from again. Their passports show up, back in The States, being used by a Jamaican, because to US Customs we all look alike. Danny Boy had sold them his gat for caps.

Danny Boy told us what you said when he pointed that big Mother Sacoche at you.

I didn’t lie, Rece, I don’t know what else to tell you.

We laugh like only those who know what it feels like when Azreal has pressed her lips to your ear, and as her fingers chill your face, she apologizes and moves away. She thought you were someone else.

Happy thirtieth, New Jack City.