Letter from the Editor

Reader,

“From a small cell, I witnessed the country being brought to a standstill. Like a slow-moving train wreck, the COVID-19 virus spread, infections and deaths increased daily . . . Once inside the walls of San Quentin, the virus ravaged the population. In overcrowded prisons, social distancing is impossible. Every day, alarms repeatedly sounded off as COVID-19 swept through the prison. Not all of us here have been sentenced to death, but the virus changed that. More than two-thirds of the population, including myself, became infected. Fear, anger, uncertainty and a sense of abandonment hung in the air like a fog. I lost a friend to this virus, while some people beyond the walls bemoaned the restrictions and guidelines meant to keep them safe.”

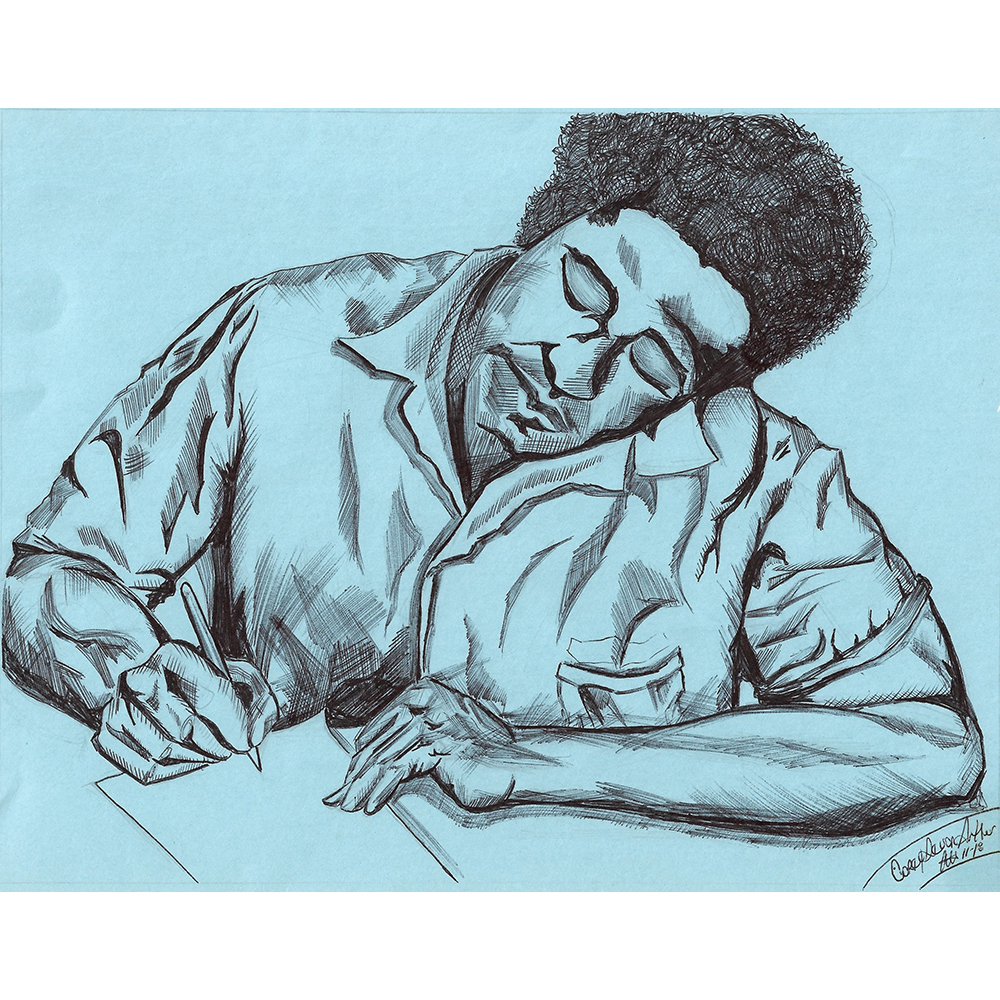

This excerpt accompanies the cover art “Deliberate Indifference” by Rev. M. Seishin Cádiz. It highlights both the ties that bind us—on the outside and inside of prison walls—as well as the enormous gulf between us. While COVID-19 reminds us of the interconnectedness of all humans in society, it also highlights the chasms between the free and unfree. This special issue of Apogee: Inside Out aims to amplify the voices of those most silenced in society, at a time when communication across these chasms has been made even more fraught. Regular COVID lockdowns that include restricted phone calls, visits, and mail delivery exacerbate the restrictions regularly wrought by an exploitative prison telecom industry. We aim to honor our commitment to writers at the margins of visibility by platforming incarcerated voices who have been redacted from the public.

The writers and artists in these pages verbalize the everyday deprivation of life inside U.S. prisons. Loneliness, worry, and longing fill these pages. In Traci Jackson’s “Happy Valentine To Me,” Jackson pleads for love and unity for those who “don’t have the privilege of being with the ones they love.” Jesse Ayers’s poem “Worry & Doubt” depicts a lover anxious about the fate of their relationship while they are locked up, whose worries crescendo with the worst possible outcome: “I worry that you and our baby won’t make it/I doubt I would be able to take it.” The heartbreak of being separated from children especially emanates from these pages, as in April Harris’s “How Long has it Been?”: “It has been twenty four years since I’ve heard the sound of my kids’ chatter./It has been twenty four years of them thinking that they do not matter.” When Chana L. Woods writes “Still you’re my child… life… my/First love,” we witness the pain of this separation. These writers remind us of the reverberations of incarceration—entire families and communities scarred by the absence of partners, parents, and children.

And as these writers show us, the absences are not incidental or solely the result of decisions made by those serving time. They are more often than not engineered by a society steeped in racial and economic injustice. Demetrius “Meech” A. Buckley writes in “Apology Hour with the Sweet Hotel” “. . . the schools in your neighborhood/are not for my children—/if I could remember/what they looked like.” Buckley names a cruel, ironic feedback loop: serial divestment from the education of Black people ultimately finances the prison-industrial complex and the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

While some writers lament the relationships damaged by their absence, others zoom into the horrors of quotidian life. Poet Jason S. Harmon writes:

Drifting…

Further …

Further …

Into this dystopian storm,

Raining rifle-rounds, razors, and rusty bolts.

Indeed, we see this drift into dystopian reality vividly depicted in the moment of waiting for a strip search in Olethus Hill Jr.’s “Laugh to Keep from Crying.” The terrifying anticipation for this dehumanizing event does not dull with routine: “My body went into autopilot as my mind instinctively prepared for what was to come. Feelings of dread, humiliation and degradation immediately invaded . . . I was more concerned with the looming naked dance recital I still had to perform. Ninety-five percent of the time, strip searches are conducted because there’s a suspicion of drugs or other contraband—the other five percent is out of spite.” While Hill Jr. and a fellow incarcerated person attempt to poke fun at the situation to quell their own dread, the C.O. uses it as an opportunity to reassert authority and power. Adamu Chan’s “Outside/Inside Power’’ similarly highlights the way power imbalances distort behavior and social dynamics, this time in the context of white women volunteering in prisons. He beautifully explains, “Prison is a space where, because boundaries and relationships are so clearly defined, and resources so scarce, and because the threat of violence is ever-present, the spectre of power is clear in every movement, every interaction, every breath.” This leads to a reflection on the nature and meaning of safety: “Why do some of us have to live in a world of police and prisons and surveillance, while others live in the normative safety of whiteness, of maleness, or of hetero-ness? The safety and visibility outside people experience here is at all times established by the gun towers circumscribing the grounds of this institution, the presence of guards, of handcuffs, of batons, and the merciless shadow of the parole board.”

Along with the fraught dynamics of strip searches and volunteer visits, these writers bring to light the extremities of deprivation. In Demetrius A. “Meech” Buckley’s story “Juxtaposition,” the narrator admires Sensei, a man in solitary confinement who receives forty-five minutes of outside time (in a cage) a day, who is “in good shape, 68 years old, an undefeated foe against the Michigan Department of Corrections.” Soon, we learn about Sensei’s past along with the narrator during one of their workouts in the yard. The narrator admires Sensei’s will to survive in this environment. Buckley writes in chilling detail: “Losing yourself in an off-corner, square room is hysterical, but Sensei stayed strong for so long where men break like the icicles hanging from gutters, to the point of crashing suicide. The hole is built for suicide. The loop, the mind; the rope, sleep.”

Other writers focus on being deprived of nature. In A. Raheem Ballard’s poignant essay, “When Feeding the Birds is a Crime,” his experience navigating a potential disciplinary infraction for feeding birds trapped inside the upper tiers of the prison is contextualized by fraught engagement with nature outside of prison that involved law enforcement. He remembers “being shot at with salt pellets by park rangers for strolling through a wooded area near [his] house.” He reflects, “In Coconut Grove, the area of Miami where I lived, playing on the Atlantic coastline often meant being picked up by police. The beach areas were marked ‘PRIVATE PROPERTY.’” In his youth, he concludes that “nature was private and exclusive—that it belonged to those with wealth,” only to rediscover a passion for nature in prison, when his connection to it is most limited.

And the deprivations of life inside prison only become more overwhelming when COVID-19 hits. We are made aware of the extreme confinement in which incarcerated people live in Ivan Skrblinski’s “Zelda Metzger”:

The cells are windowless—smaller than your average Walmart parking space. The housing units are stacked five tiers high with the outer windows welded shut. There’s no ventilation. Two small doors, in the front and back of the housing units, are pathways to the tiny cells . . . Each cell has two incarcerated people crowded inside and is cramped so tight, there’s not enough room for two cellies to stand on the cell floor at the same time . . . Armed guards staff the prison. They stand in towers with orders to “shoot to kill” any convict trying to scale its walls.

This confinement contextualizes the horrific outbreaks of COVID-19 inside prisons. Skrblinski describes a bus transfer that resulted in a devastating outbreak, showing with syncopated rhythm the relentlessness with which the virus was passed: “Two days later, the old man coughed. The next day, the old man got a fever. The next day, the old man couldn’t breathe. The next day, the old man died. Two days later, his cellie coughed. The next day, his cellie got a fever. The next day, his cellie couldn’t breathe. The next day, his cellie died.”

The visual art in the issue illuminates what it felt like to be incarcerated during the early outbreak of COVID-19. Both the cover art for this issue, as well as Orlando Smith’s graphic stories, serve as dispatches from the most regulated and confined places in society. And not only do the writers and artists in this issue depict friends and community members infected and killed by the virus—many of the writers describe being infected themselves. In a heartbreaking litany, “Colored, Chained, and with Covid,” April Harris writes, “Strike one: I’m Black, I am a woman of color/Strike two: I’m chained … considered only a number/Strike three: I’m infected, Covid took me under . . .Thirty two days I spent in the dungeon of isolation/With a cough, some chills and a lot of perspiration.”

But as much as these writers reveal about living inside prisons with apocalyptic conditions, they also reflect back concerns about the world at large and the societal inequities that shape, perpetuate, and contextualize mass incarceration. Contributors express frustration and sadness over watching more instances of police murder of Black people, in particular the murder of George Floyd and the uprising for racial justice it inspired. In Rahsaan “New York” Thomas’s short story, he imagines a dialogue between a Black grandmother and grandson during the 2020 uprising, debating the uses and limits of protests. While the grandson plans a big rally at the state capitol, the grandmother, involved in struggles for justice across decades, warns him against it, anticipating loss. An argument ensues over notions of reform.

COVID-19 has laid bare the deep inequities that shape our society and yet, ironically, has also shown us how quickly the world can change. Recuperating a livable present from the forces of obliteration requires us to imagine and work towards alternative modes of living, of being in true community. Reading this work attunes us to the carceral society around us: from police checkpoints at subway stations to the “school safety officers” that police our youth. Towards the necessary path of liberation, we offer the writing and art of those whose freedoms have been erased. Uplifting these voices is one step towards reimagining and remaking our world from the inside out.

Alexandra Watson, on behalf of the Inside Out team and Apogee Journal

“Approximately 25,000 years ago, my people painted their culture on the cave walls in the dark. In contemporary times I draw my culture in cells, often in the dark. George L. Jackson, a hero of mine, also wrote the pains and hopes of his people in a prison cell. He was murdered in San Quentin Prison in 1971, but not before perfecting his revolution that showed humanity he died with ‘Blood In His Eye.’”