Letter from the Editor

Dear Reader,

I’ve been thinking a lot about portraiture lately. More specifically, I’ve been thinking about the records left behind by taking or making a portrait—the way observing can be a mark of violence or love, and the small spaces between the two. Debates around art in the face of rampant white supremacy frequently become simplified to a simple metric of inclusion—what marginalized and minoritized voices are let in this time?—but the language of inclusion, of course, covers up often more insidious violences. What happens to previously excluded bodies once they are let in? In photographs, which have their own fraught history, we can construct a metric more transparent, more bare in its assumptions about the consumption of art: pictures (or any other kind of art) can be captured, but they can also be preserved. What does it mean to take the care of preservation while avoiding the bilious history of capture? Is it even possible to preserve the love but not the hurt? How, in the art that we make and consume, do we trouble those lines, perhaps even unconsciously?

The visual art and writing in this special issue of Apogee are concerned with the complexities of portraiture, of negotiating capture and preservation, in the face of often overwhelming political violence. Yet, as always, there is room for joy and exhilaration, a quiet kind of care that gains force in the assembly of the pieces together. We see this in the visual art; the defiance, poise, and elegance of Zinzi Minott’s “Portal” comes to mind, as does the black and white grace and loaded stare of Daniel Diasgranados’ “bike szn, I.”

We also see it in the writing, with the mix of abandon and loss in Thomas Renjilian’s short story “F** Scale,” charting a series of increasingly explicit m4m interactions: “What’s a guest,” Renjilian asks, “but a good time to disassociate?” Or, as Cyrée Jarelle Johnson puts it in “a machine of mahogany and bronze,” an excerpt from their brilliant book Slingshot:

Atlantic be damned. Sluice your volume

through every of our new-broken windows pierce

as we do—with sin, with everyday, with a wholeness.

There are a number of ways to hold space, to sluice, and Johnson’s work holds that ambiguity—calling to mind the Black Atlantic but also a way to encounter both “sin” and “wholeness” at the same time. Perhaps that twoness is another way to approach the art and writing in this issue. Certainly, the poetry here is engaged with holding space in the middle of transgression and discomfort, whether that be the “3,700 seed capsules… regurgitate[d] to mush” in Angela Penaredondo’s “thedeadteachtheliving,” or the disquieting rape joke told by a drunken uncle in Nik Buhler’s “Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before,” or in Shay Alexi’s omission of acts of sexual violence “[redacted] [redacted]” that renders them all the more present.

In his nonfiction piece “The Good Hair,” Marcus Clayton also marks loss and presence at the same time, describing the freedom in punk music much as he declaims the anti-Blackness at its core; white people in the 90s, he says, “know Vanilla Ice better than… Radio Raheem.” Zoë Eddy describes the witnessing of being indigenous but white-passing in “The Exhibit,” delving into the specific anti-indigeneity that bubbles up in museums. “Oppressive like fog… like sadness,” she writes, of her “Living Red Man” partner’s reaction to these exhibits and the audiences of white curators therein.

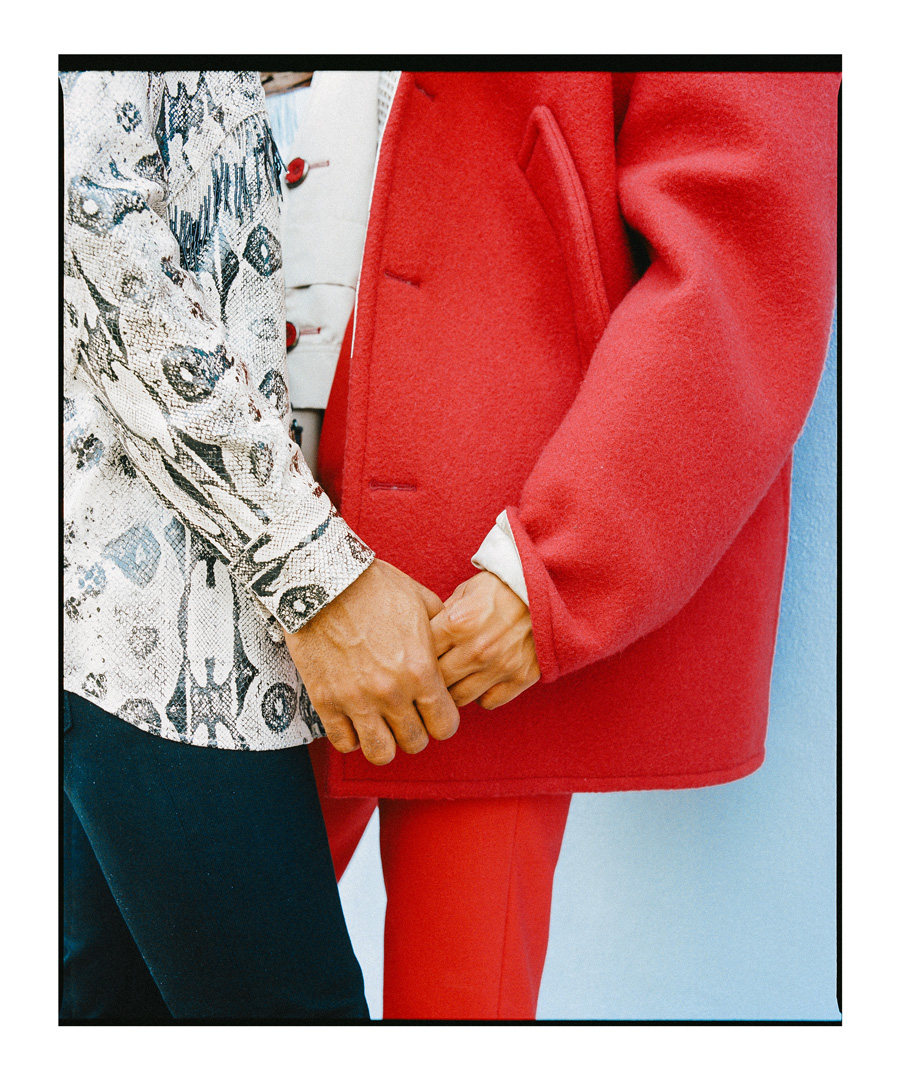

This issue is concerned, as Apogee often is, with mourning loss without centering the violence that causes it. Andre Bradley’s photo pieces, “Bad Selection” from a larger series of images of Black men and boys against a sky-blue backdrop, features faces rendered illegible and blued-out by what appears to be an algorithmic selection process. This work carries loss and anti-Black violence while eliding enacting violence, hinting at the ways in which digitality can erase the Black body. “this is not art/this is bleach/against skin” Ayesha Raees writes in “Bird Flight,” likewise attacking possession of land and legacies of colonialism.

I’d like to end by addressing what’s new, besides the work; firstly, we’re increasing access to our digital issues, proving select pieces from past issues to non-subscribers. Also, in a development I’m especially excited about, we’ve been working with our visual poets to devise alt-text that describes their work in a way that is accessible to blind and vision-impaired readers.

Ava Hoffman’s “1 poem from that I want” is the first piece we’ll publish with this alt-text supplement, and I’m so excited that her work is issuing this forward; it engages in a series of erasures and rewritings of her name, asserting (trans)femme brilliance and rejecting—but still rendering visible—the violence of deadnaming, patriarchal systems of control, and state surveillance of transness. I hope this poem continues a larger conversation around accessibility (and trans legibility) in publishing.

This issue holds many things within it, but I’d like to finally return to photographs as a model for engaging with this work. Look through the pieces. Take them in. This issue, like every one of Apogee, is a breathing, dynamic, thing: it holds space, and I want you to do the same for it. (Take a picture, the saying goes, it will last longer.) I leave you with a wish. May every epidermis facing violence against it, represented this issue and beyond, endure. May the care that we enact in our portraits always outlast the work of the capture.

With love and resistance,

Zefyr Lisowski

Poetry Co-Editor

December 2019