Biology Class

Venita Blackburn

We didn’t even know Ms. Lancaster owned all those animals until somebody broke into her house and got pics: cages lined with shit, torn-out fur and blood everywhere, all over the floors, inches thick, so you couldn’t walk in it without making a sucking sound every time you lifted a foot. She just abandoned them all. So sad. On the first day of school, we walked into class and could hear something scratching and could smell something disgusting. Eventually, we got used to it, the raw, acidic stink of formaldehyde and animal flesh. Turns out the scratching was a bird in a cage in Ms. Lancaster’s office adjacent to the class. We all sat a few rows from the front of the class like always—Vanessa included. When we saw Ms. Lancaster for the first time, everybody got a little wet and hard for the new teacher who wasn’t a total hag. She wore an ankle-length flower print dress over her flat chest and had this soft country attitude that made her seem like a baby, a really smart baby who knew about war and sex and taxes. Ms. Lancaster was tall—thin, sure, but not fit—skinny fat, with carpal tunnel in both hands; her arm meat swung every time she wrote fast on the board or sneezed uncontrollably. She always wrote fast, even with the braces on her wrists, impossible-to-read handwriting with even more impossible-to-understand sketches of body parts, but we didn’t care. This wasn’t the kind of school for caring or trying or being special. Standing out was never an objective. No one was popular. Ms. Lancaster didn’t get it.

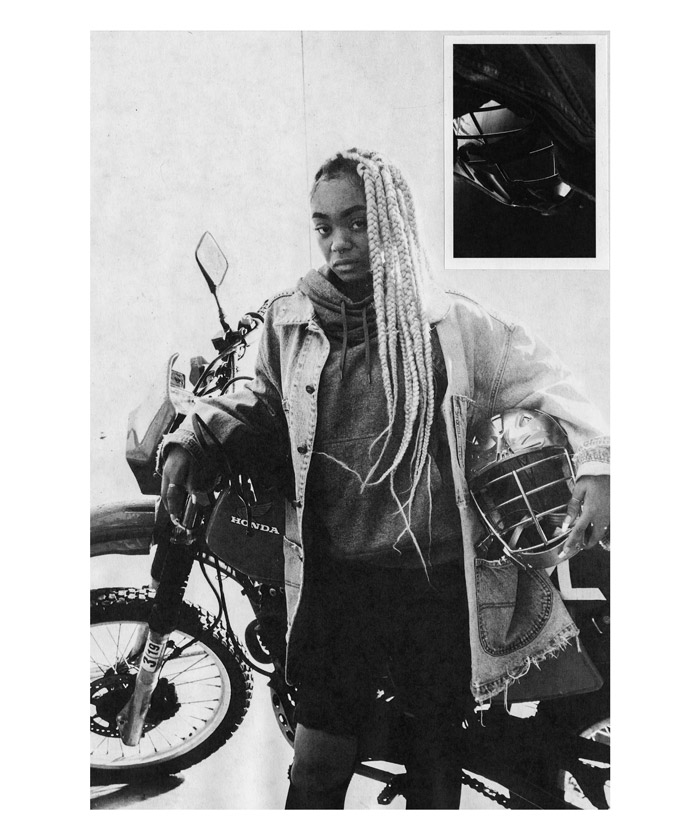

Instead, she learned our names, especially Vanessa’s. Vanessa wore jean skirts and Chuck Taylors with velvet track suit jackets that clung to her shoulders. She ran cross-country so always had some well-defined muscles or shoulder blades pushed back like she might sprout wings. Vanessa lived on the edge of being special but knew (or almost did) how far to go. We had to draw epidermal layers as part of a homework assignment once. Ms. Lancaster demonstrated on the board what looked like lasagna or cartoon ocean waves, then pulled out Vanessa’s homework and called her up to the board, put a long stick of chalk in her hand, and asked her to draw the epidermis. She did, every layer vivid and distinct: the stratum corneum, lucidum, granulosum, spinosum, and basale, each with a specific shape and discernible texture.

“Looks like we have an artist among us,” Ms. Lancaster said.

Things got a little quiet. Vanessa’s lip twitched to hold back a smile. On the way back to her seat, she had to dodge Q, who tried to touch her bare calf. We could tell she felt the change in the room, brought on by Ms. Lancaster’s recognition. We all did.

Q always touched girls on the back of their necks when teachers weren’t looking. He might blow on a girl’s ear until she stood up or made some kind of irritated sound. The teachers always blamed the girls because everything else in the room was still. We never said anything. He never really hurt anyone, so… Only big dudes ever sat in front of Q but mostly no one at all until Ms. Lancaster’s chart day. That was just a little ways away though.

After that skin lesson, Ms. Lancaster introduced us to an ongoing project that she would stretch out over the year. Truthfully, we could’ve done the thing in a week, but even with all that time, half of us turned in nothing at all. There were other, more interesting things to occupy our energies than animal scraps. She had wanted us to acquire a real femur that we would examine, color-code, label, and eventually display. “It could be pig or beef,” she said. First step was to go to a butcher and just ask because they usually throw out the bones after they remove the sellable flesh.

“Ask the butcher to cut it in half, the long way,” she said. “You want to see the marrow, the layers, and the artery that feeds blood to the center of the bone.”

Ms. Lancaster and Vanessa were still getting along then, getting along very, very well, in fact. Vanessa stopped hanging out with us during lunch and spent her free time in the biology lab. Sometimes we glimpsed her in there, petting that bird with a head so blue it looked like an accident, while Ms. Lancaster sorted materials in the classroom; reading at a desk while Ms. Lancaster shuffled papers; or typing as Ms. Lancaster leaned over her shoulder, dictating passages to Vanessa, probably because the carpal tunnel was being a bitch. They seemed to be getting closer and closer over the weeks, because that’s when the photo showed up.

It was a blurry pic of a familiar scene: Ms. Lancaster at her computer, Vanessa leaning over the desk, both peering at the monitor, all of it seen through the bio lab window. The only difference between our memories and the photo is somebody did a half-assed editing job and moved Ms. Lancaster’s hand from the keyboard to Vanessa’s thighs, right under the hem of her skirt. The pic and the joke were pretty shitty but well understood. Vanessa even laughed because she had to, she knew that was the right thing to do; when acid is on the ground, it is best not to fall, best to be patient, step lightly.

Ms. Lancaster of course fell, and the mess was incredible. We saw Vanessa try to go into the bio lab after the photo had circulated, but the door was locked. She knocked and knocked and said Ms. Lancaster’s name, but there was no response.

Boil the Bone

A day or so after that came the seating chart. It was elaborate and color-coded and confusing for almost all of us except for the few who sat down in their appropriate locations without blinking. After some high-anxiety moments of panic, most of us found ourselves in the same places we had always been. In our relief, backpacks hit the ground and feet eventually stopped scuffling around for a home, but in that calm Vanessa still stood. She stared at Ms. Lancaster blank-faced and hard for a long time, long enough for all of us to notice and wonder and look at Ms. Lancaster, all of us waiting for an explanation. It was quiet. We could hear the parrot in the office fluttering against its cage like a plastic bag in the wind. Ms. Lancaster never looked back at Vanessa or the class, just shuffled papers, waiting. Then Vanessa turned, walked, and sat down right in front of Q.

“Oh shit,” a girl said.

Then it was quiet again. Q already had both legs spread wide and stretched out so far in front of him, Vanessa had to step over his left foot just to get herself seated. He leaned over and took deep, obvious breaths. We thought for sure Vanessa would protest. There were empty seats around her, from some students who never came to class—she could’ve had any of those. She didn’t. Instead, she took off her jacket. That got Ms. Lancaster’s attention. Ms. Lancaster dared look incredulous as if she weren’t culpable, then peered around at us as if we could make this classroom safe again. She didn’t understand. We had nothing to give, no reprieve to offer. We were in rapt attention; her performance stunned, captivated. We pleaded in silence for more, more revenge, more mistakes, more shame, more of her to shake loose before our eyes. We looked at her and she back at us with equal expectation, as if all of us could feel Q’s meaty breath on our necks; we held our breath for what was to come. She gave us a lung, a raggedy sketch of a lung on the chalkboard to gaze at. We counted the bronchi over and over, traced their branches until the clock ran out.

Around Halloween we were supposed to be at the next stage of our big project. Find a pot large enough for our femurs and boil them for a few hours until the heat rendered off all the fat and flesh.

More pictures emerged, Vanessa absent from them all but Ms. Lancaster on full display. An entire account formed online: Biology 101-lolol. The first bunch of photos were all in Ms. Lancaster’s office at lunch. She was in all varieties of lonely poses with crudely photoshopped birds in unsavory conditions. There was a bowl full of cartoon cardinals posed like fruit, one bird in Ms. Lancaster’s hand as if she were taking a bite. The birds were always in jeopardy: burned in an experiment, chopped up, eaten, and eventually, used for sexual purposes. The account lost some attention for its incredible claims but regained steam around the time Vanessa slapped Q on the field.

Or tried to. Q always followed her around, doing his creepy guy routine, which was harmless to us generally, so the whole bio classroom’s attention must’ve confused him. Vanessa was bare-shouldered and immovable during bio, no matter what he did, even when he stroked the eraser-end of a pencil down her neck. She never faltered, but outside of that room, Vanessa avoided him like everyone else. Still, one afternoon Q stood right in front of her before track practice and blocked Vanessa’s passage to the field, and that’s where he reached to touch her abs. She swung on him, but he caught her wrist and laughed. Then he just walked away.

Ms. Lancaster was not doing so well either. Her carpal tunnel advanced, and she gave up writing on the board at all. We mostly watched videos in class and did worksheets, or not, while she sipped water and kept her eyes on her personal monitor. That’s when someone kidnapped her parrot.

Paint the Bone

After the theft of her office parrot, Ms. Lancaster’s physical deterioration proved more pronounced than expected. She posted fliers with a photo of her missing pet, her personal phone number in detachable strips. It had a name: Elizabeth. Seeing adults in physical or emotional despair always left us unsettled, except when they seemed somehow deserving, fit into the range of they-brought-it-on-themselves like all the stories they tell us to justify homelessness.

We questioned those stories when Ms. Lancaster fell apart. She came to class with a shoulder brace as if the carpal tunnel had spread like a virus up her ligaments and through her entire nervous system. After the brace came the bloody bandage around her ankle and the limp. It was as if she were losing fights everyday of her life to some invisible opponent, agile and unrelenting. She still sported the floral print dresses, but they hung awkwardly and were improperly buttoned. For one class the band of her oatmeal-colored bra showed just under her left arm, contrasting with her pink and black dress. It was all alarming but somehow wonderful. There seemed to be switches on these people, these adults, switches that could be flicked and their circuits thrown into always-escalating, ever-delightful chaos.

One of the final stages for our major bone project involved some artistic flare. After boiling the fat off the femur, Ms. Lancaster recommended leaving the bone in the sun for bleaching “to make the cleanest canvas.” For many of us, that resulted in an ant fiasco because the bone had not been thoroughly boiled. That, or family dogs literally ate our homework. Those were good enough reasons as any to abandon the whole ordeal and any hope for a passing grade. Still, it worked out for some, and our sun-bleached bones were made smooth, hollowed, a fine canvas. There were a dozen sections to identify and to color differently. After the painting came the gloss, a spray-painted finishing to preserve the work. In theory we imagined a kind of menagerie would form when we brought our final products to class, something bright and celebratory of all the weird effort we’d put into understanding this particular part of the body. In the end, it was not that.

We figured something had happened to Vanessa after winter break. She stopped coming to the bio lab altogether, stopped going to track practice. She had been slowing down for a long time, so no one was that excited about her for the upcoming season, but no one anticipated her complete absence. She’d already been putting on a little weight, but it really showed in the spring. The usual suspect had been thoroughly ruled out: she wasn’t pregnant or anything that absolute. She just kept putting on pounds, her muscles gone and atrophying under the swelling fat cells. Q had already moved on to other interests, wasn’t stalking her in the halls anymore. No one said anything to her about it. We got it. The things girls do to stay safe have to be inventive, manageable, a kind of force field. Vanessa’s sacrifice of her symmetry did not go unrewarded.

The Biology 101-lolol account doxed Ms. Lancaster, doxed her hard. Home address, social security number, SAT scores, online dating profile, all public and all less than amazing. She was as clean as she was country, except for one thing: her animals. She had a hell of a lot of them. The thing that got the most attention was the video of her walking through her living room and tripping over an open cage door. There were walls and walls of tanks with gerbils and ferrets and chameleons but no fish. There were rabbit cages and cat crates and who knows what other kinds of creatures. The abundance freaked people out, freaked out people we never even knew existed. The comments were as cruel as they were creative. Strangers threatened to murder her if she didn’t clean up her house and put the animals in shelters. They accused her of running a puppy mill, then called for her rape and strangulation and even sent around pics of her sleeping, sleeping in her actual bed in her actual pajamas, but with a twist: blood and bruises superimposed on her body.

Name the Bone

No one expected the outside attention or knew how to turn it off or even considered turning it off at all. We figured Vanessa wasn’t responsible. But something was overtaking her. We saw it all happen. She would sit in class, staring straight ahead, never acknowledging a question, her homework assignments poorly shaded or nearly blank. Once, a white board marker clumsily fell from Ms. Lancaster’s crippled hands and rolled to Vanessa’s shoes. The clatter of the plastic on the tile thrilled us. Vanessa didn’t even twitch. Ms. Lancaster was forced to walk to Vanessa, kneel down and reach almost under the desk. We nearly fainted as Ms. Lancaster raised her eyes to Vanessa in supplication. Nothing. Not even a blink and a sigh.

There is something deeply satisfying about watching lovely things explode. Maybe it is about power and longing, but mostly it is about suffering. Beauty inevitably becomes unbearable. That is why we pinch baby cheeks, bite into tiny cakes painstakingly made, why we pay to watch people drive expensive cars off cliffs and fire bullets into young hearts. We need to remember that we are in pain together. Still, there is something to be said about being the teeth and not the bread. Vanessa figured it out like the rest of us. Try not to stand out for too long, no matter who tempts you into the spotlight. It was a hard lesson, but she understood after a few small mistakes.

There was that one time before Vanessa stopped showing up for good. Ms. Lancaster grabbed her arm in the hall right in front of everyone. They hadn’t spoken for months, as far as we knew. Ms. Lancaster looked like hell and a half. Vanessa had well-developed cellulite on her exposed thighs, muscles retreated into the warmth of fat. They just looked at each other, wordless, but we all knew Ms. Lancaster was pleading, trying to declare her heart as less than guilty. We remembered how they behaved before they knew we were watching, how easily they moved around the lab, living without an audience, assisting and being assisted, content. Now, Vanessa waited patiently for Ms. Lancaster to remove her grip, and that was it. In those couple of seconds, they danced for us, or so it seemed, sequined under watery light. They were our tragic opera. How their song made us tremble.

Right before the semester ended, we had to present our final bones. The last step was to affix tiny labels on all the differently colored parts. There were no clear grading criteria, so that meant make it neat, and it’s complete. Secretly we had high hopes for the final conclusion to this brutish endeavor, feeling like the ancients preparing a sacrifice to the gods. There should’ve been a required bed of herbs to lay the bones on, silver trays or an altar of alabaster stone, but it was just a cold, steel counter etched with years of penises and profanity. The bones were not glorious, were not brilliant or bright. They were just ham-fisted, dreadful, clubs to beat down our expectations. Vanessa had already gone for good, failed for non-attendance.

Ms. Lancaster made it to the end, the very last day, before she disappeared too, never to return to campus. On that last day, we already knew she wasn’t coming back. Her glow had been on the decline for a while, and seeing her was like watching something grow in reverse, a plant return to a seed or an old television power down, its light extinguishing from the outside until it shrinks to a single dot and then it’s gone. By the last day, she’d disappeared the way paper disappears when it’s crumpled and wet and becomes so unrecognizable, it is not even understood as paper anymore but something else, something to be discarded by those who can handle wet and dreary things. Someone must love her somewhere. Or not. Maybe because she had so many animals to take care of.

After Ms. Lancaster made her final exit, Elizabeth showed up suddenly, the bird’s blue head swiveling happily, its belly full of seeds.

No one wanted the animals to suffer.

It was probably for the best that Elizabeth was nabbed earlier, seeing what a wreck Ms. Lancaster’s rental house turned out to be. There wasn’t as much blood as people think, really. Some of the animals did get out of their cages and roam free in her absence, but most just died from dehydration. Many lived though, the ones that got out or the ones she’d always left uncaged, the ones that knew where to look for sustenance, how to hide from threats, how to take enough and leave enough. Those are the ones that always survive. It’s a shame even survivors eat each other in the end.