TWENTY-FOUR KARAT

Karen Gu

She doesn’t know it yet in the waiting room, but her stomach is bleeding, its structure compromised. This beautiful country ate a hole in it with its heavy, bland food, tongue-twisting words, its cold distance. The doctor tells her it’s an ulcer, asks if she is under any stress. She nods but doesn’t elaborate, her mind already drifting elsewhere.

She is studying to be a structural engineer. The professor assigns the final project on shell structures, thin surfaces curved into concrete domes, sweeping concert-hall roofs, and arching ribbon bridges.

Her stomach is a shell, she thinks, a thin shell of muscle. She will build a mathematical model of the human stomach to show its weaknesses, where it is prone to collapse, where it could be reinforced. She will make a shield for the stress of her new life. In her notebook, written in blue crystal Bic:

Q: How much stress can the stomach lining endure before it is stretched too thin?

Watch, she will build a new life here against all odds, amidst fields of Idaho potatoes. Mashed potatoes in Chinese translates into 土豆泥. Isn’t that what she saw when she first moved to Idaho from China? Potatoes and dirt.

She left everything to come here like so many before her and so many after. Her great-great-great grandfather went to California to pan for gold. When he came back, he buried it in a patch of land. When the family went hungry, no one could remember where the gold was or how much was there. It was paid back to the earth.

* * *

She’ll never go there, but Strychnine Creek is an hour’s drive away from campus. One hundred years ago, Chinese miners found gold at a site abandoned by white miners. The Chinese miners diverted water from a nearby creek into their camp for washing off the day’s work, the dark grit under the fingernails, the accumulated dirt on the neck, behind the ears. They used it for cooking too. For boiling up recipes of home.

The white miners, mouths bitter with jealousy, poisoned the Chinese miners’ water supply with Strychnine—rat poison. It causes the muscles to spasm, the body to convulse for hours until death by asphyxia. The camp was strewn with bodies, rain-sodden, veined with poison, picked clean of gold.

On a treasure-hunting forum years later, long after she has moved away with treasure of her own, someone is looking for the camp. They want to look for gold caches because of “the Chinese habit of hiding their gold.” Even if they don’t find the stolen gold, they’d be stoked to find the location, some tools. They ask for tips. Five hours away from Strychnine Creek is Chinese Peak, named for a Chinese man who died there. There are so many places here named after dead Chinese.

* * *

She has the key to the cadaver room. Her friend from the med school fished it out of his pilled lab coat, yellowed at the collar. He told her he had stomach measurements from his anatomy textbooks, that he could help with her project, but she insisted. She wanted to go alone, she wanted to feel the stomach with her hands. The key turns. She fumbles for the light switch, gagging at the stench of formaldehyde. Scared that a cold hand or foot might reach out and touch her.

There are ten cadavers covered in white cloth, the corners of plastic body bags poking out underneath. She almost leaves but finds her nerve. She unzips the nearest body bag and reaches into the deep incision that opens up the body, careful to not look at the face. As she lifts the sheet, she notices the body’s long silver chest hairs.

The flesh is cold, pickled in chemicals, in poison. Her fingertips search for the stomach. There is the folded, textured muscle, curved like a bean, drained and cleaned of all its gastric juices. This is a stomach that can’t attack her, that won’t draw blood.

Her fingertips press against the ribboned walls of muscle, and she marvels at this flexible organ and wonders how a wound ate through her own stomach. A minute more, she promises herself. Keep drawing the shape, measuring the thickness of the stomach wall, of the muscle membrane. She will use this data, will transfer the lingering formaldehyde in her fingertips to a computer keyboard and render her shell model. Then, her gloved hands knock into a foreign object: angular, cold, and heavy. Even under the artificial light, it shines with a worn luster. A gold ingot.

She slips it into her pocket, covers the body, turns out the light, and the door locks behind her. Her sweaty palms have slicked all the powder away from the inside of her gloves. In the hallway restroom, she washes the ingot in the sink, unsure if it’s her gloves, her hands, or the gold that still smells like formaldehyde.

The ingot is brilliant yellow, heavy and hard but softened at the edges. She wonders if she should send it back home, but how could she explain its provenance? She wants to ask the medical student about it but is too scared to share her secret. Under her poly-filled pillow is the ingot and a dull chef’s knife.

* * *

Decades later, and gold is on the menu. It’s opening night. Gold dust clings to the sweaty foreheads of the line cooks, it settles into their mise-en-place, making everything shine. Gold leaf. Gold flake. Gold foil.

Painted on plump berries and dusted onto patisserie. Brushed onto bites of caviar and foie gras and king crab. Snowglobed in bottles of clear liquor. Tweezered onto delicate garnishes of micro herbs and edible flowers.

Edible gold has to be twenty-four karats in order to ensure its purity. There are small amounts of silver and copper alloyed with the yellow gold, but all the quantities are carefully monitored to prevent toxicity.

There are so many questions she will never ask:

Q: How many sheets of gold foil can be made from one gold ingot?

A: She’ll never know.

Before the gut renovation, the new kitchen and appliances, the custom tile and fixtures, the interior designer, restaurateur, and rising star chef, this building was vacant for a long while. Many years before that, it was a Chinese restaurant. This was where she bussed tables the summer she burned a hole in her stomach wall.

She carpooled from Idaho to Seattle with a group of Chinese students to find work. On the way there, she sat next to a chemistry student on his way to fish for king crab off the Alaskan Coast.

“I’m going to be rich,” he said in the car. “I’m going to eat crab legs every day,” he laughed.

She thought about going with him, but she settled for the restaurant. She wore through the soles of her cheap shoes on the stone floor. Her feet ached and blistered, skin smarting and puckering, leaking pus.

In her shared sublet after another long shift, her body hurting from walking around the restaurant all day, she wondered if she should have followed him onto the boat. The money would have been so much better, and she was in pain for pennies here. When she goes back to campus in the fall, she will be pissing blood.

Her last winter in Idaho is bitter cold like every other winter in Idaho. The wind seeps into her studio apartment through drafty windows. She has no private bathroom, no stove, only a hot plate. She subsists on chicken, rice, and milk. She cooks the rice in the milk. Milk porridge. Hot, white slop. She boils the chicken on the hot plate. It’s cheap. It’s easy. It’s all she can afford.

When she starts her own family years later and miles away from this cold and unforgiving place, she will never cook chicken for dinner.

Q: How long would it take to melt gold on a hot plate?

A: The plate would never get hot enough.

She had wanted to design shells, to stretch force over curved planes of concrete that would cut across the sky in graceful swoops. No one wanted to build them. They are expensive to construct and even more so to maintain. What people want is sharp angles, neat and orderly geometry.

It doesn’t take her long to move on, to move forward to something else. Or is it moving backwards? She settles into a gray cubicle, and the only things she builds are contained in the small, bright screen of her desktop computer.

* * *

Now, thousands of miles away from Idaho, she is a mother. In the grocery store, rotisserie chickens will beckon with their burnished bronzed skin, the heat lamps dispersing their aroma through the aisles, but she will breeze right past them to pick through produce. The automatic vegetable misters dampen her shirtsleeve, looped audio of tropical birds plays through the cool spray, but she continues to examine the cabbages, the carrots, the celery. Back then she couldn’t afford to eat vegetables, now she puts the best specimens in her cart.

She picks out a box of instant mashed potatoes from the shelf. When she shakes the box, it sounds like flakes of oatmeal, like rain. She selects a pristine box from behind the front display. Here is crisp cardboard, without dented corners and the oily residue of other shoppers’ fingers. She asks her daughter to follow the instructions, and it tastes like gluey nothing.

* * *

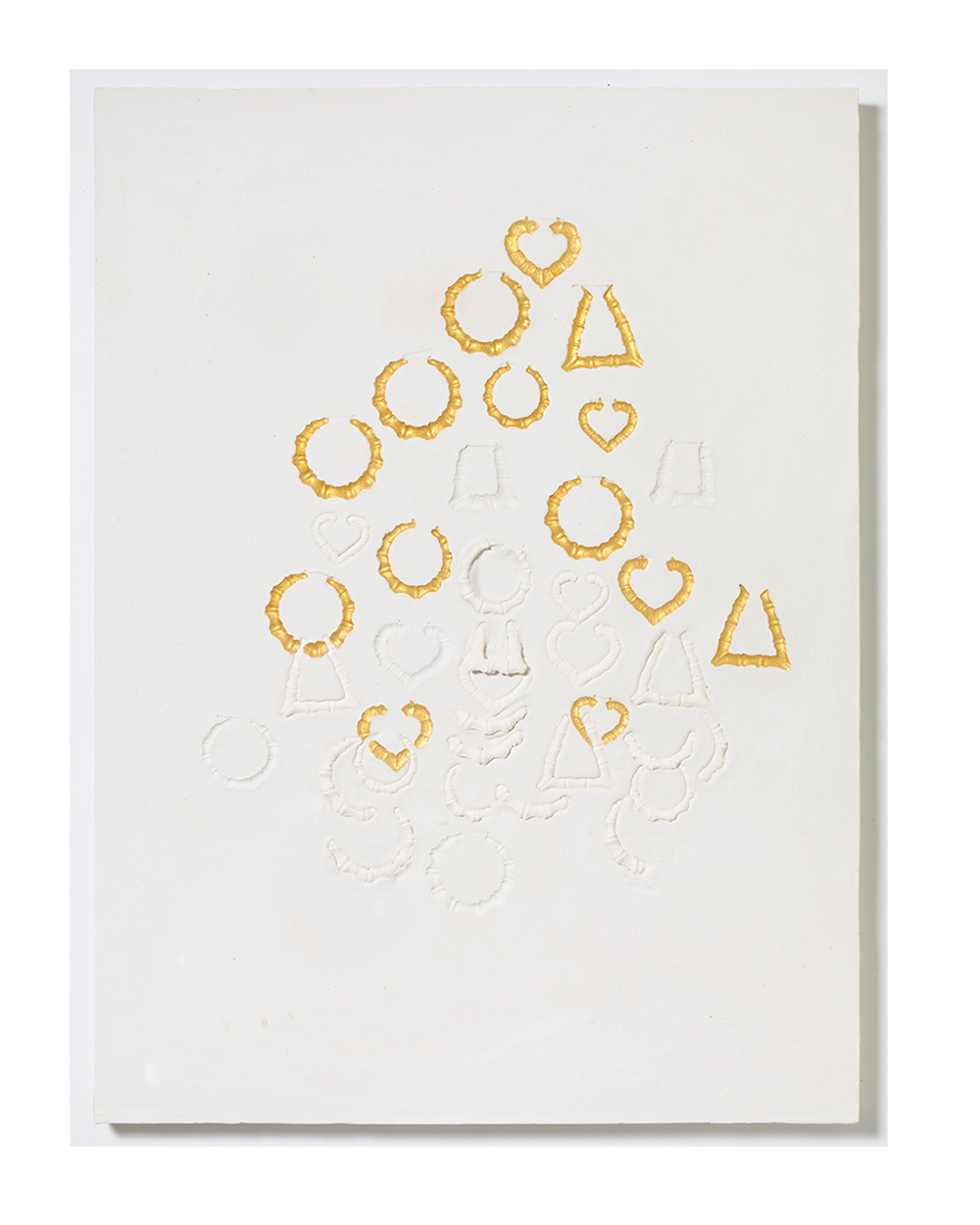

On her next trip to China, she will fill an empty suitcase with pounds of jewelry: necklaces of polished amethyst and rose quartz beads, pendants of iridescent opal, leaden bracelets of hematite that clack cooly on the wrist. She has some money now, and her dollars go far back home. She drapes her neck with stones, offers them to her daughter as playthings. Her daughter doesn’t mean to crack the jade bracelet. It was an accident.

In school, her daughter will have an earth science unit on rocks and minerals. The school has brought in a mobile gem mining experience. Outside, there are buckets of sand, one for each student, hiding minerals and common gems within. A small sluice is set up, modeled after real Gold Rush sluices, says the teacher.

Her daughter dumps her sand bucket into her screen box and shakes the sand in the water, sifting away the rough grit. The playground blacktop radiates heat. The sun is warming her neck, and the cold water of the mobile gem mine cools her even though her fingernails are clogged with sand.

She sifts and sifts until all that’s left in her screen box is a cluster of dull rocks. She can’t tell because they’re still dirty and unpolished, but there are three emeralds and two rubies in the rubble. The only thing that shines is a hunk of glittering pyrite. Pyrite is known as fool’s gold.

Q: How can you tell pyrite from gold?

A: Fool’s gold will shatter under blunt force. Real gold will stretch and bend and thin.

After her mother tells her the pyrite isn’t real gold, the daughter rummages in the red velvet jewelry box on her mother’s nightstand. It’s lined in pink satin. There are two levels and a beveled mirror inside the lid. In the second drawer, all the way in the back-right corner, is something small and hard. Wrapped in old Chinese newspaper. The gold ingot.

* * *

The daughter knows the story of her mother:

Before America, see her farming under the hot sun. Her thin skin baked brown and seasoned with sweat. The months she worked in the fields, eating bowls of white rice. The time after, in a small, rented apartment with her roommate, bored out of their minds, with no hope for their futures, she points a small pistol at her bedroom door, squints her right eye and fires because she can, studding the walls with holes.

See her steal from the market, sneaking oranges up her sweater sleeves. The famine of her childhood is over. No more sneaking food from the family larder. No more beatings when she was caught.

Conditions are improving, more and more of her friends have hope but not her. The world is changing around her, and she wants to change too. A friend of a friend moved to America, and she, recalling her great-great-great grandfather who mined the gold mountains of San Francisco, decides that she will too. There is a saying: that the streets are paved with gold.

But not so fast. She pays her own way there and is as poor as dirt. The streets are not paved with gold, but they aren’t dirt either. They are smooth, gray concrete, a sturdy and practical building material.

There are so many questions she will never ask, and I know all the answers.

Q: How many sheets of gold foil can be made from her gold ingot?

A: Her gold ingot can be beaten into one 321.5 square-foot sheet of gold foil. Enough to gild a square mile of paved concrete.

What the daughter doesn’t know is that when her mother is a busgirl, the waitresses don’t share their tips, and she is being paid under the table, so what can she do but wash the smell of sauce out of her hands and hair and then do it all again. It wasn’t enough to save any money, so she looked for other work in the newspaper.

First, she answers a caretaker ad with a high hourly rate. A frail, old white man opens the door. The house smells sour with sickness and disinfectant. She sits while he fetches the uniform, black pleather bra and panties. He asks her to let down her hair. She tells him she can’t do the job. He offers her twenty dollars for her time, but she leaves the money on the table.

Then, an interview for a housekeeping job an hour outside of the city. The house is grand, polished with the shine of new money. She is to look after a seven-year old boy, the son of software executives. His mother breezes in wearing a brown silk suit and looks her up and down. Her son follows on her heels, whining, “Mommy, will this maid steal from us too?”

The husband blushes and waves off his son. He offers her the job. He also asks if she might know of any men who might help move their new treadmill upstairs to their home gym. She doesn’t know anyone. She’s from out of town, she explains. Then would she help him move a few things today?

She is small, but she is strong. In high school, she ran track. She was a sprinter. Even now, you can tell she was fast. Her bones are thin and efficient. When she had knee pain, she treated herself with acupuncture. Sterilized the needles in a blue flame and stuck them up and down her legs. Later, she will shop in the department store’s petite section while her daughter, tall like her father, browses the junior fashions.

But wait. Watch this wealthy, white man ask her to help lift what he can’t, his face turning pink, a vein on his forehead straining from the effort. She feels a sharp pain in her stomach as she braces under the weight. Together, they move the treadmill to where it needs to be.

Winded and doubled over in pain, she tells him she cannot take the job. He buys her a McDonald’s burger and offers her some money for her trouble. She doesn’t take it. That night, in the one-bedroom Seattle sublet she shares with six other students, blood swirls into her urine.

Q: How is gold foil made?

A: Blunt force. First stretch the gold through heavy, metal rollers until it becomes a ribbon. Then cut it into small pieces, about 6 square centimeters each. Layer each golden sheet between paper and place it under the pounding machine until it spills over the edge. Continue the same process with larger and larger sheets of paper until the gold is beaten and thinned to your desired dimensions. A violent alchemy.

* * *

The daughter grows up overhearing her mother and father fighting about money, screaming at each other about how much they could afford to send overseas to their families. Then, after years of living in apartments, the family buys a house. They celebrate at a Chinese buffet tucked into a suburban New Jersey strip mall. The daughter watches her mother pile her plate with crab legs, cracking them to reveal strips of coral meat. The mother offers the crab to the daughter, pushes it onto her plate.

In the new house, the mother has a walk-in closet. To the daughter, it is a dress-up wonderland at first. The daughter tries on sheath dresses that become gowns on her 8-year-old frame.

When she is a teenager, the daughter sees the closet for what it is: a sea of blue, black, and gray skirt suits. One day she rustles the hangers around, looking for something just out of reach. The leather purse still in its dust bag, the black turtleneck sweater. But there’s a golden glimmer amidst the shoulder-padded blazers, the business-casual blues. Three golden dresses of lurex, lamé, and fish-scale sequins. A polyester portal to nowhere.

Q: Where in the closet is the jewelry box that contains the newspaper-wrapped gold ingot?

A: Hidden under the hems of the golden gowns and forgotten.

When she gets her first job at the mall, the daughter and her mother watch the Gold Elements man dab lotion on an old lady’s face. He promises anti-aging, antioxidants, and illumination. The old lady peers in the mirror, turning her head back and forth, her creped skin glimmering with microparticles of real gold.

The mother wants to try the lotion, and the daughter is embarrassed. Her mother closes her eyes as the man pats glimmering cream on her orbital bone. The daughter’s hands itch. She spent her last hour at the store detangling jewelry, long pendants and delicate chains. It was the nickel. She’s allergic, and the next morning she’ll have small, pink blisters on her hands. When she gets her ears pierced, she will realize that she can only wear gold.

A new kiosk moves in front of the food court. In front of the McDonald’s and the Cold Stone Creamery, amidst the mall goths in their black platform shoes and sky-high spiked hair, a man in a baggy suit with slicked-back, thinning hair tells passersby that he’ll buy gold for cash.

* * *

Gold is a noble metal. Yes, worn by nobles and lustrous with wealth, but chemically, it’s noble like the gases. It won’t react and corrode in the air, won’t spark and combust. It maintains its brilliant composition. Precious and noble metals are not the same, but gold is both.

Q: Is it noble to not react? Is it noble to stay the same no matter the circumstances, no matter where you are and where you come from?

A: The gold won’t answer.

Q: How did the gold get into the stomach?

A: It was panned and mined and stolen, and then it seemed like there was no more, but there was. In the water, in the soil, in the roots of the plants, and in the bellies of the livestock. Farmed and foraged and processed and cooked and digested. Churned through bile and pressed into a sturdy ingot by strong stomach muscles, for safekeeping.

This is an immigrant story. Which is to say that this is a tale of suffering, gilded with poetic justice. Which is to say that this is a fairy tale, spun from pyrite instead of gold.