When I received an early copy of Marriage of a Thousand Lies (June 2017, Soho Press), I was immediately intrigued by the novel’s premise—Lucky is a queer Sri Lankan woman with a gay husband. In her marriage of convenience, her family doesn’t have to know about her sexual identity and she can date who she wants without judgment from her Tamil community. But what happens when Lucky must return home, and when she discovers her first lover, Nisha, is getting an arranged marriage?

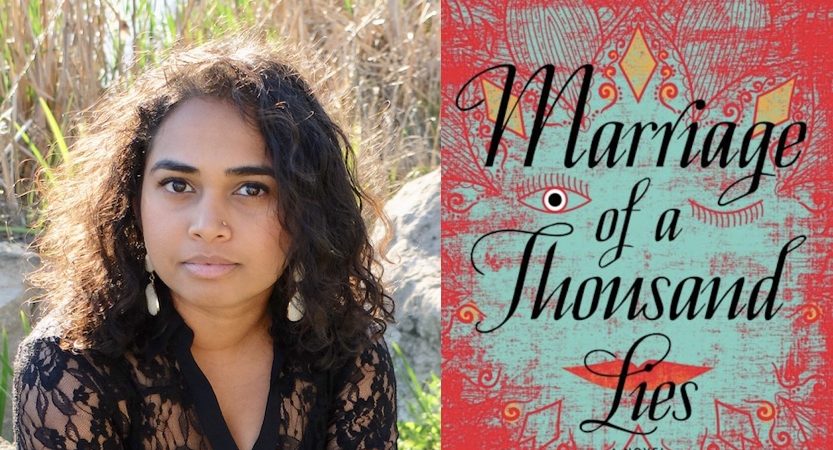

SJ Sindu’s debut novel, recently published by Soho Press, explores South Asian queer identity in America, the struggle between community acceptance and authenticity to self, and the boundaries of familial love. In our interview, I spoke to SJ Sindu about why she wrote this story, modern arranged marriages, the Sri Lankan War, and her writing journey.

—Crystal Hana Kim

Crystal Hana Kim: Your debut novel, Marriage of a Thousand Lies, was published this month. Congratulations!

Although this is your first novel, you also have a hybrid fiction & nonfiction chapbook, which came out last year. When did you begin writing, and what was the journey to publication like for you?

SJ Sindu: I’ve been writing since I was seven years old, since I learned English. To me, Tamil, my native-language, is the language of poetry, but English is the language of narrative. When I was young I’d write stories inserting myself into the shows and books I liked. As a teenager I wrote fanfiction using other people’s characters. It wasn’t until college that I started writing original stories with my own made up characters. The hybrid chapbook, I Once Met You But You Were Dead, is full of stories, essays and poems I wrote when I was in my Masters program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The journey to publication was a long one. I had a lot of help from mentors along the way—my professors, mostly—and the support of my writer friends. But it was a slow, long road of clawing my way up, as I think it is for most writers. Still, I’d say I was lucky to have published at all. I was definitely lucky to have caught the attention of editors who believed strongly in my work—specifically Amanda Miska at Split Lip Press (who published my chapbook), and Mark Doten at Soho Press (who is publishing my novel).

CHK: I’m so glad your novel found a home—especially because I think its subject matter is important and necessary. Marriage of a Thousand Lies is about Lucky, a gay Sri Lankan woman who is married to Kris, a gay Sri Lankan man. Their marriage is one of convenience—their parents do not have to know about their sexual identities, and they can continue dating freely. I was immediately intrigued by this premise, particularly because I hadn’t read a book about a queer South Asian woman before. Why did you decide to write this specific story?

SJS: I wanted to write it because it’s an important story, and one that isn’t being written about much. I can count the novels about South Asian queer women on one hand. I’m going to quote Toni Morrison here and say that I wrote it because I wanted (and needed) to read it.

CHK: Did you tell your family or others in your Sri Lankan community that you were writing this book?

SJS: I didn’t tell them! They knew I was writing a book, but I was often very evasive about the contents. I wanted to be fully invested in the story and I wanted to love my characters, and I knew that would be hard if I faced a lot of negative feedback early on. I didn’t want blank stares or disgusted looks, so I just didn’t tell anyone in the Sri Lankan community what the novel was about. Now, I did tell people my age what I was working on—young Sri Lankans and Indians, and desi writers, who tend to be more liberal and open minded. And I got a lot of good feedback from them.

CHK: That’s great to hear you received support from the younger community! I’m sure there’s a lot in this novel they can relate to, especially about identity and balancing American and Sri Lankan cultural values.

One of the central themes in Marriage of a Thousand Lies is the modern arranged marriage in America. I know some acquaintances that have taken this route, but I think that many who read your book will be surprised to see the pressures some face to find a suitable arranged marriage. Can you tell me more about your decision to explore this topic in your book?

SJS: I know that arranged marriage is something many desi writers explore in their work. But I wanted to dive deep into what arranged marriage looks like right now, nestled within modern day Western culture. A lot of people back home and in the diaspora will defend arranged marriage, saying that it’s so much freer and more flexible than it used to be, like a modern dating service. That’s the line they use. But the problem is that for some people, the choice isn’t really there. A lot of people are still forced or coerced to go through with it. The pressure for me was immense from the community, and I know a lot of others who have felt that burden. It’s a very complicated issue, with many layers and nuances of choice and community pressure, so I wanted to explore what that’s like for someone like my narrator Lucky, who is very Americanized.

CHK: Lucky escapes an arranged marriage by choosing Kris. Nisha, Lucky’s best friend and first lover, seems to fall into her arranged marriage as a way to deny her sexuality. Why did you have these central characters approach their sexuality in such different ways?

SJS: It was important to me for my characters to all make different choices when faced with similar pressures. All the women in the novel are dealing with cultural misogyny and patriarchal oppression, but they all choose different paths. Similarly, I wanted my queer characters to choose different paths. I know a bunch of people who have chosen, like Lucky, to have marriages of convenience. But I know a lot more people who are like Nisha, who aren’t fully comfortable with their sexualities themselves and so they deny it. Usually those stories don’t end well. I guess to me this novel is as much an exploration of that choice as it is a warning.

CHK: So much of this story is about Lucky grappling between owning her sexuality at the expense of losing her close-knit Tamil community or vice versa. It’s heartbreaking, particularly because she knows she wouldn’t be the only one exiled—her mother, who is already somewhat shunned for being a divorcée, would also feel the repercussions of Lucky’s decision to ‘come out’. What was it like navigating this issue through your writing? I can imagine it would be emotionally difficult to inhabit this space every day.

SJS: It was excruciating to go back to this headspace day after day. But then again, I’ve grappled with similar choices, so it was familiar territory. I think that’s partly why this novel took so long to write—eight years from when I started to publication. I worked on a lot of side projects so that I could breathe. I sometimes resisted coming back to the novel, because I wanted to be free from Lucky’s internal cage. But at the end of the day, Lucky’s story is so much a part of my own story that I had to write it.

CHK: I also enjoyed the many other complex relationships in the novel, like Lucky with her estranged sister Vidya, who left her family behind when they wouldn’t accept her black boyfriend. And Lucky’s mother’s relationship with Aunty Laila, who used to be her best friend and has now married her ex-husband. These characters are multifaceted, flawed, realistic. From a writing process standpoint, how did you keep track of all of these interconnected relationships, with all their intricate emotional tangles?

SJS: The long writing process took care of some of that. I spent a lot of drafts getting to know the characters. It took years before I felt like I knew them as well as I know myself. In each draft, I would plunge deeper into their relationships with each other, and each pass in revision added more and more complexity to each character and each relationship. What you see in the novel is the product of almost twenty drafts laid on top of each other.

CHK: I’m curious about one of the subtler undertones in the novel—the Sri Lankan Civil War. The reader learns that Lucky’s uncles did not receive a lottery visa and thus never made it out of Sri Lanka, that Lucky’s mother escaped riots during their college years by hiding in a nearby farm, and that Aunty Laila’s husband and son died in a bus bombing. Did you know from the beginning that your characters would have these past experiences rooted in the war or did this come through after multiple drafts?

SJS: I think it’s impossible to write Sri Lankan characters without their having experiences in the war. So many people in so many generations were shaped by the wars, some directly like Lucky’s mother, and some indirectly like Lucky herself. Trauma doesn’t just disappear—it is passed down from generation to generation, it lives in the spaces between conversations and manifests in how people respond to fear and grief. Lucky’s mother in a lot of ways is a product of war, and to me that makes her an interesting and complex character. I knew from the beginning that the older characters—the ones born and raised in Sri Lanka—would have war trauma, but I found out exactly what that was through the actual writing of drafts. The war stories told by Laila Aunty and Lucky’s mother, for example, were a late addition that I think turned out to be absolutely essential to revealing the two characters’ relationship and why they still tolerate each other. High trauma often bonds people, and these characters cling to each other in a way they might not otherwise, because they’re the only ones who understand.

CHK: I find the topic of trauma fascinating. My novel starts with the Korean War, and I’m very interested in how characters’ endure and process war. I can see how Lucky’s mother finds comfort in her traditions, despite the oppression and misogyny, because they provide a sense of order and safety to her world. Has the Sri Lankan War affected your family, and if so, do you think that has influenced your writing?

SJS: Definitely. My family is Tamil, and I spent the first seven years of my childhood in the northeastern regions of Sri Lanka, where much of the fighting was happening. I remember sitting in a makeshift dugout bomb shelter during air raids. I remember leaving our house at night by foot because the front line was getting too close. I remember a lot of checkpoints and soldiers with guns. I remember not having electricity or running water. I think all these experiences absolutely shaped me and my writing. This, I think, is partly why my writing voice tends to be lean and precise rather than meandering and beautiful like a lot of Anglophone Indian writing. The literature in which I first found reflections of my own war experience were masculine and American—Hemingway, Tim O’Brien, Vonnegut—and my writing style took after those writers instead of people with whom I share the literary identity of South Asian heritage. I also think the war drew me more to characters who are not only dealing with inner turmoil, but also struggling against a world in which they are hunted and oppressed.

CHK: Your early years in Sri Lanka sound frightening. I admire how you’ve incorporated this traumatic history into the novel, how you’ve used the war to strengthen relationships between your characters. To end our interview, I’d like to move from the past to the future. What are you working on now? What new works should your readers anticipate in the years to come?

SJS: Right now I’m working on my second novel, currently titled Blue-Skinned Gods, about a young boy who becomes the center of a Hindu cult in India. I hope to have a draft for submission by fall. I’m excited about this project because it’s such a departure from Marriage of a Thousand Lies, but at the same time, it’s similar because I am drawn to characters and stories of isolation and identity-seeking.

CHK: The novel sounds interesting and very different! Well, thank you for taking the time to talk to me today. Marriage of a Thousand Lies broadens the LGTBQ+ canon in new and important ways, and I’m so happy Apogee was able to learn more about your work. Congratulations on the publication of your ambitious debut novel!

SJ Sindu was born in Sri Lanka and raised in Massachusetts. Her hybrid fiction and nonfiction chapbook, I Once Met You But You Were Dead, won the 2016 Turnbuckle Chapbook Contest and was published by Split Lip Press. She was a 2013 Lambda Literary Fellow and holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Florida State University. Marriage of a Thousand Lies is her first novel.

SJ Sindu was born in Sri Lanka and raised in Massachusetts. Her hybrid fiction and nonfiction chapbook, I Once Met You But You Were Dead, won the 2016 Turnbuckle Chapbook Contest and was published by Split Lip Press. She was a 2013 Lambda Literary Fellow and holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Florida State University. Marriage of a Thousand Lies is her first novel.