The Lover or the Fighter

by Ian E. Toledo

It happened during either my sophomore or junior year as an illustration major. I was still struggling to overcome my middle school rep as both shyest and quietest student and was taking a course called Sequential Illustration. The course was taught by a professor who I’ll call Mr. V, an elderly man that’d had a modestly successful career as an illustrator and was pretty well known and respected in some circles.

One day Mr. V. gave us an assignment to do a series of comic pages on whatever subject we wanted. Despite the fact that I adored comics, nothing immediately came to mind. So when he came around to check my sketches I looked up at him helplessly, hoping that he would share one of his idea generating methods he had acquired from his career as a successful illustrator. Mr. V’s sage advice was, “Why don’t you draw something about food? Why don’t you draw egg foo young?” Then he looked at me and proceeded to laugh in my face.

I was shocked that someone in such a position would say that to me or anyone. A flood of Weltschmerz pumped through my veins. Half of me wanted to cry in disbelief and disappointment that people still think this way, the other half came close to punching his lights out. Instead I just stared at him and said nothing. It took everything in my power to stifle myself from going amok on this guy. Eventually he must have felt awkward and moved onto the next student. I couldn’t believe how much he’d generalized and assumed just by looking at me, without knowing anything about my true identity or that of my family.

Depending on my hair length, if I wear glasses or not, and the current degree of my suntan, I often get asked what type of Asian or Southeast Asian I am. Sometimes people ask if I’m Polynesian, American Indian, or Spanish. One time I was even asked if I was Italian from another Italian person. In college I would find myself on the receiving end of mocking Buddha bows, Japanese air karate chops punctuated with loud”Hi-ya’s!”, the occasional “ching-chong” outburst, but mostly lots of Bruce Lee “Wah-tah” taunts from non-Asian strangers. And while I am a big fan of Bruce Lee, I am not Chinese, I am a Filipino born in America, a.k.a. Filipino-American.

In some of these strangers I could see the “yeah whatever, same difference” in their faces if and when I corrected them.

So what could I do? How could I show the amazing complexity of my culture to a supposedly higher educated person who should know better? Would punching a professor prove that it is wrong to make such gross generalizations?

How could I show the love and sacrifice my parents had for me? How could I teach this man of our labyrinthine history? Our beautiful identity crisis?

Filipinos mixed blood heritage reflects the beautiful languages of Malayo-Polynesian, Spanish and more (Asian, South Asian, to Aboriginal, the list goes on and on). We are much more than a mix of east meets west. We confuse people. Our cultural and genetic make-up blows dichotomy out of the water. We don’t fit into their boxes. We break out of them.

How could I present my true identity without sounding too confusing, too proud, too ludicrous? And on that mostly white campus, how could I say this without losing friends? That’s when it hit me. I decided to make a comic about old Philippines for my assignment. I can’t remember if my reasoning was that people should rejoice in the truth, that the truth would set us all free, or if I was just too angry to care. But I do remember one thing; it was the first time as an artist I was really in the zone.

I was pumped that our assignment took the form of comics. What better way to reach the masses? I was inspired by comics that depicted and were created by other less “showcased” cultures. I was inspired by Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Dwayne McDuffie’s Milestone Comics run. Both of which were just coming out at the time. I referenced Jack Kirby, Burne Hogarth and the Filipino artist, Botong Francisco. I decided to go back to the beginning, the beginning of our historic identity crisis.

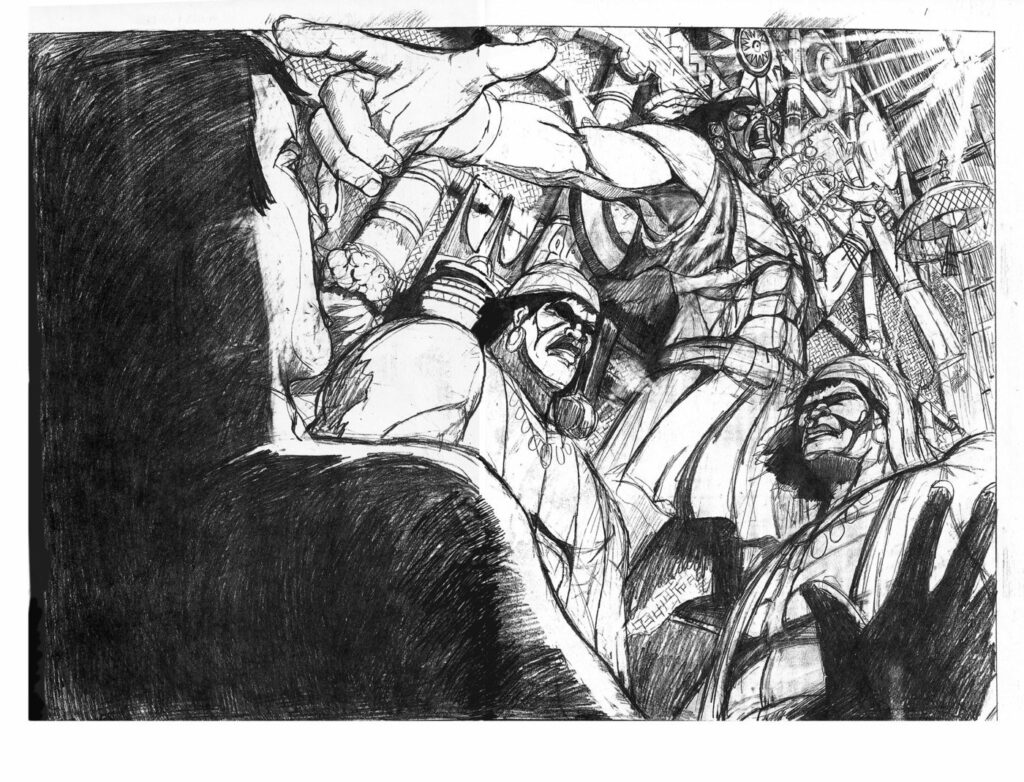

This picture is of Lapu-Lapu: the long haired, tattooed, larger than life warrior chieftain of the Philippines. He is the one who first resisted and defeated the Conquistadors from Spain during the Battle of Mactan in 1521, where Ferdinand Magellan was killed. Eventually the Spanish did take over the country and reigned for 400 years, although they never conquered the south. They referred to us as indio, meaning Indian, from India. (I don’t know why they kept making that mistake). The term eventually gained a double meaning: savage.

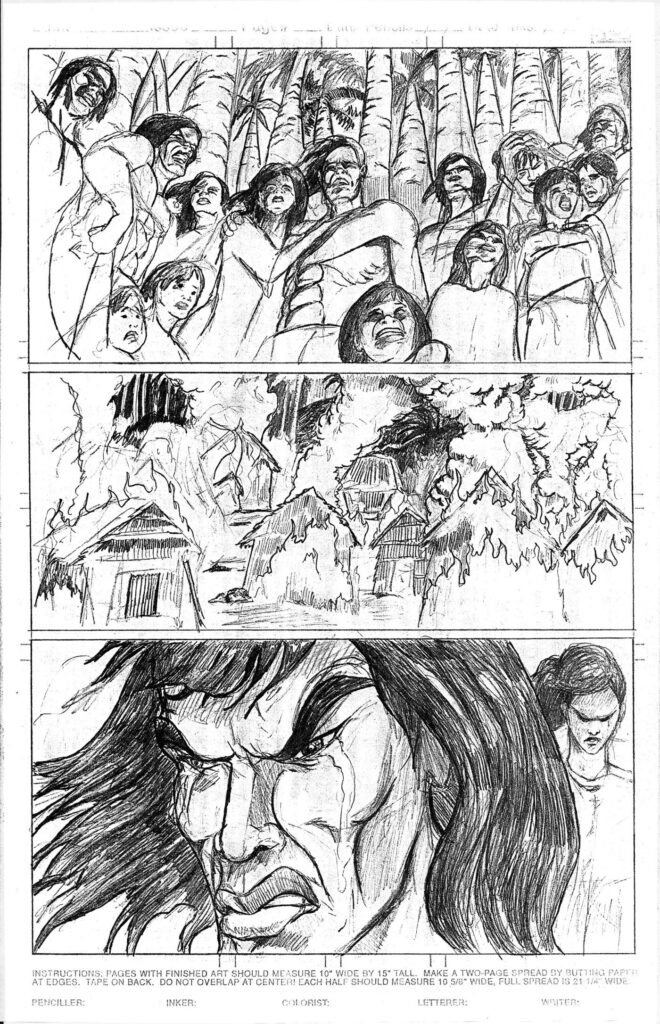

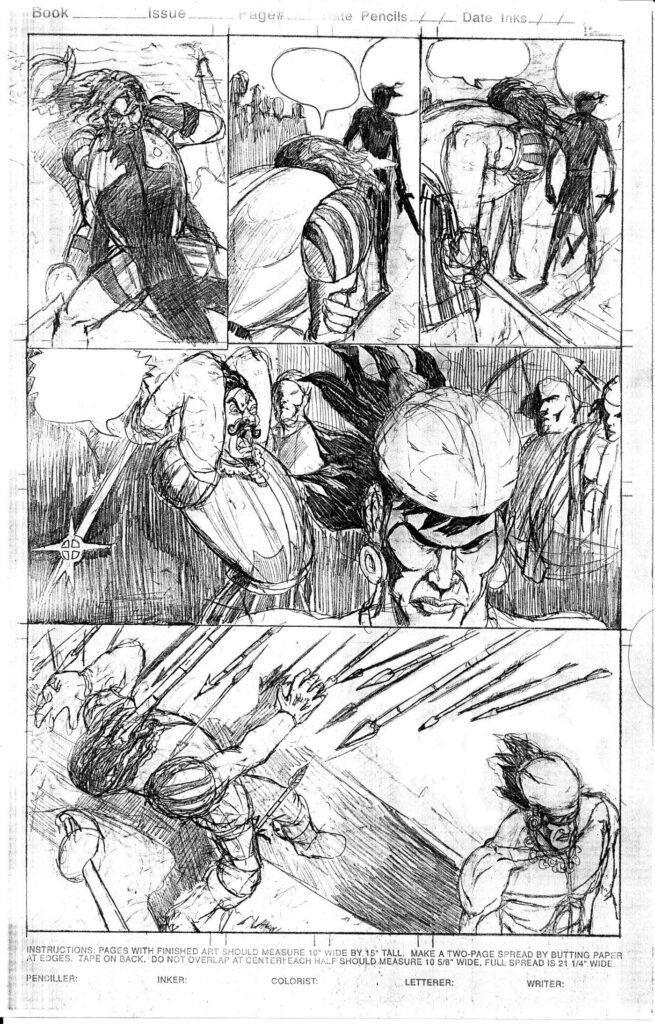

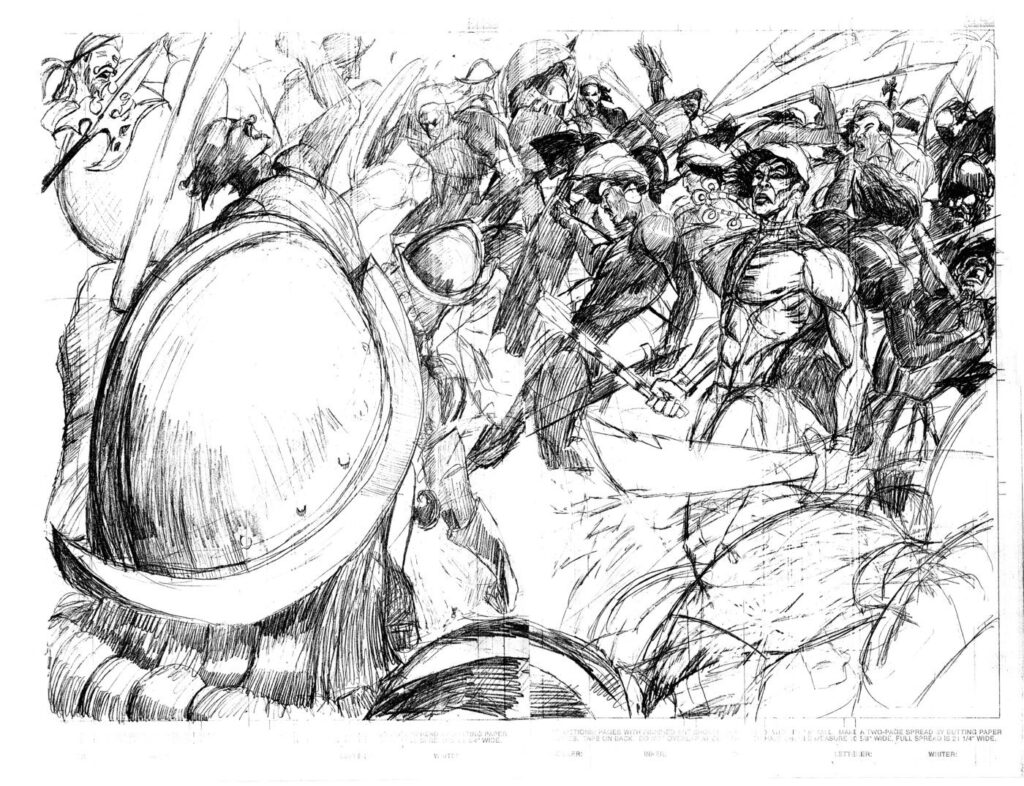

After researching books from the Philippines (the details aren’t in U.S. history books), I tried to sequentially tell the story of the people of Mactan — people known for their love of freedom — and their battle against the forces of Magellan. The conquistadors performed a demonstration of Spanish armor to prove to the natives that they were invincible and had superior weaponry, but some of Lapu-Lapu’s tribe saw that the armor had weak spots. Later Magellan baptized chief Humabon a puppet king for the Spanish crown. All other chiefs were to kiss this new king’s hand, convert to Christianity, bow down to King Charles the I of Spain. Only then would Magellan’s forces let them live. But Lapu-Lapu, who knew that Humabon, Magellan and King Charles were also asking for his people’s land and subservience, told Humabon to go back to Magellan and leave their land. The Conquistadors, with the help of their converted “indios”, burned the village at nightfall.

Lapu-Lapu and the survivors who escaped got ready for an inevitable battle. The Conquistadors were armed and fully armored. Their technology might have seemed like an unfair advantage with their galleon cannons, rifles, armor, and Toledo steel swords (yes, that is where my last name comes from), but these indios knew how to use their Kampilan swords, knives, spears, and bows and arrows. They were also the originators of a martial art known as Arnis and Kali, a deadly and effective combat style later adopted by the U.S. Navy SEALS. The oppressors were in for a rude awakening.

I drew a sequence where Lapu-Lapu and Magellan fight. (No one really knows if these two actually met in battle, so I took some artistic license.) Lapu-Lapu parries and strikes with the same sword hand, strikes with the other and knocks the mighty explorer down with fatal wounds. I referenced Bruce Lee fight choreography where he used Arnis/Kali sticks, because Bruce Lee was a genius who appreciated what other cultures had to offer. The chieftain turns around, knowing it’s finished. The conquistador screams back, “Don’t you turn your back on me, indio!” but then (as some accounts say) the great Portuguese explorer gets shot with a poison arrow in the leg and speared in the face. I subdued that goriness by hiding the actual impact with Magellan’s hair. (My being brought up and Roman-Catholic, due to that 400 years of Spanish reign, still subconsciously influences my aesthetic choices). Lapu-Lapu walks coolly off not wanting to waste his breath on such a deceiver.

I wasn’t taught about the Battle of Mactan when I was young. Learning about it was like finding a missing piece of my identity. It’s like I got a blueprint showing me how resistance was done long before I came to be. To me it felt like it was happening all over again but on a different battle ground, with words instead of swords. Instead of having to kiss the hand of the king, having to show subservience or face death, I had to take racist ridicule from a professor who held the fate of my grade. In both events identity had to be arranged in order to make the fearful feel superior. I knew the drill, but I didn’t realize the dots connected back that far.

The pages were all done in pencil on prepared blue-line bristol comic paper. I tried to ink some of them. I stayed up late. I drank straight black coffee (I hated coffee). I was possessed. I had never been so proud of one of my pieces. I was curious as to what the group critique was going to say, especially the professor, who I felt needed the education. This piece was a labor of love, channeling a violent and emotional outrage into something coherent, concise and in sequential order! Despite my emotions I got lost in the art.

When it was my turn to workshop the class grew silent. The professor came to me, asked me what it was about and I told the story. One of my peers whose work and work ethic I really respected said slowly, “Ian, this is amazing” and I got other compliments like “This is your best work I have ever seen you do.” Even the teacher said it was good, except for one panel where he said he didn’t like the way I drew Lapu-Lapu because it made him look too much like Rocket Man (whatever that meant). Throughout the whole critique he couldn’t look me in the eye. To Mr. V.’s credit, although he never apologized I think he had second thoughts about his earlier racist comment. He gave me an A for the assignment and an A for a final grade. I think he learned something that day.

My favorite comment was less on the art and more on the content. It came from the best artist in the class; “Hey, Ian, did this really happen?”, I looked him straight in the eye and said, “Yeah.” And he nodded.

It was one of the most meaningful exchanges I’ve ever had in my life.

I remember weeks later watching a cheesy Filipino movie on the subject starring action star Efren Reyes. There was a scene where a Filipino woman successfully defends herself against a conquistador with less than pure intentions. The outcome was very gory. A fellow student said he was offended by the scene and found it racist against Europeans. I didn’t know what to say. Yeah it was gory, but did he want the antagonist to succeed? I’m sure he didn’t, he just wasn’t ready to acknowledge some of the ugly things that Europeans did to the “savage”. He wasn’t ready to have his colored glasses cracked–Meanwhile Mr. V, “the educated professor” had already cracked mine.

History has proven that the oppressor tries to control or change the identity of the oppressed to weaken them. The subterfuge helps prevent any threats of an uprising or stage in the status quo. They’ll ridicule that identity, change it, erase it or worse– become it (i.e. depicting Jesus as white and European looking). It’s a power manipulation technique, a sly method of bullying. In modern times, art and media is used to enforce this constantly. For example white actors are free to take major roles originally written for Asians, Native Americans, Persians or even Egyptians, while the actor of the designated race is only allowed to play the extra for background authenticity (The Last Airbender, Starship Troopers, 21, the Mummy Returns, Prince of Persia, Exodus: Gods and Kings). Meanwhile actors of other races are commonly not allowed to be the hero unless the role reinforces certain stereotypes. However they are allowed to be villains, exotic seductresses, side-kicks, roles that don’t threaten the status quo. How do we break this cycle of bad or lack of representation?

On that day I learned that we can resist this by creating our own story and art. Unfortunately our viewpoints are often hidden, however we have the power to — with laser focus — shine light into once hidden areas so that others can see the treasures that live there. Art is a reaction that takes a lot of self-control, but when that syzygy hits, it’s when you are truly let loosed. It is a more effective reaction than violence, with better results. It can contain your frustration, rage, and sadness and meld it into something worthwhile. Your suffering is not wasted nor without meaning. It can entertain and educate. It has become my chosen labor of love.

That was the day I found out that, with art you can be both the lover and the fighter. (I have come to believe that’s what love really is anyway). It had become my way not just to resist, but to make myself exist.

View the rest of Toledo’s “The Victor of Mactan.”

IAN E. TOLEDO is a writer, artist and teacher. He has a BA in Visual & Performing Arts from Syracuse University and an MA in Art & Art Education from Teachers College Columbia University. He is of Filipino descent, born in Connecticut and now resides in NYC.